Editor’s Note (8/21/23): On August 20 Russia’s space agency announced that a glitch had caused the Luna-25 spacecraft to crash into the moon, ending the mission.

Half a century after the cold war drove the Soviet Union to send a host of robots to the moon, Russia is attempting a lunar return amid high-stakes geopolitical maneuvering and a new international rush to the moon.

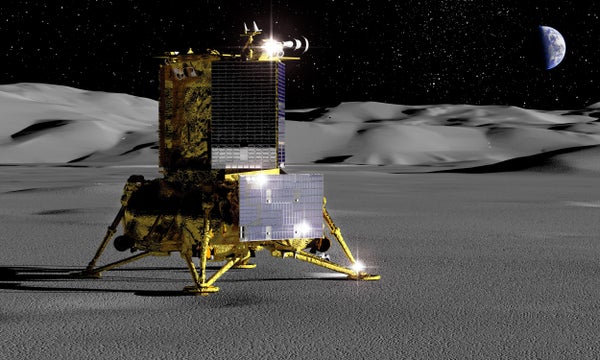

Luna-25, Russia’s first moon mission in nearly 50 years, launched on August 10 and is now orbiting the moon in preparation for touching down as early as August 21. Making a soft lunar landing is no easy feat, however, and experts say that Russia’s space program is now much weaker than it was in 1976, when Luna-24 fetched lunar rocks for scientists back on Earth to study.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“Obviously the Soviet Union and Russia have a very rich space exploration history, so they had, at one point in time, the technical ability, acumen and industry to be a great space power. But really since the end of the cold war and the fall of the Soviet Union, they’ve made a variety of decisions that have just completely undermined their infrastructure and ability to continue that great tradition,” says Bruce McClintock, a senior policy researcher at the RAND Corporation. Most recently, Russia’s invasion of neighboring Ukraine in February 2022 has drawn widespread international condemnation—and has led to associated harsh sanctions targeting the nation’s tech sector, which is crucial for developing and supporting space missions.

Leaders of Russia’s space agency, Roscosmos, first began planning the Luna-25 mission in the 1990s. Yet the spacecraft was slow to materialize because the nation prioritized crewed spaceflight and military efforts over science missions.

“Russia is seeking to restore its reputation domestically and internationally as a space science leader,” says Clay Moltz, a political scientist at the Naval Postgraduate School. “Due to funding gaps, Russia has not conducted any major deep-space missions in over a decade,” he adds. “Scientists within Roscosmos are seeking to prove that they can still conduct major space science missions in spite of sanctions and budget cuts.”

Now that Luna-25 has finally launched, it is bound for a landing site 620 kilometers from the lunar south pole, near Boguslawsky Crater, which is located about 70 degrees south of the moon’s equator. Previous Luna missions, as well as the crewed U.S. Apollo program and other lunar missions, have all clustered closer to the equator. The moon’s poles are a prized target today, however, because scientists have realized these regions hide water ice—an invaluable stockpile for life support or rocket fuel—in deep craters that never see the sun.

Boguslawsky Crater is too far removed from the lunar south pole to be considered truly “polar,” says Igor Mitrofanov, a planetary scientist at the Space Research Institute in Moscow. But it has sufficiently polarlike conditions for scientists to potentially see “something new” there as the lander studies the composition of the moon rock at and below the surface and scouts for evidence of water ice. Mitrofanov and his colleagues intend to use data and experience gained from Luna-25 to inform Luna-27 and Luna-28, which will both land closer to the south pole. The latter mission will even bring samples back to Earth.

The mission is scheduled to last at least one Earth year, although it may be extended if the spacecraft remains in good condition, Mitrofanov says. Luna-25 will sleep through the cold lunar night, which lasts about 14 Earth days, and operate only while the sun shines.

That’s a very different plan than Russia’s previous missions to the moon’s surface, which lasted about a week at most. “Practically all elements of basic technology are different, the scientific program is different, and actually, it is a mission of the 21st century,” Mitrofanov says.

Much like its Soviet-era predecessors, however, Luna-25 has been shaped by Russia’s situation on Earth. Not only have post-Soviet budget woes slowed the pace of lunar exploration dramatically in comparison with the rapid-fire launches of the 1960s and 1970s, but the geopolitics have changed, too.

During the cold war, the Soviet Union pushed its space program as a way of proving its superiority over the U.S. to countries around the world. That’s not how space exploration works anymore, says Svetla Ben-Itzhak, a political scientist at Johns Hopkins University, who works with the U.S. Space Force and the Department of Defense but offers her opinions as a private citizen.

“There are still firsts, but the question is: Who will actually stay and survive and establish a sustainable, persistent presence?” she says. “It is not just getting there; it is also staying and surviving, and this is not possible to accomplish alone.”

Luna-25 is a predominantly Russian mission because the country has struggled to retain partners. Although Japan and India considered partnering with Russia on the mission, both ultimately declined. The European Space Agency (ESA) had agreed to send a terrain camera called Pilot-D, which was meant to develop future pinpoint landing systems. Yet the ESA pulled the instrument shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and will be watching the touchdown attempt from the sidelines.

“I wish them all the best for a successful landing,” says Nico Dettmann, lunar exploration group leader at the ESA, who notes that the camera will fly next year on a mission run by the U.S. company Astrobotic. Although Mitrofanov says that the loss of the camera had “zero” impact on the Luna-25 mission, the end of European cooperation means that Russia will need to develop its own landing technology, as well as a drill, for the future Luna-27 mission.

And while China and Russia had in 2021 announced a joint lunar exploration program aimed at establishing a long-term crewed base at the moon’s south pole, China is now presenting that program as its own initiative, with contributions from many countries.

“It appears that [Russia] directly and adversely impacted the closest possible working relationship they had when it came to scientific exploration, and that was with China,” McClintock says. (Neither country is very forthcoming about its respective plans for space exploration, so it’s not clear whether China is distancing itself because of the war in Ukraine, the weaknesses of the Russian space program or other reasons entirely, he notes.)

Meanwhile India is also trekking to the moon as it attempts to become the fourth nation to accomplish a soft landing and join the former Soviet Union, the U.S. and China in that elite club. India previously attempted the feat in 2019 as part of its Chandrayaan-2 mission, but the lander crashed. Israel and Japan have also crashed lunar spacecraft during recent unsuccessful landing attempts. (The latter country’s craft was carrying a rover built by the United Arab Emirates.) Despite the flurry of failures, the momentum for a new “moon rush” is unflagging, with multiple nations and private companies all vying to send spacecraft there in coming years.

Now the world will be watching to see whether Luna-25 will join the ranks of operational lunar spacecraft or scatter debris across the barren surface. “The launch of Luna-25 was the ‘easy part,’” Moltz says. “The soft landing on the moon will be the real test.”