Read more of UCS’s critical analysis of Oppenheimer and the global security issues it examines here.

In this opening stanza of one of my favorite poems, “La Jornada” by Antonia Quintana Pigno, the speaker laments the disastrous effects of J. Robert Oppenheimer’s love affair with New Mexico.

She suggests that her own love affair as a brown woman with the white scientist could have stopped the Manhattan Project and the development of the atomic bomb. This poem ran through my mind multiple times as I watched Christopher Nolan’s film Oppenheimer.

Like Nolan’s other films, the depiction of women in Oppenheimer is terrible. In this one, he manages to reduce two scientists—Jean Tatlock, a psychiatrist who was also queer, and Katherine “Kitty” Oppenheimer, a botanist—to a floozy and a drunk who are both in love with Oppie, not to mention that they are two of only four women with significant speaking parts. (The third is also involved in an extra-marital affair with Oppenheimer and the fourth was a Manhattan Project scientist who is depicted as trying to shut down the use of the bomb for war purposes. But I digress.) Quintana Pigno writes lovingly about her “Nuevo Méjico,” but it’s a different love than Oppenheimer had for New Mexico.

Oppenheimer

I could have loved you

wrapped my legs tightly

around your white buttocks

to keep you thinly against me

without desire

for food

for water from mountain streams

for the journey to Jornada del Muerto

for the creation of Trinity

“La Jornada” by Antonia Quintana Pigno

In the summer blockbuster, New Mexico serves as a desolate backdrop to Project Y and the Trinity test. The wind and rain that characterize the wild west that Oppenheimer and other Manhattan Project scientists must tame to build and test the bomb contradicts the querencia most of us have for our high desert homeland, the one that Quintana Pigno writes about. One of my favorite Oppenheimer quotes, which sits as an epigraph to “La Jornada,” features prominently in the film. The original quote, though, is different than the movie version. Oppenheimer once said, “My two great loves are physics and New Mexico. It’s a pity they can’t be combined.” In the film, Oppie says, “When I was a kid, I thought that if I could find a way to combine physics with New Mexico, my life would be perfect.” The truth is that his love for New Mexico, like his other romantic affairs, was disastrous. Who should really be pitied here? The truth is, Oppenheimer knew very little about people in New Mexico because he often went to New Mexico to be alone, that is, until he created a government project that changed the cultural and physical landscape of my ancestors forever.

Those left out of Oppenheimer

With the attention that the film has received, many people have been able to critique how the film leaves out entire populations of people, such as Indigenous communities, downwind communities, and Nuevomexicana/o farmers. It has allowed us to better explain to the world that New Mexico was not uninhabited in the 1940s. In fact, it has been inhabited since time immemorial. In a recent interview, I finally realized that the journalist was unaware of New Mexico’s geography, and I explained to her that Trinity and Los Alamos were 200 miles apart when I finally realized that she did not know this as she asked her questions. Yet another called it “Mexico” but then corrected herself and repeated “New Mexico.” Don’t get me wrong, I’m grateful that we have this chance to explain these things, and I don’t fault people for not knowing the geography of New Mexico. Certainly, the film makes no effort to distinguish the Pajarito Plateau (Los Alamos) from the Tularosa Basin (Trinity site); New Mexico is one amorphous, desolate desert in the film. Nevertheless, this portrayal is just another effect of nuclear colonialism.

After two bombs were used to attack Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, in August 1945, news of Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project broke worldwide. Oppie’s face appeared on the November 8, 1948, cover of TIME. As Hollywood magic would have it, Oppenheimer sees his reflection on the magazine cover as he walks into the Oval Office to meet with President Truman in the film. (Oppenheimer resigned from Los Alamos on October 16, 1945, but this inaccuracy with the TIME cover does not actually change much in the film.) It is during this scene that Truman asks Oppenheimer, “I hear you’re leaving Los Alamos. What should we do with it?” To which Oppenheimer responds, “Give it back to the Indians.” Not only is this comment ignorant, but it’s also racist. Oppenheimer and Groves knew who they displaced to institute Project Y; they just didn’t care. Nuevomexicanas/os and Indigenous people, in addition to the Los Alamos Ranch School, were dispossessed from their homes and homelands on the Pajarito Plateau. Not only did they not return the land, but the colonizers never left.

Dealing with the fallout

New Mexicans were left to contend with the lasting effects of the Manhattan Project, including intergenerational trauma, disease and death, contamination, secrecy and obscurity, and environmental racism. In Resolana: Emerging Chicano Dialogues on Community and Globalization by Miguel Montiel, Tomás Atencio, and E.A. “Tony” Mares, Atencio writes about Los Alamos and how northern New Mexico communities have resisted the effects of the Manhattan Project. Atencio writes, “Since the mid-1940s villagers had recognized the dangers of radiation, as men pushing wheelbarrows full of waste in the Los Alamos National Laboratories (LANL) suddenly turned ashen, went home, and died. In the villages, meanwhile, children were dying of leukemia. Despite the evidence from Los Alamos and the knowledge that chemicals, including commercial fertilizer, were polluting the land, we had been told that modern technology would improve nature” (Atencio 27). Stories of family members getting sick or dying because of their work at the Labs are no longer restricted to whispers at kitchen tables, and initiatives to keep traditional knowledge alive and in practice are thriving. Still, other northern New Mexicans, especially, are proud of the work they did and continue to do at the Labs. It’s a conundrum.

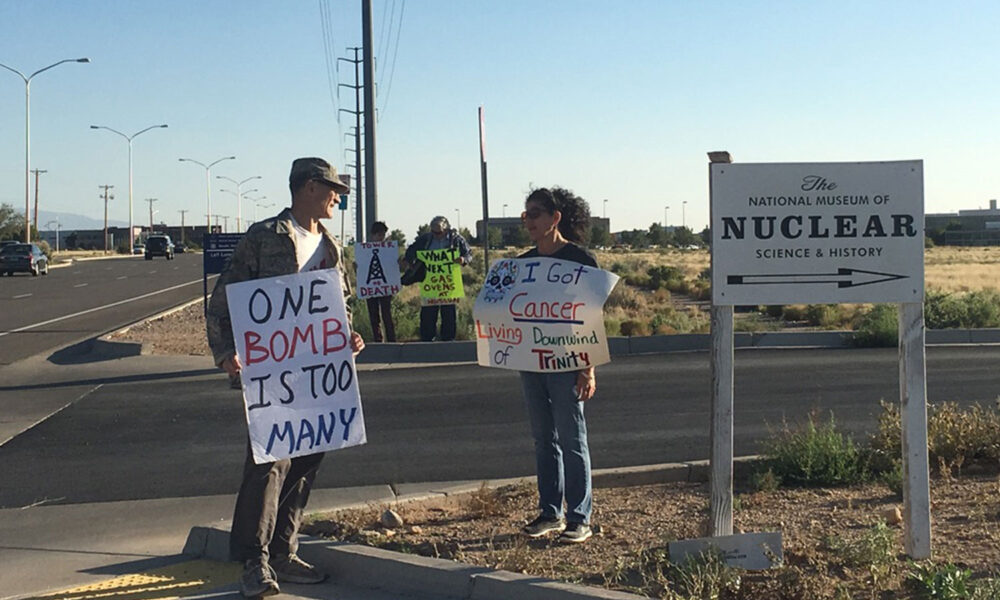

In southern New Mexico, the communities surrounding the Trinity site continue to deal with the legacy of illness and death created by the plutonium bomb called the Gadget. New research shows that fallout from the Trinity test reached forty-six states plus Canada and Mexico. A recent New York Times article quotes from the report that “locations in New Mexico where radionuclide deposition reached levels on par with Nevada” from atmospheric nuclear tests conducted at the Nevada Test Site. The new study offers support for the ongoing efforts to amend the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act to include the Trinity downwinders, who are not eligible under the current federal law. Since its establishment in 1990, the RECA fund has paid out over $2 billion; New Mexican downwinders have never been eligible for compensation under RECA.

Our own role in the current nuclear moment

Last week, the US Senate passed a bill to amend the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA). This new amendment would include not only New Mexico downwinders, but also it includes post-1971 uranium workers, other downwinders of the Nevada Test Site atmospheric nuclear tests, and downwinders in Guam from testing in and the Pacific Islands. The House must pass their version of this bill now, which is integral before RECA sunsets in 2024. People can call their US Representatives and ask them to support the RECA amendment.

But there is another conversation that has opened recently in New Mexico around the legacy of the nuclear industrial complex. In January 2022, the Archbishop of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, John C. Wester, released a Pastoral Letter, “Living in the Light of Christ’s Peace: A Conversation toward Nuclear Disarmament,” which actually calls for the abolition of nuclear weapons. Suddenly, there is a new conversation happening around the present-day role of nuclear science at the National Laboratories in New Mexico, namely Los Alamos. The National Nuclear Security Administration has tasked Los Alamos with producing a minimum of thirty new plutonium pits per year with a goal of eighty new pits per year between LANL and a second location – the Savannah River Site.

At the end of Oppenheimer, viewers are left questioning the guilt the film’s protagonist might have felt unleashing nuclear weapons into the world. But shouldn’t we also question what role the United States and other nuclear weapons-wielding counties have in the future of nuclear weapons? We must consider how future generations will look back on our nuclear policies and the choices we make. Are nuclear weapons and all their inherent risks and public health impacts a legacy that we really want to pass on?