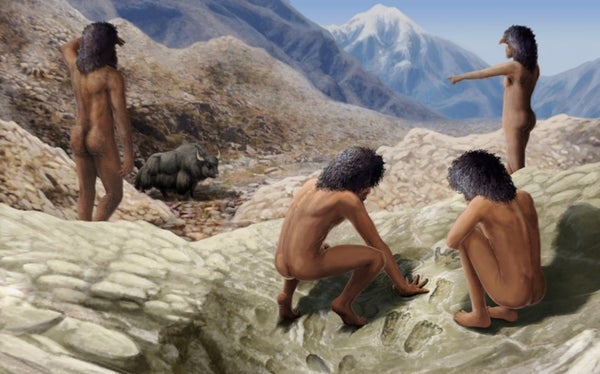

About 200,000 years ago, ice age children squished their hands and feet into sticky mud thousands of feet above sea level on the Tibetan Plateau. These impressions, now preserved in limestone, provide some of the earliest evidence of human ancestors inhabiting the area and may represent the oldest art of their kind ever discovered.

In a new report, published Sept. 10 in the journal Science Bulletin, the study authors argue that the hand and footprints should be considered "parietal" art, meaning prehistoric art that cannot be moved from place-to-place; this usually refers to petroglyphs and paintings on cave walls, for instance. However, not all archaeologists would agree that the newfound prints meet the definition of parietal art, an expert told Live Science.

Traces left by ice age children

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Study author David Zhang, a professor of geography at Guangzhou University in China, first spotted the five handprints and five footprints on an expedition to a fossil hot spring at Quesang, located more than 13,100 feet (4,000 meters) above sea level on the Tibetan Plateau. The authors dated the sample by assessing how much uranium, a radioactive element found naturally in the environment, could be found in the prints. Based on the rate at which uranium decays, they estimated that the impressions were left about 169,000 to 226,000 years ago — smack dab in the middle of the Pleistocene epoch, which occurred 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago.

And judging by the size of the prints, the team determined that the marks were left by two children, one about the size of a modern-day 7-year-old and the other the size of a 12-year-old. That said, the team can't be sure what species of archaic humans left the prints, said study co-author Matthew Bennett, a professor of environmental and geographical sciences at Bournemouth University in Poole, England.

"Denisovans are a real possibility," but Homo erectus was also known to inhabit the region, Bennett told Live Science, referring to a couple of known human ancestors. "There's lots of contenders, but no, we don't really know."

The prints supply the earliest evidence of hominins at Quesang, "but there is growing evidence of archaic humans being around the Tibetan Plateau at a similar time," Bennett added. For example, scientists recently recovered a Denisovan jawbone in the Baishiya Cave, located at the northeastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau, said Emmanuelle Honoré, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Université Libre de Bruxelles in Belgium, who was not involved in the study. The mandible is "at least" 160,000 years old, researchers reported in 2019 in the journal Nature, meaning the bone remnants could date back to the same period as the Quesang handprints, Honoré told Live Science in an email.

That said, the Baishiya Cave lies many miles north of Quesang and sits at only 10,500 feet (3,200 m) above sea level, so the newfound handprints supply the oldest evidence of occupation in the central, highest-elevation region of the plateau, said Michael Meyer, an assistant professor of geology at the University of Innsbruck in Austria, who was not involved in the study. Like the study authors, Meyer suspects that Denisovans likely left the handprints, so "the study could thus indicate that Denisovans were the first Tibetans and that they originally adapted genetically to cope with the high-elevation stress," he told Live Science in an email.

The handprints themselves are made of travertine, a kind of freshwater limestone formed by mineral deposits from natural springs. When first deposited, travertine forms a "very fine, sludgy mud," which one can easily push their hands and feet into, Bennett said. Then, when cut off from water, the travertine hardens into stone.

On a previous expedition, conducted in the 1980s, Zhang uncovered similar hand and footprints near a modern hot spring bathhouse at Quesang, and in general, many traces of early humans can be found adorning the slopes nearby. Those previously uncovered hand and foot impressions vary in size, implying that they were left by children and adults, but they appear to have been made organically as people made their way over the land. The newfound prints, on the other hand, differ in that they appear to have been left deliberately, Bennett said.

"They're deliberately placed ... you wouldn't necessarily get these traces if you were doing normal activities across the slope," he said. "They're actually positioned within the space, as if somebody was, you know, making a more deliberate composition." Bennett compared the prints to finger flutings — a kind of prehistoric art made by people running their fingers over soft surfaces on cave walls. Both children and adults are thought to have participated in finger fluting, and similarly, Bennett said that the Quesang prints should also be considered art.

To draw a comparison to modern times, "I've got a 3-year-old daughter, and when she does a scribble, I put it on the fridge ... and say it's art," Bennett said. "I'm sure that an art critic wouldn't necessarily define my child's scribbles as art, but in general usage, we would do [so]. And this is no different."

Work of art?

If the Quesang prints qualify as parietal art, they would be the oldest known example of the genre yet discovered, the authors noted in their report. Previously, the oldest known examples of parietal art were hand motifs and hand stencils found on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi and in the El Castillo cave in Spain, which both date between about 45,000 and 40,000 years old.

However, "Quesang has little to do with those two sites, except for the fact that they are all three displaying hand [and] footprints," Honoré told Live Science. "Leaving a print in the mud or doing a stencil print with pigments is a really different process, not only from a technical point of view, but also from a conceptual point of view."

For Honoré, personally, parietal art includes paintings and engravings made on rock, but would exclude markings like finger fluting or the Quesang prints, and some other archaeologists hold the same view. "Regarding finger fluting, some authors consider it already as art, others as precursors of art, others as 'experiment [or] play' rather than art," Honoré said. "I would personally be among this last category of researchers."

"Classifying these human traces as art is something that is of only secondary importance, in my opinion," Meyer said. The most interesting implications of the new study are that human ancestors occupied the high Tibetan Plateau much earlier than previously thought, and that raises questions about which species of hominin left the prints and how they first arrived to the plateau. Looking forward, Meyer said he hopes there will be further studies to verify the age of the imprints and clarify how they remained so well preserved over time.

Regardless of how contemporary scholars define the prints, it's important to note that "what we define as art was probably not viewed with the same eye by the people who made it," Honoré said. So we may never know what those ancient hominin children were really up to when they pressed their hands and feet into the hillside, or what their older kin might have made of their efforts. For Bennett, though, the fossilized traces of two children playing in the mud still count as art in his book.

Copyright 2021 LiveScience, a Future company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.