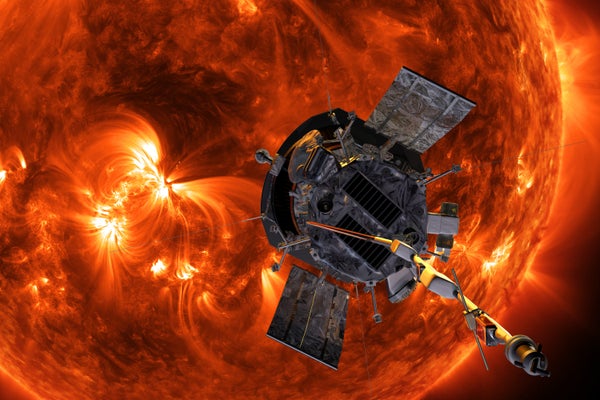

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe was built to withstand the ravages of the environment near our sun—and with good reason.

The car-size spacecraft has now flown through a giant solar outburst of charged particles called a coronal mass ejection (CME). If that CME had it hit Earth instead, it may have caused vast, continent-wide blackouts, scientists say. Some of those searing particles whipped through space at about three million miles per hour.

The encounter occurred on the far side of the sun, relative to Earth. It began on September 5, 2022, and lasted nearly two full days, scientists detail in a new paper published in the Astrophysical Journal. At the time, the Parker Solar Probe was a mere 5.7 million miles from the sun’s surface. Researchers typically have to study the sun’s outbursts from our planet, which treks an average of 93 million miles away.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The CME in question was the sort of event that scientists would prefer not to be able to study from Earth; they want such large outbursts to stay far from our planet. That’s because CMEs, which send bubbles of charged particles shooting out through the solar system, can cause geomagnetic storms near Earth that interfere with key aspects of our lives—such as the GPS satellites we use to navigate or the power grids that run our homes and offices.

The most powerful geomagnetic storm on record, called the Carrington Event, occurred in 1859, when humans had far less infrastructure that was vulnerable to such storms. Still, the Carrington Event had impressive impacts on the telegraph network and even lit some equipment on fire.

Had the September 2022 CME headed toward Earth, it could have caused a geomagnetic storm of about the same magnitude as the Carrington Event, said a Parker Solar Probe scientist in a recent Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory press release. Today if such a storm were to hit with no warning, it could cause blackouts spanning entire continents, physicists have said.

Fear of such a large, Earth-directed event was part of the inspiration for the Parker Solar Probe mission. NASA hoped the mission would shed light on enduring mysteries of the sun’s activity, such as how charged particles in the solar wind that constantly flows off the sun reach such high speeds and why the sun’s atmosphere—the corona—is so incredibly hot, much hotter than the star’s surface. By better understanding how the sun works, the theory goes, scientists should be better able to predict massive outbursts, giving Earthlings time to prepare for the storms.

The Parker Solar Probe launched in August 2018. The spacecraft was designed to sneak ever closer to the sun over the course of its seven-year mission. All along, scientists were excited by how the mission’s timing aligned with the sun’s 11-year activity cycle: the craft launched while the sun was relatively quiet, and activity was expected to peak in 2025, just as the mission would reach its climax.

Still, scientists have gotten more than they might have hoped for. Solar cycle 25, as the current period is dubbed, has been more active than researchers forecasted, with a host of outbursts such as CMEs and solar flares, which are made up of radiation.

Parker Solar Probe personnel hope the spacecraft will be able to catch more such events during the eight remaining close approaches to the sun planned for the rest of its mission. The spacecraft’s next solar flyby—its 17th—will occur on September 27.