Around a third of human-generated greenhouse gas emissions comes from the global food system, and lost or wasted food is known to contribute some amount—but it has never been clear to exactly what degree. Now, by following specific foods through their entire life cycle, researchers have determined just how much this wasted food adds to emissions through phases such as harvest, transportation and disposal.

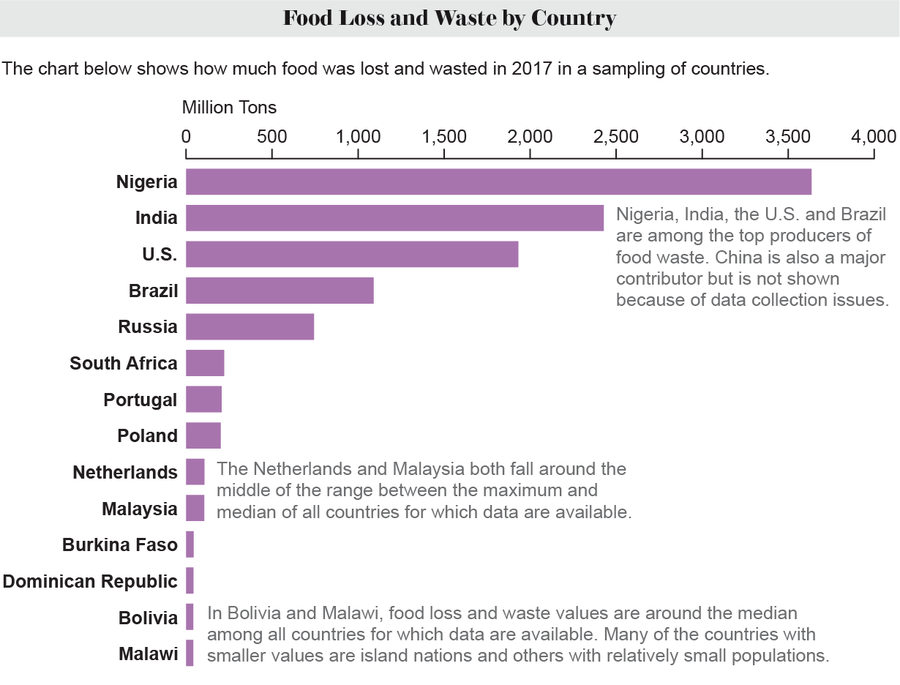

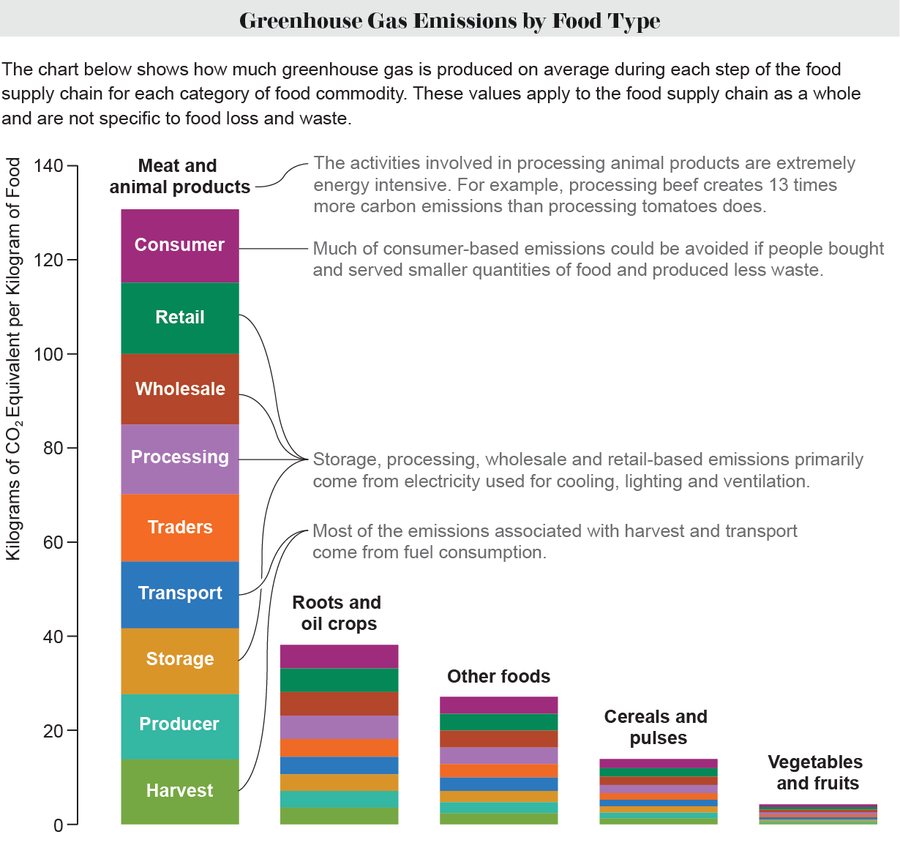

For a study in Nature Food, Xunchang Fei of Singapore's Nanyang Technological University and his colleagues used 164 countries' food supply data from 2001 to 2017 to estimate emissions across 54 food commodities and four categories: cereals and pulses; meat and animal products; vegetables and fruits; and root and oil crops.

Credit: Jade Khatib; Source: “Cradle-to-Grave Emissions from Food Loss and Waste Represent Half of Total Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Food Systems,” by Jingyu Zhu et al., in Nature Food, Vol. 4; March 2023 (data)

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Roughly a third of food is lost during harvest, storage and transportation or is wasted by consumers. The team found this food was responsible for greenhouse gases equivalent to 9.3 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide—about half the global food system's total emissions—in 2017. Four countries (China, the U.S., India and Brazil) contributed 44.3 percent, mainly owing to their dietary habits and large populations. Of the four food categories, meat and animal products were the source of almost three quarters of emissions that occurred during the supply-chain phase for food that was ultimately lost.

The study considered emissions across nine postfarming stages, which vary among regions—for instance, developed countries' advanced waste-treatment technologies can create fewer emissions. Such intricate details show how “different countries should set different targets for [food loss and waste] reductions,” Fei says—such as reducing meat production in some areas, and switching from landfills to anaerobic digestion or composting processes in others.

Credit: Jade Khatib; Source: “Cradle-to-Grave Emissions from Food Loss and Waste Represent Half of Total Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Food Systems,” by Jingyu Zhu et al., in Nature Food, Vol. 4; March 2023 (data)

Food systems expert Prajal Pradhan of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany notes that the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals aim to halve food waste in the coming years—which Pradhan says wouldn't be enough to limit global warming but would be a start. Based on this study, he says, emissions could decrease if “high-income countries could focus on saving food discarded by consumers, and low- and middle-income countries could prioritize avoiding food loss during harvesting, processing, storage and transport.”