A team of US-based researchers has created an innovative technique that uses diamond microparticles to enable simultaneous optical and MR imaging – a major breakthrough that could pave the way for faster and deeper medical imaging. So, how does the new technique work in practice? What are its advantages over existing imaging approaches? And what are the key research and clinical applications?

Deeper high-resolution images

When researchers or clinicians want to look closely at living tissue, they face a trade-off between the depth and clarity of the images that they can capture. This is because light-based, or optical, microscopes provide detailed, high-resolution images – but only up to depths of around a millimetre. Conversely, MRI uses radio frequencies capable of reaching all parts of the body, but can only capture low-resolution images.

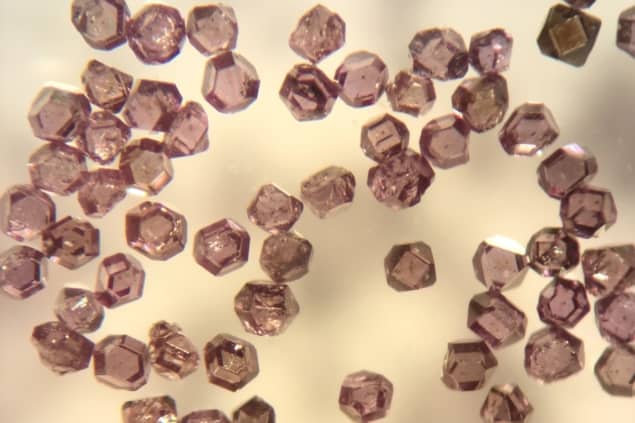

In an effort to overcome these limitations, a research team headed up at the University of California, Berkeley, has demonstrated how microscopic diamond particles can be used to capture information from MRI and optical fluorescence imaging at the same time, potentially enabling observers to obtain high-resolution images up to a centimetre beneath the surface of tissue – 10 times deeper than existing approaches using just light. The researchers describe their new technique in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

As author Ashok Ajoy explains, the new method makes use of both optical imaging and hyperpolarized MRI – the first ever implementation of such a combination. The technique uses diamond microparticles with nitrogen vacancy defects that optically fluoresce and allow the nuclei in carbon-13 (13C) atoms in the surrounding lattice to be spin hyperpolarized, which allows the diamond particles to light up in MRI.

“In combination, these two imaging modes have a lot of complementary features that make them attractive. Especially powerful is the fact that the imaging in the two modes occurs in Fourier reciprocal spaces,” says Ajoy.

Key applications

The research team envision using the technique primarily for cellular studies and examining tissue samples outside the body. Other likely applications range from helping with the identification of chemical markers of disease in blood to physiological studies in animals.

“While there is wide literature showing that diamond is non-toxic, we don’t envision using these particles inside the body natively,” Ajoy says.

That said, methods by which the diamonds are used to spin hyperpolarize other analytes – for example, water – which can then be injected into the body, might open exciting new background-free avenues of MRI imaging in angiography, he adds.

According to Ajoy, a key advantage of the combined approach is that, by using two modes of observation, it could allow faster imaging. Diamond tracers are also low cost and comparatively simple to work with in research and clinical settings – potentially broadening access to inexpensive nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques in the future. Other advantages of the new method stem from the fact it provides better imaging in scattering or optically dense media.

Spin-enhanced nanodiamonds could improve disease diagnosis

“Moreover, these two modes – optics and MRI – sample the image in two Fourier reciprocal spaces, known as x- and k- space. It’s like seeing the same object simultaneously in two conjugate modes; this can yield interesting new ways to significantly speed up image acquisition,” Ajoy says.

Moving forward, Ajoy confirms that the research team has already embarked on the next phase of research, which will focus on enhancing the functionality of the diamond particles. “We are attempting to endow the particles with chemical sensing capabilities so that they can provide information on their local chemical environment via their optical or MRI signatures,” he adds.