By Jeremy Williams

“What comes into your mind when you think of environmental breakdown?” asks Laurie Parsons in the opening to his book Carbon Colonialism. For a lot of people it’s still melting ice and polar bears. If people feature, it’s likely to be forest fires or famines far away. With some notable exceptions, “what your example is unlikely to include is your own town, your own neighbourhood, your own street.” For readers in the west, the climate crisis is a step removed.

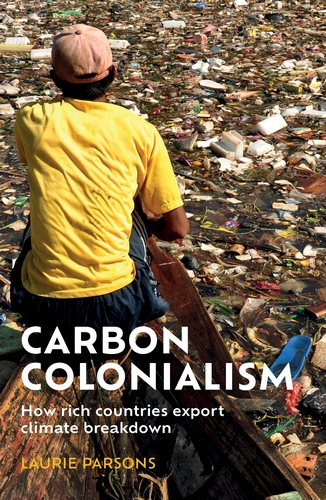

That is not the case everywhere, and it is not simply an accident of geography. As the book argues, environmental harm is often relocated rather than prevented. What is counted as environmental progress in one place can actually be just trade, with a country lowering its emissions by outsourcing production elsewhere. The result is a “system in which the environmental cost of wealth generation is paid in places far from where that wealth is accumulated.”

Parsons has seen this for himself, watching brick-makers in Cambodia firing their kilns with bags of discarded clothes from Western fashion brands, their children breathing in the toxic smoke. It’s a good example of how opaque and unaccountable global supply chains have become. No fashion brand would take responsibility for their clothes being burned in a brick kiln, and the chances are they don’t know it’s happening. Preventing it would be no easy task. It’s already illegal in Cambodia and it happens anyway.

Neither do we really know where those bricks will end up. They might be used in Cambodian cities, or they might be exported. Europe imports a growing number of bricks – which seems ridiculous when you consider how simple a brick is, and the vast emissions from shipping baked earth about the globe. But brick imports are rising in part because the rules about their production are so strict in places like the UK. The dirty business of brick-making hasn’t been reduced, but relocated. (See Parsons’ previous Blood Bricks project for more on this.)

This is a recurring theme in the book: “in many situations, problems are resolved by reducing their visibility rather than tackling them at root.” The world’s biggest consumers used to be producers too. That all changed with globalisation, which hid the environmental consequences of industry in other parts of the world. We just don’t know anything about our possessions and what it cost to produce them. There is no accountability, and “this ignorance is extremely lucrative.”

This outsourcing of environmental harm is true of plastic waste and ‘recycling’ dumped in developed countries. It’s true of electronic waste and discarded clothing. And it’s true of climate change too, with energy-intensive industry relocated to other countries, who are then blamed for not doing enough to reduce their emissions. If we were to take traded goods into account, the UK’s emissions would be 42% higher. (China’s would be 8% lower.)

For Parsons, all of this reflects a colonial mindset. Political independence doesn’t necessarily tell us much about where power really lies, and “frameworks that legitimate the exploitation of one environment for the benefit of another are colonial.”

Carbon Colonialism explains all of this very clearly, switching back and forth between on the ground reporting and wider theory. Parsons takes everyday objects – bricks, a pair of socks, teabags – and draws out lessons from their global supply chains. And it was great to hear more from Cambodia, a country we don’t hear from very much, and where Parsons has spent a lot of time.

Altogether, Carbon Colonialism is a stark reminder that for all its apparent environmental progress, consumer capitalism still relies on invisible ‘elsewheres’ to keep the economic wheels turning.

First published in The Earthbound Report.

Categories: book review, development, environment, resources, Reviews, social justice

2 replies »