As this past October came to a close, it marked the hottest 12-month period ever recorded, a new analysis finds.

This stark milestone is the latest in a string of superlatives to emerge this year that show how much carbon pollution has warmed the planet—and how that trend is accelerating. It also comes just weeks before international negotiators are set to meet and hash out issues around achieving the Paris climate accord’s fundamental goal: limiting global warming to no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial temperatures.

Nonprofit organization Climate Central crunched international data and calculated that from November 2022 to October 2023, Earth’s temperature was 1.3 degrees C (2.3 degrees F) above preindustrial levels, a sign of how close the world is to missing that goal and experiencing ever worsening impacts of climate change.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“This is the hottest temperature that our planet has experienced in something like 125,000 years,” said Andrew Pershing, Climate Central’s vice president for science, during a press briefing on Wednesday. He later added that “this is not normal. These are temperatures that we should not be experiencing. We’re only experiencing them because we put in too much carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.”

In addition to the 12-month record this year, this Juy was the hottest month ever, and this September was the most anomalously hot month, meaning its temperature was the highest above the long-term average. The latter was so much hotter than the previous hottest September that in a recent post on X (formerly Twitter), climate scientist Zeke Hausfather called it “absolutely gobsmackingly bananas.”

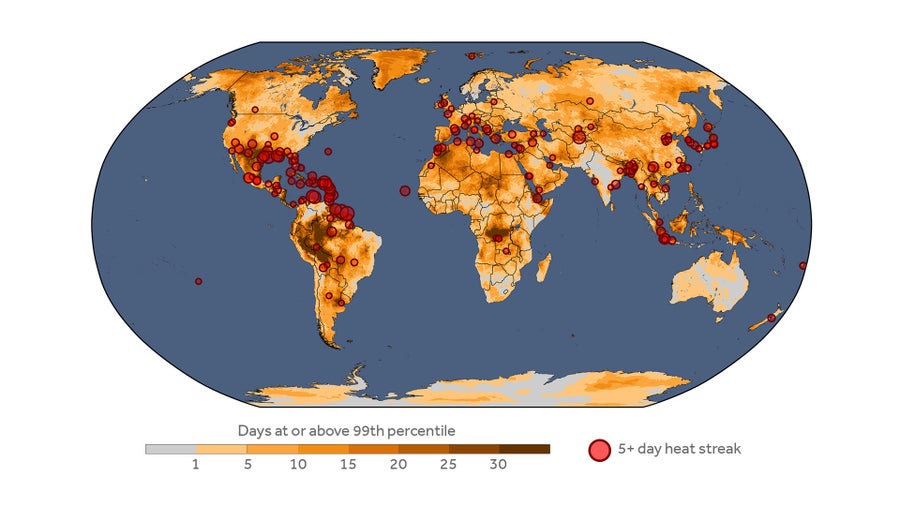

The number of days with locally extreme temperatures (redder colors correspond to more days of extreme heat). The circles indicate cities with at least one streak of 5 or more days of extreme temperatures that is attributable to climate change. The size of the circles reflects the length of the longest heat streak. Credit: Climate Central

But Pershing noted during the press briefing that people don’t experience the global mean temperature. “We experience our daily weather.... That’s how climate change impacts us,” he said.

To help people understand that connection, the Climate Central researchers looked at the fingerprints of climate change on daily temperatures around the world. They calculated that 5.8 billion people felt at least 30 days of above-average temperatures that were made at least three times more likely because of climate change. That included nearly everyone in Japan, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Egypt, Ethiopia, Italy, France, Brazil, Mexico, and all of the Caribbean and Central America.

The Climate Central researchers also found that about 500 million people in 200 large cities experienced at least five days of heat that ranked in the highest 1 percent of temperatures for each city. Among cities of at least one million people, Houston had by far the most such days in a row, with 22. New Orleans and two cities in Indonesia—Jakarta and Tangerang—each had 17 such consecutive days. Each of those heat streaks was made at least five times more likely by global warming. In all, 144 cities had periods of hot temperatures that were made at least twice as likely by climate change.

Attribution studies performed by other scientists have shown that the heat waves that plagued the U.S. Southwest and Europe over the summer would have been “virtually impossible” without climate change. Similarly, summerlike temperatures that hit South America during the Southern Hemisphere’s winter were 100 times more likely because of it.

“The whole point of this attribution science is to make the connection between what people are experiencing and climate change,” Pershing said. “These impacts are only going to grow as long as we continue to burn coal, oil and natural gas.”

Extreme heat poses a serious threat to human health, especially among the very old, the very young and low-income communities who may not have access to air-conditioning. Though populations in developing countries experience a much higher burden of these conditions, even wealthy nations such as the U.S. and many European countries felt the impact this year. In Europe, “we saw something close to COVID-era stretching of hospital facilities,” said Joyce Kimutai of the Kenya Meteorological Department during the briefing. Kimutai was not involved with the Climate Central analysis but does attribution work with the World Weather Attribution (WWA) team, an international group that co-developed methodology used in the report and co-hosted the press briefing.

The bulk of this year’s exceptional global heat has been linked to climate change, but there has also been a very small boost from an El Niño event. El Niño is a natural climate cycle that periodically features hotter-than-normal waters in the eastern part of the tropical Pacific Ocean. The ocean releases that heat into the atmosphere, both warming the planet and triggering a cascade of changes in atmospheric circulation patterns. That, in turn, affects weather around the world.

Chances are good that 2023 will be the hottest official calendar year on record, overtaking 2016 (and 2020, which some climate-monitoring agencies found to be tied with 2016). It could also be the first individual year for the entire Earth to be more than 1.5 degrees C hotter than preindustrial levels. (Individual months have already crossed that mark.) And 2024 is expected to be just as hot or even hotter, because El Niño typically peaks during the Northern Hemisphere’s winter, and its effects on global temperature lag that peak by a couple of months. “We’re going to continue to set these records as we move on into next year,” Pershing said.

Even if the planet crosses that threshold this year or next, there is still some time—though it is fast dwindling—to reach the Paris accord goal, which considers temperatures over an average of many years, not a single one. WWA co-leader Friederike Otto, a climate scientist at Imperial College London’s Grantham Institute for Climate Change and the Environment, emphasized during the press briefing that achieving the 1.5-degree-C goal is physically achievable. The main impediments, she said, have all been a matter of political will. Otto, who was not involved in the Climate Central analysis),and the other speakers said this was a crucial point heading into the upcoming 28th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, or COP28, which will be held from November 30 to December 12 in Dubai.

“What will really, really, really be important for the discussions going into this COP is phasing out fossil fuels” Kimutai said. “We clearly see that as we continue to burn these fossil fuels, temperatures will definitely continue rising—and we are seeing these impacts are continuing to accelerate.”

If we don’t rein in emissions, 2023 “will be a very cool year soon,” Otto said. “When we stop burning fossil fuels,” she added, “global temperatures will stop rising, which means that heat waves will stop getting worse,” which is “the really good news.”