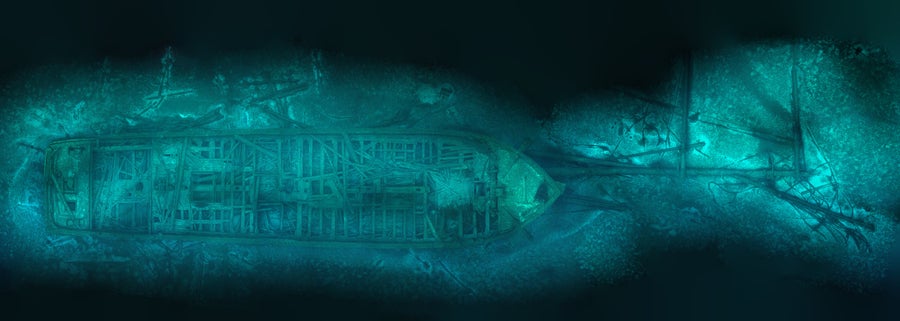

Gray blotches poke up from the murky depths of Lake Michigan in an image on maritime archaeologist Tamara Thomsen’s computer screen. These are the remains of the SS Wisconsin, an steel-hulled steamer that sank in 1929 off Kenosha, Wis., after a storm engulfed the vessel during a routine passage between Chicago and Milwaukee.

The shipwreck of the SS Wisconsin is one of hundreds believed to be lurking in Lake Michigan’s depths (which reach a maximum of 923 feet), says Thomsen, who works with the Wisconsin Historical Society’s Maritime Preservation and Archaeology Program. Little is known about most of these sunken craft, and diving to study them can be dangerous and expensive. But in June the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration designated a 962-square-mile section of the lake north of where the SS Wisconsin rests as the Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Marine Sanctuary. The move could take Thomsen and others a giant step closer to exploring the region’s underwater artifacts in unprecedented detail—and to bringing its unique and often overlooked maritime history into much sharper focus.

Thomsen has made 300 dives at more than 250 sites in Wisconsin waters, where her explorations and documentation have led to 41 shipwrecks being nominated to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. She says the new sanctuary’s protections will enable her and other maritime archeologists to study shipwrecks remotely without having to visit the sites in person. The key tool is a type of digital three-dimensional modeling known as photogrammetry, which will allow researchers to examine the SS Wisconsin and other Lake Michigan shipwrecks at a level of detail not seen since the vessels made their final voyages many years ago.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Before the new designation, funding was severely limited, hindering Thomsen’s ability to research the lake bed. Along with giving researchers access to federal funding, the new designation will provide additional photogrammetry resources, stricter diving regulations to protect the shipwrecks and added expertise from partnerships that could enable deeper insights into the region’s history—including the Great Lakes’ role as a major shipping passage beginning in the mid-19th century.

Thomsen and Caitlin Zant, a maritime archeologist at the Wisconsin Historical Society’s Historic Preservation division, typically had relied on a database of historical newspaper clippings and insurance documents to search for possible shipwreck sites on the lake bed. “It was like looking for a needle in a haystack,” Thomsen says. “Right now we’re contending with a backlog of shipwrecks to explore, so having more expertise [and therefore more eyes on the shipwrecks], is certainly advantageous for us since there’s always something new to learn and discover.”

The designation marks a first for Lake Michigan and is only the second of its kind in the Great Lakes. Since the protections took effect this summer, the Wisconsin Historical Society has partnered with Marine Imaging Technologies, an underwater-optical-imaging-system provider based in Massachusetts. Using specialized cameras that the tech company developed in an earlier collaboration with the National Park Service, Thomsen and her team have gone on limited dives to some of the three dozen known shipwrecks resting at the bottom of the sanctuary. The divers steer a frame mounted with three of the cameras to capture clouds of data points, which software later transforms into photogrammetric 3-D imagery. In the future, Thomsen plans to use this technique to find unknown shipwrecks by getting a closer look at potential sites using digital technology rather than relying on a diver’s naked eye alone.

The Rouse Simmons schooner sank in 1912 in Lake Michigan while hauling a load of Christmas trees. Credit: Courtesy of Tamara Thomsen, Maritime Archaeologist, State Historic Preservation Office, Wisconsin Historical Society

The mounted Nikon mirrorless cameras can capture more than 10,000 45-megapixel images per hour underwater, according to Marine Imaging Technologies. Specialized software then pieces the images together to create a 360-degree view of a wreck. This lets researchers virtually tour and interact with a site from their computers whenever and wherever they choose rather than having to repeatedly travel to a site and strap on scuba gear.

So far, Marine Imaging Technologies has created 3-D models of two wreck locations: those of the SS Wisconsin and the SS Milwaukee. Both are particularly vulnerable to degradation, not only from being submerged in water for close to a century (coincidentally, the SS Milwaukee, a train-car ferry, sank in a storm seven days before the SS Wisconsin met its demise). Looters also have damaged both wrecks, which are popular exploration sites among scuba divers.

“We were hearing from divers who were noticing changes to the SS Milwaukee,” a wreck that recreational divers first started to explore in the 1970s, Thomsen says. “They said it was breaking down and degrading faster, but of course, this is all anecdotal. [With a model of a] site, it’s easier for us to understand where those changes are happening.”

A possible culprit in the degradation of the SS Wisconsin and SS Milwaukee that Thomsen and her co-author had cited in a preliminary report on the former is “the introduction of invasive species,” specifically zebra and quagga mussels. These two mollusk species often latch onto iron, steel and other hard materials that are commonly used in ship making. This encrustation can speed up corrosion and obscure a ship’s appearance over time, making it harder to analyze the degradation of the shipwreck.

In the face of these various threats, the 3-D models serve as baselines that researchers can use over time to monitor any changes to the shipwrecks. This could prove crucial for protecting these sites, Thomsen says, because it shows instances of degradation in the form of “before” and “after” images. “Basically, we’re taking different point clouds and looking for differences there, and then you can do a subtraction model of [each shipwreck site],” she says.

Having 3-D models of a wreckage site lets researchers remotely establish how it is changing over time, she says. “You can go back in a year or five years or 10 years and look at degradation, predict where changes might occur and then create management tools or plans of action based on that,” she adds.

The new protected status and subsequent research it allows will likely further the field of underwater archeology as a whole, says Carrie Sowden, archeological director of the National Museum of the Great Lakes in Toledo, Ohio, and an underwater archeologist studying wrecks in Lake Erie. The designation also puts a national spotlight on the cultural heritage of the Great Lakes, she notes.

“People often forget that the lakes were an important transportation pathway and a major driver of development and immigration in the 19th and early 20th centuries,” Sowden says. “This designation brings more awareness to the impact that the lakes have had at both a regional and national level.”

In the near future, Thomsen plans to apply what she is learning from the current 3-D models to the backlog of known and yet to be discovered shipwrecks within the sanctuary. The only data marine archeologists currently have at their disposal are written accounts of a ship’s disappearance and, in some cases, reports from archaeologists who have explored the sites. The 3-D models will help build a more definitive and reliable narrative of a ship’s whereabouts and state of degradation.

The new designation also prohibits grappling hooks and anchors to sites where a mooring buoy is present, and it enables the installation of specialized moorings that would allow vessels to anchor at wreck sites with minimal disturbance to wrecks or the lake bed. Such moorings should have a negligible effect on aquatic life and habitats, according to a 200-plus-page environmental impact study conducted by NOAA.

“The sanctuary designation is meant to protect, promote and allow research on these cultural resources,” Thomsen says. “I’m hoping that people will recognize the value of these resources and, more than anything, understand that it’s not just the hard facts that we’re discovering but a feeling of appreciation of, culturally, what it is we have.”