Summer is the season for stone fruit, pool parties, cookouts and, increasingly for Americans, ticks.

Ecologist Felicia Keesing had an uncanny sense for ticks for as long as she could remember. If one bit her, she could feel it and would quickly pluck it off with tweezers. But last year this superpower failed her when she didn’t feel a tick latch on. Keesing tested positive for Lyme disease, a tick-borne illness caused primarily by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, after finding the telltale bull’s-eye rash on the back of her knee. She started an antibiotic regimen right away and had no further symptoms, but the experience troubled her.

“It felt like I was being hypervigilant when I was doing checks [for bites] and things,” says Keesing, who studies the parasitic arachnids at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y., where ticks are thriving. “So I’m a little warier this year.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Keesing’s wariness is justified. Tick-borne diseases have been booming in the U.S., and tick abundance could spike this summer. Populations of rodents, a key host for ticks, are predicted to increase this year thanks to a large acorn crop in 2021.

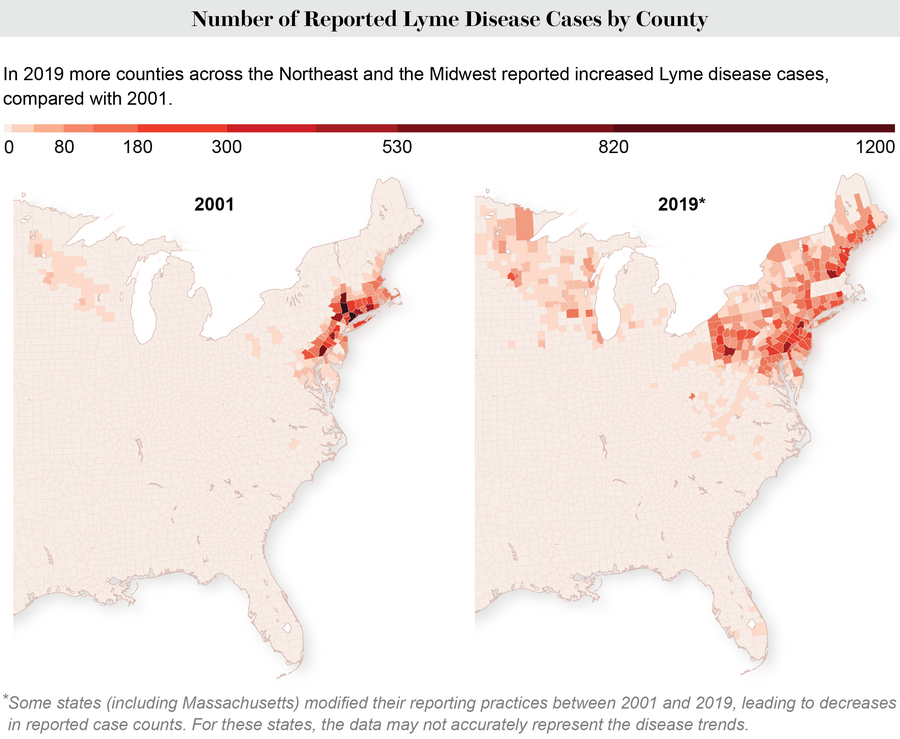

Roughly the size of a sesame seed, these semimobile sacks of blood trail closely behind mosquitoes for the top transmitters of disease. Ticks are responsible for about 75 percent of the 650,000 vector-borne disease cases that occur annually in the U.S. New England and the Upper Midwest have seen the lion’s share of increase in tick-borne illnesses, such as Lyme disease, anaplasmosis and babesiosis. Last month Maine recorded its first-ever death from the rare, tick-associated Powassan virus. But over the past few decades, various species of ticks have been migrating to new regions, leading to an increase in Rocky Mountain spotted fever cases throughout the South and mid-Atlantic.

“No matter where you are in the contiguous U.S., you can run into a different tick,” says Rebecca Eisen, a research biologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Credit: June Kim; Source: Lyme Disease Map, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (data)

The CDC does not actively track tick populations, so researchers typically rely on disease rates to study the parasite’s spread. The geographical spread of ticks has put more people at risk, but Keesing says it’s unclear whether risk has increased for communities with already high tick counts. While it’s tricky to predict the areas that will have more dangerous tick conditions, one thing is true: “If you live in an area with tick-borne diseases, and most people in the United States do, you should educate yourself about the times of year and the kinds of habitats that put you at risk,” Keesing says.

How Do Ticks Transmit Disease?

Ticks have four life stages: egg, larva, nymph and adult. At each stage after they hatch, they need to feed on the blood of hosts to molt and enter the next phase. Different tick species feed on certain animal species to survive. When a tick feeds, it may also pick up pathogens residing in the host’s blood—pathogens that may have been left behind from other ticks.

“If you’re a pathogen, being in the blood is not only a good way to get around someone’s body; it’s a good way to get picked up by [any] blood-feeding arthropod and get transported to a new host,” Keesing says.

Pathogens don’t automatically transfer once a tick latches on. Many ticks lack disease-causing viruses and bacteria in the first place, and even if they are present, different pathogens transmit at different rates. Some pathogens, such as the Powassan virus, can transmit in just 15 minutes. Borrelia burgdorferi, the pathogen that causes most Lyme disease cases, takes at least 36 hours to travel from a tick’s gut into a host’s bloodstream. Diagnosing Lyme disease is tricky because B. burgdorferi stays in the skin initially after being transmitted, leaving comparatively low levels of antibodies in the blood for a few weeks that make the disease difficult to detect.

Eisen says bites shouldn’t be taken lightly. Tick-borne diseases can cause severe symptoms, such as joint pain, nausea, facial paralysis—and even an allergy to red meat. Fatal cases are very rare, but it’s important to be aware of ticks and the dangerous pathogens they carry.

There are 30,000 cases of Lyme disease reported to the CDC every year, but most experts agree that figure is a substantial undercount. One study suggests that there are potentially half a million annual Lyme disease cases in the U.S. Lyme disease receives the most attention and has the highest case count among tick-borne diseases, but there are 17 other known pathogens that cause human illnesses, and six newillnesses have been discovered in the past 20 years. Scientists believe that a greater awareness of illnesses, rather than an expansion of the pathogens picked up by ticks, is responsible for the increase in illness types.

Why Are Ticks and the Diseases They Carry Spreading?

Ticks and tick-borne illnesses are on the uptick because of three factors: climate change, an increase in tick habitats and a growing awareness among health professionals.

Warmer temperatures and increased humidity caused by climate change are likely making it easier for ticks to survive in northern climates and thus increasing the potential for disease transmission, though somestudies suggest that a dry summer could kill and regulate the spread of the parasites. Many of these studies were conducted in a controlled laboratory setting, however. A recent study tracking ticks’ survival rates outdoors showed a surprising resilience to extreme hot and cold temperatures.

“Ticks are little tanks,” says Keesing. “We look at them as being fragile, but they move up and down in the forest soil to [regulate] their temperature.”

While scientists are unsure how weather patterns affect or predict summer tick activity, they do know that as ticks’ geographical range increases, tick-borne illness also increases. Tick populations are typically lower on the West Coast than in the eastern U.S., but Lyme disease rates have been rising in California as well.

Tick-borne diseases spread through the migration and behavior of animal hosts. For example, deer and rodent habitats are increasingly overlapping with human communities—and all three species are hosts for the blacklegged tick, also aptly named the deer tick. As humans have built more homes on the edge of forests, deer and rodents have brought this tick species into homes, yards and other infrastructure.

Without a host, ticks don’t move great distances—barely three feet in 30 minutes, according to one study. “They’re not going to chase you when you’re out running, they’re not going to fall from the trees, and they don’t fly,” Eisen says. “But it’s good to be aware that there is a risk and take precautions” if you go outdoors.

People should stay vigilant, especially because many tick-borne diseases lack the bull’s-eye rash at the bite site, says Bobbi Pritt, who studies these diseases at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “Just like you should be putting on sunscreen,” Pritt says, “you should also be wearing a tick repellent and checking yourself for ticks when you come [home]. Just make it part of your routine.”

How Can You Avoid Getting Bit?

In order to avoid tick bites, wear long clothing, stuff your pant legs into your socks and consider treating your clothes with permethrin insecticide to avoid unwanted passengers. Environmental Protection Agency–registered tick repellents, especially those containing DEET, are also effective at keeping the parasites and other bugs away. Avoid obvious tick habitats such as shady brush, even if it’s in your own yard. When you return home, throw your clothes in the dryer and do a thorough check for ticks on your body. Ticks love nooks and crannies, so pay extra attention to damp spots such as your armpits or the backs of your knees. Also check your dogs because dog ticks can carry Rocky Mountain spotted fever, which can also infect humans.

Even with these preventive measures, if you see a tick lodged on you, skip the matches or nail polish and resist the urge to pick it off with your fingers—you’ll only leave the tick’s mouth lodged into the skin. Instead use tweezers and pluck at the site of the bite as close to the skin as possible. If you’re planning to go camping in areas with known high tick counts, carry fine-tip tweezers—they could save your life. The CDC advises to consult your health care provider after noticing a tick bite if you start to experience flulike symptoms such as headache, chills or fever. It’s always best to catch tick-borne illnesses early.

Tick-borne diseases are scary, and the geographical spread of ticks into new communities is concerning, but don’t let the fear of a tick bite keep you from enjoying a beautiful summer day outdoors. Just keep a careful eye out for those pesky parasites, Keesing says.

“None of [these preventative measures] makes being outside feel all that glamorous,” she says. “It takes away some of that sense of freedom that we feel, but I’ve been living in this area for decades now, and it just becomes part of your practice. It’s just what you do.”