For many families, extended relatives are a core part of caregiving. Grandparents, aunts and uncles can help parents look after young children. In turn, siblings and cousins may help care for aging parents. But the availability of such support—which many cultures have depended on for millennia—is quickly dwindling: a new study predicts extended families around the world will keep getting smaller as people live longer and have fewer children.

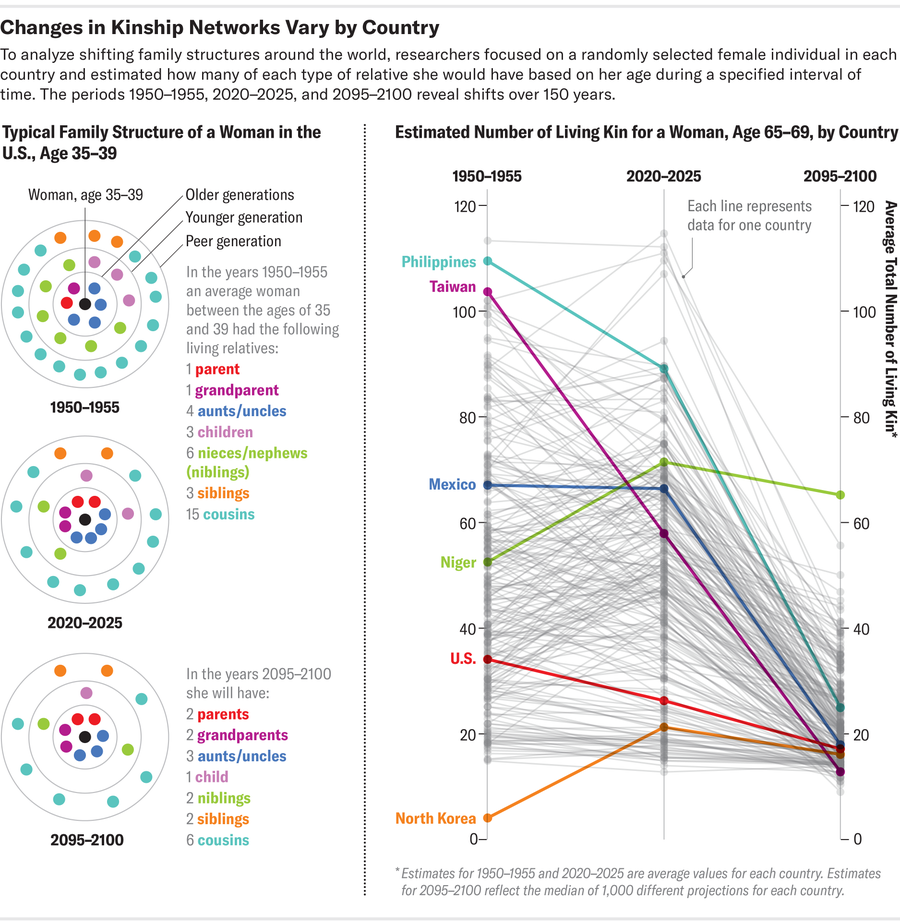

Using international demographic data, researchers recently projected the structure of families in every country around the world. They estimated that, globally, a woman who is 65 years old in 2095 will have only 25 living relatives. That represents a nearly two-fifths reduction from an estimated total of 41 relatives in 1950—and a nearly 42 percent reduction from an estimated total of about 43 relatives in 2023, according to the researchers. These estimates suggest that more people, especially in lower-income countries, will face a steadily increasing burden of caring for older people and children as intergenerational support disappears. The findings, which also note a pressing need for more formal care systems or institutions, were published in December in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Understanding changing family structures is an urgent matter in many countries that lack effective social security or other institutional support systems, says Sha Jiang, a demographer at the University of California, Berkeley, who was not involved in the study. Instead societies often have to rely on families to support the most vulnerable people in their population, such as older people. “So this raises an important issue,” Jiang says. “Will there be enough family members to take care of those [older people]? Or do we put too much burden at the family level?”

Researchers can analyze long-term data trends to answer these questions. Demographers look particularly at a phenomenon called the demographic transition: a shift away from high birth and death rates. Many analyses show this is currently causing the world’s population to skew older. But how this change specifically affects extended families and their composition has received less attention, says the new study’s lead author Diego Alburez-Gutierrez, a social scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Rostock, Germany.

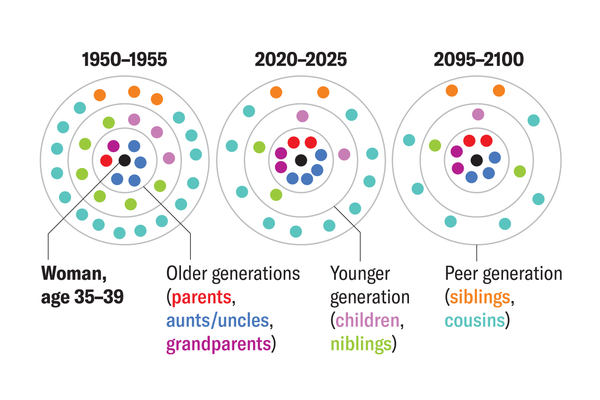

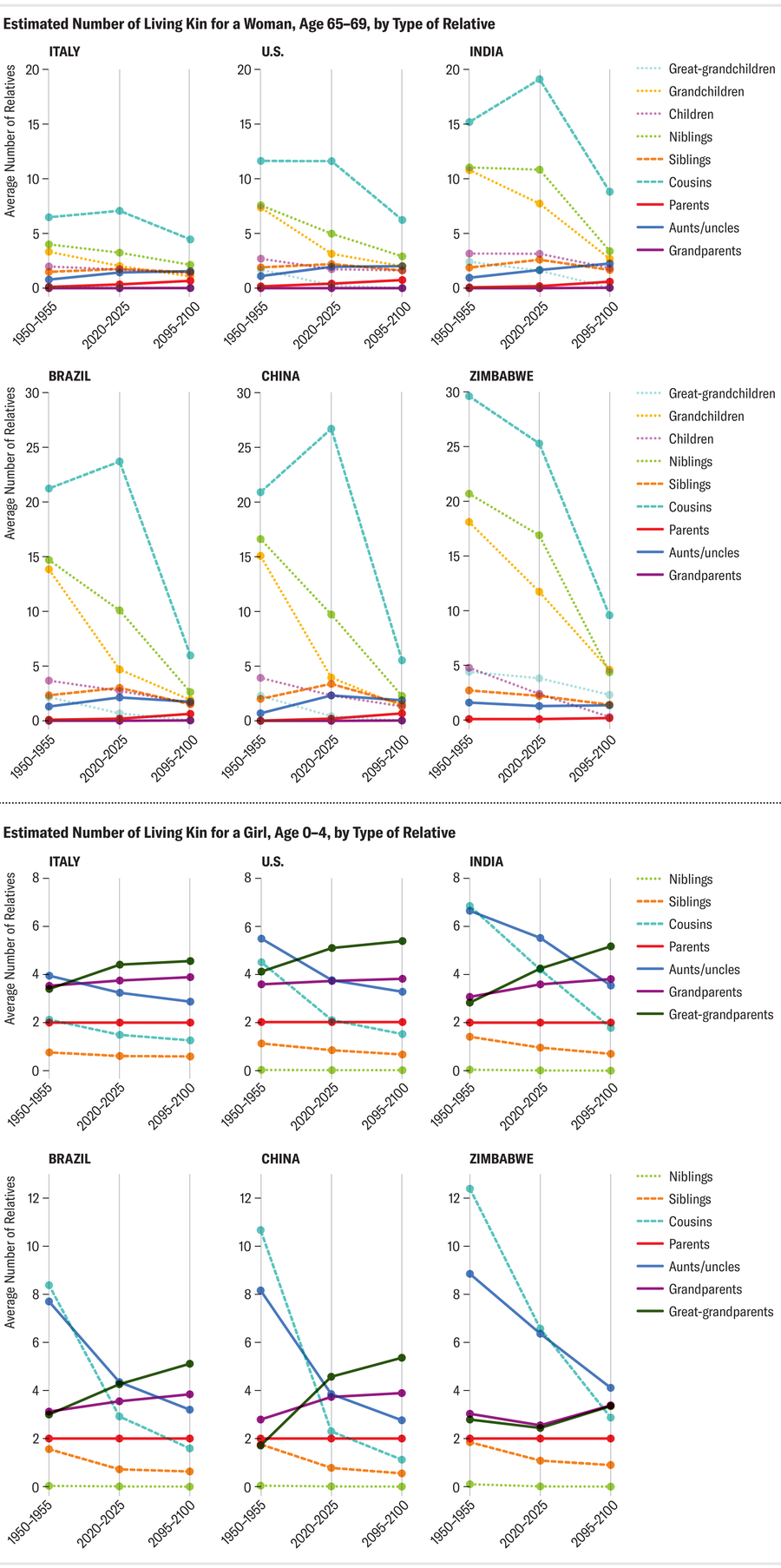

In their analysis, Alburez-Gutierrez and his colleagues made three major predictions about family structures, also called kinship networks. First, extended family size will likely decrease over time. Second, the composition of families will narrow: Alburez-Gutierrez explains that people will have fewer close-aged relatives in their own generation, such as siblings and cousins, and more ancestors, such as grandparents and great-grandparents. Third, age gaps between generations will grow as people increasingly have children later in life.

Forecasting patterns like this on a global scale “wouldn’t have been possible five years ago,” says Ashton Verdery, a Pennsylvania State University sociologist and demographer, who was not involved in the study. Many past demographic studies have focused on the nuclear family (defined as two parents and their children) because most readily available data measure changes within individual households. Methods that quantify changes in the number of cousins, aunts, uncles, niblings (a term for nieces and nephews) and other extended family greatly advanced in the past decade. “It’s a fantastic application of newly developed methods,” Verdery says.

The study foreshadows potentially drastic problems for health care. The findings suggest extended families may shrink very quickly in countries that are just beginning to see lower birth and death rates, such as those in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa. Most of these countries currently don’t have systems in place to care for a growing aging population and will likely struggle with the rapid change, Alburez-Gutierrez says. Much more of the medical, financial and emotional burden may fall on a single person instead of being spread out over multiple family members. This would put additional stress on those who are lower-income and stretched for time.

Some countries that already have low birth and death rates are facing these issues today. In China familial-based care is still considered the norm, Verdery says. But as the country undergoes mass aging, and the availability of caregivers dwindles there, people are often “sandwiched” between taking care of their kids, as well as their own parents and grandparents. Some face increasing financial stress as they pay for older adults’ care, in addition to supporting their own children. Others, notably many women, often drop out of the labor force to invest more time in caring for their family, Verdery says. Smaller extended families also mean some members may become increasingly isolated socially and could struggle with loneliness.

Alburez-Gutierrez notes that this new analysis does not include adoptive families and LGBTQ+ families. “People can make a family in many other ways,” he says. But current data and modeling tools are limited in their ability to quantify these family networks, as well as other sources of support, such as friends or other community members.

Strategies that address an aging population also may be useful when it comes to supporting smaller families, Alburez-Gutierrez adds. These might include extending health care coverage for aging adults, restructuring pension systems and investing in affordable child care infrastructure. Initiatives in some countries are also building more multigenerational housing to make it easier for older adults to live with their children, Verdery says. Other countries have found creative ways of using existing community structures to foster social connectedness. France, for example, launched a program a few years ago where postal workers can make check-ins on older residents as they deliver mail along their routes. Community support organizations can also help adults navigate difficult logistical, financial and emotional challenges of long-term care.

Families are very relevant when it comes to understanding population health, especially outside the Global North, Alburez-Gutierrez says. Societies have been built around the expectation that supportive family networks will always exist, he says, “but that is going to change in the near future.”