Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the oldest and deadliest diseases that can now be prevented and cured. Many researchers worked to develop effective TB treatments, but they didn’t do it alone. In The Black Angels: The Untold Story of the Nurses Who Helped Cure Tuberculosis, author Maria Smilios chronicles the lives and lifesaving work of the Black nurses of Sea View Hospital on Staten Island, N.Y., who worked alongside them and were largely unknown to history until now.

Caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis, TB is a terrifying illness that is currently the second-deadliest infection globally, behind COVID. It easily infects a host as an airborne germ and lies dormant until it jumps to attention, when it can quickly liquify the lungs, wilt the skin or even swell one’s tongue beyond their mouth. For generations, tuberculosis was a death sentence, and in some developing countries, it still is. Recently TB medication became more widely available when Johnson & Johnson lowered the drug price after John Green, a young adult novelist and YouTube star, called the company out online as part of a long public campaign.

Scientific American spoke with Smilios about her new book and the Black nurses who saved so many lives in their wards and across the world while risking their own lives along the way.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Credit: Penguin Random House

You follow so many interesting characters in this book. Initially we see the world through the eyes of Edna Sutton, the aunt of Virginia Allen. (Both women were nurses at Sea View.) But there are many other characters that have stories—doctors, patients and even some of the living relatives of the Sea View nurses. How did you decide which characters to unfold this kind of complicated story around?

It was hard. I knew I had to make Edward Robitzek [who helped lead the development of isoniazid, an antibiotic to treat TB] a main character in the sense that he’s the one who initiates these [drug] trials. None of this would have happened if it wasn’t for him, and he said that none of it would have happened if it wasn’t for the nurses. I also knew that I had to have the patients in there; I was able to locate two of them who were still alive. I needed to focus on some of the more prominent trial patients that were featured in newspapers, such as Hilda [Ali]. Then I was really drawn to the Black nurse Missouria [Meadows-Walker]’s story. She had to be a prominent figure because she stood her ground. So much change happened because of her. The same thing happened with Edna. She was one of the first Black people to own a home in that part of Staten Island, and she was basically the cornerstone for an entire new Black community in Staten Island that’s still there and still thriving.

You mention Virginia Allen and Bernice Alleyne [a relative of Missouria Meadows-Walker] in your acknowledgements. Could you tell me about your relationship to them and how it informed your research?

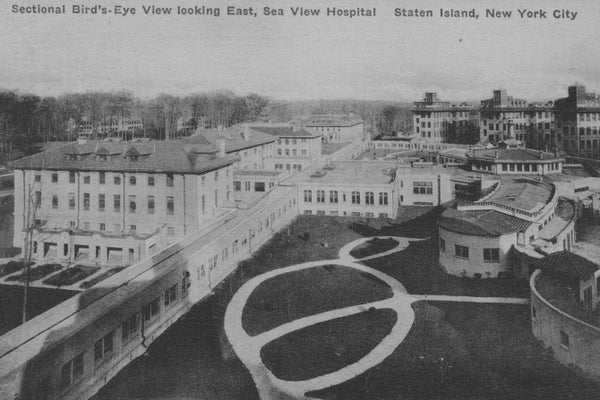

When I was a science editor for Springer Nature, I was reading a book on orphan [rare] lung diseases. It was this book of maybe 10 case studies. One of them mentioned this very rare lung disease, and the doctor who was writing it made a sort of cursory comment, like, “Well, I hope this medication becomes like the cure for tuberculosis at Sea View Hospital.” I was thinking, “What is he talking about?”I’m a New Yorker; I’m kind of a history buff for abandoned hospitals and anything that has to do with disease, so I started Googling it. And then up came the article about Sea View and the cure. Then next to it was this article about Virginia Allen. I found her through the Staten Island Museum, where she was speaking that weekend. So I went and I met her, and then for about six weeks, we met at a little cafe near Harlem Hospital Center [in New York City]. After that, she invited me to her home, which was in the restored nurses’ residence on the grounds of Sea View. We walked and talked, and she pointed at the buildings, and then she said to me, “Would you want to tell the story?” And I asked her, “Are there any archives?” She said, “No, there’s oral history, and I can tell you it.”

What were the nurses’ political lives like during this time period? Their work life and home life were very closely intertwined when they were living in the hospital that they were also working in and testing positive for TB themselves while treating ill patients.

So I can’t speak to exactly what political affiliation they belonged to, but they were very political in the sense that they were activists. They all were part of the NAACP [National Association for the Advancement of Colored People] and the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses. Missouria would often take in the sick; if a nurse didn’t have a family, she took them in. When I researched this book, one of the things that I came to realize was that Black nurses were activists from the outset. They were barred from the American Nurses Association [at the time], so they had to make their own way. They were very, very, very smart. Edna was, Virginia told me, a more quiet activist. She used her home in the later years to hold meetings, and she would raise money—she had a scholarship for young Black women to go to college.

Author Maria Smilios. Credit: Parker J Pfister

Your book puts readers on the front line of the tuberculosis epidemic and showcases the graphic nature of TB—it is a violent disease. There are explicit descriptions of some difficult medical procedures or experimental surgeries that were used at the time. How did you approach this part of the research, and why did you want readers to understand, and even experience, the graphic nature of the disease?

I wanted to banish the myth that tuberculosis is just a disease of the lungs and that all you do is cough. As you said, it is a violent disease; it ruins the body in unthinkable and fantastic ways. The microbe, as I say, is beautifully rendered to torture and to kill at a very slow rate. People don’t even know that they’re sick for weeks or months. I needed readers to know that it affected the tongue, brain and kidneys—it shrinks the kidneys until they’re just these two little useless nodules inside your body. I struggled with not wanting to gross people out, but I thought it was really important to describe the symptoms and procedures. This was a heavy mental toll on these women. Virginia said that Edna never talked about it, but Edna was a surgical nurse when ribs were taken out in bushels of six to 10 at a time. I also wanted it to go up against the pseudoscience because tuberculosis [had a lot of pseudoscience surrounding it at the time]. It would loom so large in people’s mind. They were so afraid of it, and it was also stigmatizing.

This book showed some eerie similarities between our experience in the initial height of the COVID pandemic and that of the average citizen during a tuberculosis epidemic. Could you tell me how your research and the writing of this book affected your perspective on COVID?

One of the things writers hope for is to be able to experience as much of our book as possible. So I went to Savannah, Ga., and to Clinton, S.C., and I also walked around Sea View. I never wanted to experience what it was like to live through a time when we had an airborne virus that had no cure. But I found myself in that position on March 13, 2020, with the rest of the world. Virginia called me early on, and she said to me, “Always have your windows open, and have fans and air moving because that’s what we did for tuberculosis.” In terms of the book, I had to rewrite it when COVID happened. I want people to be able to read this book and know that we really need to look at history because we’re in the midst of another COVID outbreak. And I thought it was really important for people to see how ridiculous it is that we’re in the same position now. It was terrifying to me because I knew it took almost nine more years for researchers to really tweak the drug for it to begin to work for tuberculosis. And I was like, “Oh, my God, do we have to go through this for nine more years?”

Can you tell me how you think the history of TB will help us in our fight against COVID?

Unfortunately, last week I read that there are about 500 active cases of TB in New York City, which is a rise of about 20 percent, compared with last year. These numbers make it the worst year for TB infection in more than a decade.

I think one thing we can take away here is that fighting tuberculosis was a global, democratic, long-sustained effort. There was no overnight fix. But most importantly, when an effective treatment became available, it was disseminated worldwide, and part of that happened because isoniazid was unpatentable, so costs for producing it and treating people with it remained low. And lastly, while there was still pseudoscience, the majority of people didn’t mount a collective effort to say it was “a fake disease.” They wanted it gone. When we reach that point, if we do, then I think we can really begin to end COVID.