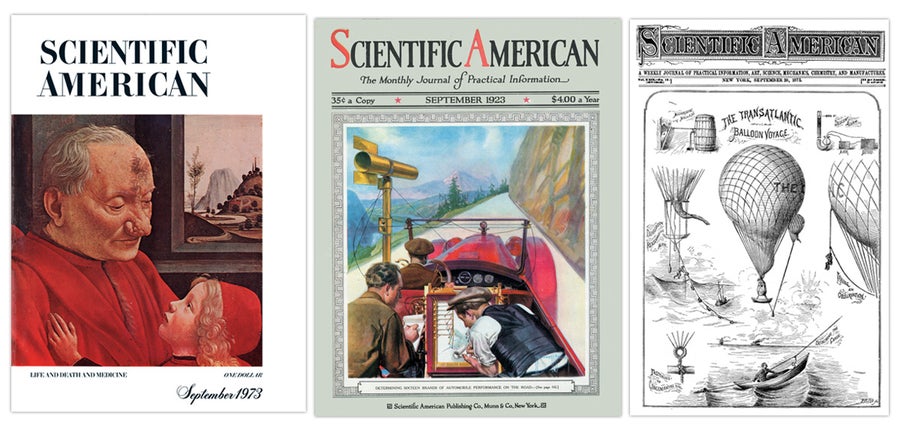

1973

Polywater's Final Exit

“The long-standing controversy over the existence of a superdense, polymeric form of water is apparently over. The argument began when Boris V. Derjaguin and colleagues at the Soviet Academy of Sciences observed that certain samples condensed in fine capillary tubes represented a new, stable form of water with a density almost one and a half times that of ordinary water and a molecular structure that could only be described as polymeric. Subsequent investigations in the U.S.S.R., Britain, Germany and the U.S. argued that the anomalous properties could be explained by impurities. Derjaguin has now reported that recent measurements by his group have revealed that their samples invariably contain trace impurities.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Drunk Intestines

“Alcohol is manufactured in the human intestine by microorganisms. The amount of pure ethyl alcohol (the potable kind) produced daily is about one ounce. Ethyl alcohol ingested by a human, or produced in the intestine, is carried to the liver. In the liver 80 percent is broken down by alcohol dehydrogenase; the remaining 20 percent is possibly metabolized by another enzyme, catalase. It is the efficiency of the process that so long masked the production of alcohol in the intestine. The microorganisms that produce it remain unknown.”

People with auto-brewery syndrome produce much more alcohol daily and may seem intoxicated even though they haven't been drinking.

The Jesus Lizard

“The basilisk lizard of Mexico and Central America has a unique ability: it can walk on water. In some areas this ability has earned it the name lagarto Jesus Cristo—the Jesus Christ lizard. Joshua Laerm of the University of Illinois photographed the animals with a high-speed camera. As the basilisk picks up speed, it twists the lower half of its body from one side to the other and thrusts each leg backward and to the side. The result is a rapid waddle, necessary to push itself ahead with maximum force and retract each leg from the water with a minimum of resistance.”

1923

Sixteen Ohms of Malaria

“‘You have sixteen ohms of malaria,’ exclaimed the man at the rheostat, to a member of the Scientific American staff who has been investigating the much-disputed Electronic Reactions of Abrams, a method of diagnosis and treatment developed by Dr. Albert Abrams of San Francisco. There are ERA practitioners throughout the country. Remarkable cures are said to be effected, including cases of cancer. But there are many doubters in and out of medical circles. The public, looking on, remains in a quandary.”

ERA was a huge medical hoax. It held that diseases have a unique vibration rate that could be sensed from a drop of blood, or a handwriting sample, and treated, all with Abrams's sealed electronic boxes.

1873

Superhuman Insects

“M. l'Abbe Plessis, in an article in Les Mondes, says that he placed a large horned beetle, weighing some fifty grains, on a smooth plank, then added weights up to 2.2 pounds. In spite of this being 315 times the beetle's weight, the beetle managed to lift it and move it along. A human is fully a hundred times feebler in proportion. Similarly, the flea, scarcely 0.03 of an inch in height, manages to leap over a barrier 500 times its own altitude. Imagine a human jumping 3,000 feet in the air!”

Speedy Pigeons

“Carrier pigeons are being thoroughly tested, and some have shown a wonderful speed. The Ariel, a pigeon that won the $2,000 prize in the international contest in Belgium in 1871, accomplished the distance between New York and Stratford, Conn., sixty-four miles, in thirty minutes. Another bird, known as No. 6, made the journey in almost as quick a time. The carrier pigeon seems to possess a memory for places, coupled with a very strong attachment for its abode.”