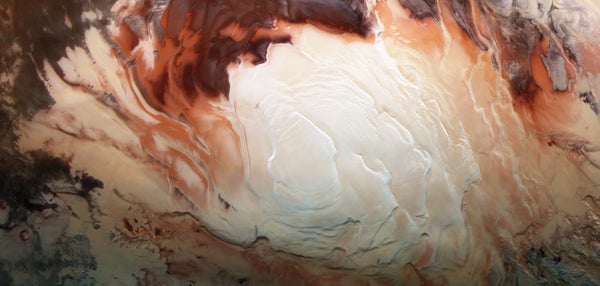

Bright reflections that radar detected beneath the south pole of Mars may not be underground lakes as previously thought but deposits of clay instead, a new study finds.

For decades, scientists have suspected that water lurks below the polar ice caps of Mars, just as it does here on Earth. In 2018, researchers using the MARSIS radar sounder instrument on the European Space Agency’s Mars Express spacecraft detected evidence for a lake hidden beneath the Red Planet’s south polar ice cap, and in 2020, they found signs of a number of super-salty lakes there. If these lakes were remnants of water that was once on the surface, these reservoirs may have once harbored life and may still, the scientists noted.

However, in order to form and maintain liquid water at this spot on Mars, an implausible amount of heat and salt may be needed, given what is currently known about the Red Planet, according to the lead author of the new study, Isaac Smith, a planetary scientist at York University in Toronto, and his colleagues.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

York and his team say that clay minerals known to exist in the south polar region of Mars can explain these radar reflections without invoking lakes of water.

“Among the Mars community, there has been skepticism about the lake interpretation, but no one had offered a really plausible alternative,” Smith told Space.com. “So it’s exciting to be able to demonstrate that something else can explain the radar observations and to demonstrate that the material is present where it would need to be. I love solving puzzles, and Mars has an infinite number of puzzles.”

The scientists focused on minerals known as smectites, a kind of clay whose chemical composition is closer to volcanic rock than to other types of clay. Smectites form when eroded volcanic rocks undergo mild chemical changes after interacting with water. These clays can hold large amounts of water, they noted.

Smectites are extremely abundant on Mars, concentrated mostly in its southern highlands. “On Earth, they’re commonly found near volcanoes in Alaska or Central America, but can be found on every continent,” Smith said.

In the lab, the researchers cooled smectites to minus 45 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 43 degrees Celsius), the kind of cold one might find on Mars. They found that water-laden smectites could generate the kind of bright radar reflections detected by MARSIS (short for “Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionospheric Sounding”), even when mixed with other materials.

When Smith and his colleagues analyzed previous visible and near-infrared data collected from Mars’ south pole, they also found evidence of smectites there. They suggested that smectites formed at Mars’ south pole during warm spells, when the area was covered by water. These water-loaded clays were later buried under water ice.

“Looking backwards in time, to when Mars was much wetter, this supports evidence that liquid water was present over a larger area than we anticipated,” Smith said. “Because these clays are at and beneath the south polar cap, it must have been warm enough there long ago to support liquids.”

All in all, the researchers suggested that smectites are a more viable explanation for the bright radar reflections seen there instead of super-salty lakes.

“Science is a process, and scientists are always working towards the truth,” Smith said. “Showing that another material besides liquid water can make the radar observations doesn’t mean that it was wrong to publish the first results in 2018. That gave a lot of people ideas for new experiments, modeling and observations. Those ideas will translate to other investigations of Mars and already are for my team.”

In the future, “I would like to repeat the measurements at even colder temperatures and with a more diverse set of clays,” Smith said. “There are other types of clays found on Mars that I suspect can also make these reflections, and it would be good to follow up with them.”

The scientists detailed their findings today (July 29) in the journal Geophysical Review Letters.

Copyright 2021 Space.com, a Future company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.