- Science News

- Frontiers news

- Asha de Vos – Every coastline needs a local hero

Asha de Vos – Every coastline needs a local hero

Author: Thimedi Hetti

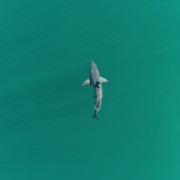

In the world of marine science, Dr. Asha de Vos rarely needs an introduction. The Sri Lankan marine biologist and ocean educator is best known for her pioneering work on blue whales and for founding the non-profit Oceanswell, Sri Lanka's first marine conservation research and education organization. Its flagship project, the Sri Lankan Blue Whale Project, is the longest running blue whale project in the northern Indian ocean. With a seemingly never-ending list of accolades and achievements, including being named one of BBC’s 100 Most Influential Women in 2018, Young Global Leader by the World Economic Forum, TED Senior Fellow and National Geographic Explorer, I felt honored to have had the chance to speak to a true trailblazer and someone I have looked up to for years.

Photo Credit: Prishan Pandithage

Speaking from her home in Sri Lanka, Dr. de Vos covered everything from her research and work, to being a woman in science and raising awareness on the issue of parachute science. She described in detail the different projects and studies lead at Oceanswell, looking at the impact of the whale watching industry and COVID-19 lockdowns on small scale fisheries among other studies such as beach strandings, which involves the contribution of volunteers and members of the public.

“My passion is about research that feeds into conservation so that we can have real change on the ground. I want people to have a collective understanding of what’s out there and want them to feel like they can be scientists too. My aim is to create a community of ocean-conscious individuals. We typically and traditionally see the ocean as a place of extraction and not a place of interaction. So I want to change that and I want people to have a better understanding and to also have fun doing it.”

I wanted to know more about her upbringing, and whether she had any influences from women in science. “Unfortunately, not. I grew up in a time where there was no internet, and we were dependent on encyclopaedias and The National Geographic magazines. People I saw in the magazines didn’t represent me in any way, there certainly weren’t people of colour and there were very few women. Luckily for me that wasn’t a turn-off. The advantage I had was the support of my parents who were my role models and always followed the motto ‘do what you love and you’ll do it well’. My mother said to me at a young age, ‘If we can afford to educate one of you when you grow up (I have one older brother), it will be you, because he’s a boy and the system is already set up for boys, but for a woman, it’s much more difficult.’ It was really powerful, there was this really focused desire to ensure that I had my own life, independence and my own path, coming from a culture which doesn’t always look at their girl children like that.”

Expanding on the systemic sexism she faced growing up in Sri Lanka, Dr. de Vos reflected on her experiences as a woman in science, **“**People tend to listen more if you’re a man in government, regardless of whether they’re saying something accurate or not. In a country and patriarchal society like Sri Lanka, there are definite challenges for women but I’m just going to keep dealing with these challenges. When I was working in an international conservation agency, I would go for government meetings where I was the only person with the knowledge that I had, and people would start talking amongst themselves because I was too young and too female for them. I remember being really frustrated, and it can really turn people off. But luckily my advantage is that I was so stubborn and I’ve stuck around for so long that now they have no choice but to ask me to come to meetings, or to ask for my opinion. Unfortunately, we live in a world where if you’re a woman, you have to work harder, but at this point in time, I tell people to work so hard that they stop seeing you for your gender/age, and instead as the most qualified person in the room.”

Moving on to the subject of parachute science, something Dr. de Vos advocates strongly against, she emphasized the importance of raising awareness around this issue. **“**Parachute science is when predominantly Western researchers come into countries with conservation issues like Sri Lanka, collect and publish all this data and thus propel their careers. But there’s a big gaping void because they haven’t engaged with or acknowledged the contributions of the local researchers. It really serves just one person, it doesn’t serve people on the ground and can cripple existing conservation efforts. There are people on the ground working on a problem, trying to be sensitive, understanding the political situation and local context, and foreign researchers swoop in and out, make their assumptions and ultimately advance their own careers.”

It is a huge problem which Dr. de Vos faced personally. From the very early days, she was told that her discovery (on Sri Lankan blue whale poo) was amazing but it could be more amazing if a foreign researcher came and did the research. “The Sri Lankan Blue Whale Project was my eureka moment, it’s a long term project that has created opportunities for people locally, we’ve been able to work with the whale-watching industry and share what we are learning with them. Protection of species is a long-term effort, it’s not a flash in the pan, it takes a lot of persistence and time.”

“With our projects, we welcome collaboration, I totally accept there is so much expertise and skill outside Sri Lanka and I myself have so much to learn. But I work with people who want to actually make a change rather than being the face or first author of the project. As I say ‘every coastline needs a local hero’, and that’s the only way we’re going to make a change. Talent is equally available but opportunity isn’t, and our job is to create the opportunities.”

On top of the numerous awards and accolades Dr. de Vos has received over the years for her work and leadership in the field, she has made many television appearances including David Attenborough’s A Perfect Planet and National Geographic’s Secrets of the Whales. **“**Life is a marathon, it’s not a sprint, and these awards are like the high fives along the way. It’s really nice to be recognised and acknowledged for what you’ve done, but you can’t stop each time you win an award. Those are all real moments of pride and I am very grateful for these opportunities. When I started out, I was a kid with a dream and supportive parents, those were the only ingredients I had. So I want people to see that it’s achievable. I have always lead with my science, with the things I am passionate about. I work very hard behind the scenes to make sure that the messages I’m putting out there are absolutely steeped in fact, clear and digestible. I think I’ve had the opportunities to appear on these platforms because I work so hard.”

Coming from Sri Lanka myself, I have seen first-hand how rare the conversations are on studying marine biology/conservation in a country that, ironically, is surrounded by ocean. I wanted to ask about the importance of getting the younger generation involved in marine science. “The ocean is 70% of our planet: we need more people working together on behalf of the oceans. I don’t want the younger generation to just inherit a planet that’s broken, I want us all working alongside each other so we can all start to make the change that they want to see for their futures.”

In conclusion of our conversation, we spoke about the future. “I want to be able to write myself out of a job by making sure we’ve brought on enough people that are all engaged and excited about working for the oceans. My goal is to try to solve these world problems, but fundamentally that’s not going to happen unless we have that next generation of amazing, diverse, ocean heroes from all backgrounds working for the oceans.”

Frontiers is a signatory of the United Nations Publishers COMPACT. This interview has been published in support of United Nations Sustainable Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.