by Grace Lee Kang

While out in the waters of the Stillaguamish Estuary, the marsh where the Stillaguamish River meets Port Susan Bay, Nature Conservancy Aquatic Ecologist Dr. Emily Howe and Skagit River System Cooperative (SRSC) Lead Field Biologist Brian Henrichs witnessed something they had never seen before. And one urgent question was running through their minds—where have all the Chinook gone?

Illustration by Erica Simek Sloniker / The Nature Conservancy.

In conducting fish sampling across the estuary for a collaborative research and monitoring effort in the spring of 2022, it became clear there was a precipitous drop off in the number of juvenile Chinook salmon compared to previous years. “We go out twice a month to monitor a suite of 25 sites across the estuary and Port Susan Bay. We set and pull up the net from the same set of sites, week after week from February through August. But this year, the Chinook weren't showing up. In fact, hardly anything was showing up,” Howe recalled.

In Puget Sound, April is typically a time of peak outmigration from the rivers into the estuary for juvenile Chinook. Last year’s numbers were staggering. The research team was only able to catch a fraction of their allotted research quota, a planned total of 80 fish to be collected from April through June. With such drastically reduced catches, Dr. Howe and her research partners first wondered, “Is there something about the way we're setting the nets? Are we just not successful at catching them this year?” Eventually, they began to ask a different question: “Is there a much larger story here?”

360 Video [Click and drag to move around]: Take a ride through the Stillaguamish estuary as researchers travel between fish monitoring sites.

Piecing together the larger story with local partners

Searching for answers, Dr. Howe and her collaborators at the Skagit River System Cooperative, which provides natural resource management support for the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe and the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, reached out to tribal, state and county managers on the Stillaguamish and other rivers to confirm if they were seeing similar numbers.

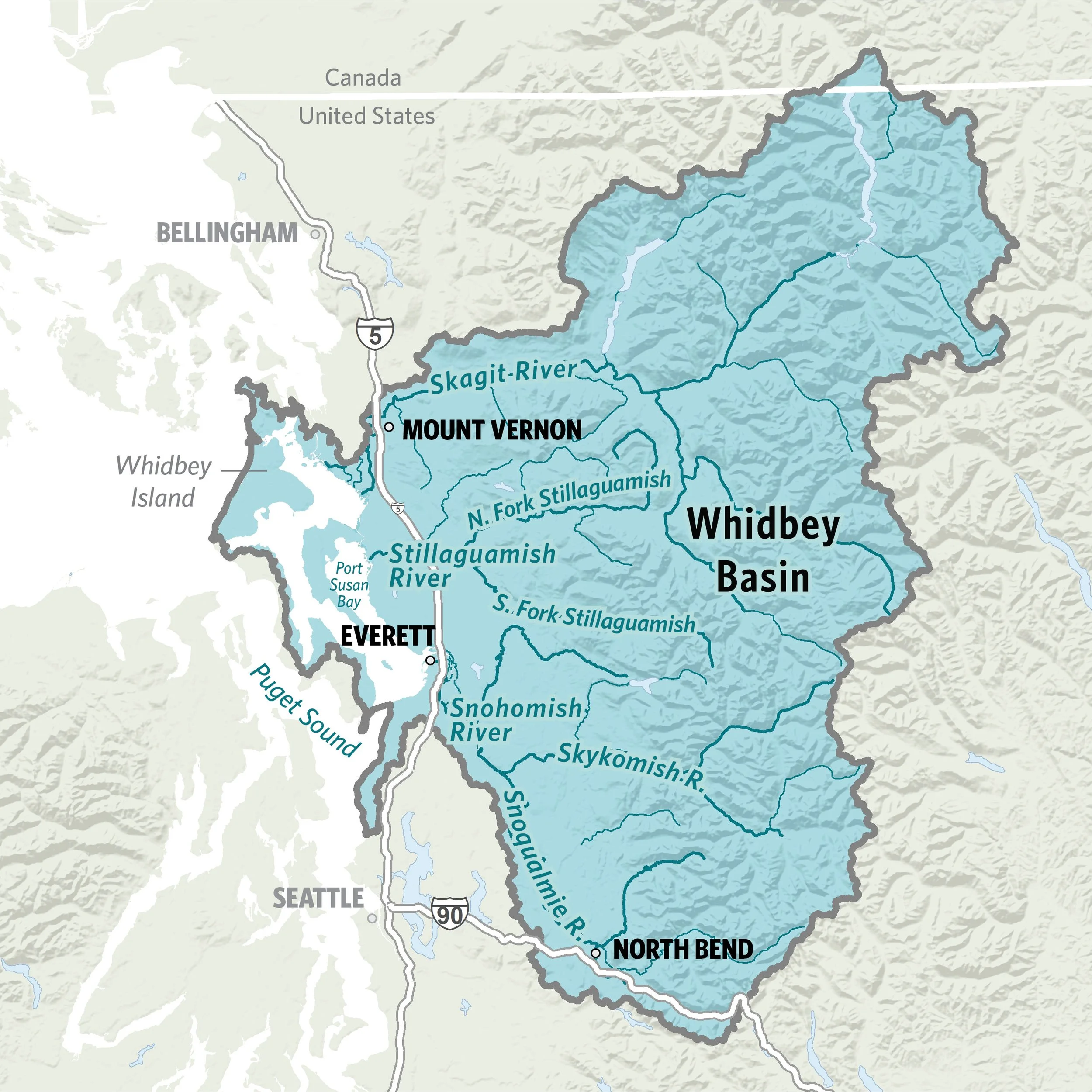

Whidbey Basin. Map: Erica Sloniker\TNC.

The story was the same across the Whidbey Basin, which includes the Skagit, Stillaguamish, and Snohomish Rivers: the juvenile Chinook numbers were much lower, and later to arrive. On the Stillaguamish River, outmigration—when salmon leave their home stream to mature in the ocean—was less than 5% of normal April numbers. The numbers picked up in May (a delayed peak is normal for cold, rainy springs), but were still low. On a given day during peak outmigration, there should be hundreds of fish going through upriver smolt traps, the tools used to count fish moving downstream on their way to the estuary. But there were only a few dozen moving through the traps each day this past spring. Final outmigration estimates are still forthcoming for the Whidbey Basin rivers, but seem to be hovering around 30% of normal.

360 Video [Click and drag to move around]: Join the Stillaguamish research team as they set the beach seine, then identify and measure the catch.

There wasn’t anything wrong with the way Howe and Henrichs were setting the nets, after all. The fish just weren’t there this year. “No matter where we were in the estuary, the channels were quite empty of Chinook,” said Howe. “It was a moment where you feel what you know, you feel it in your gut. And it's a really different way of knowing a system and a problem.”

While we don’t have a definitive answer as to why there were so few Chinook outmigrating this past season, signs point to last winter’s unprecedented flooding and a warming climate that increasingly supports large storm events. In November 2021, a series of back to back atmospheric rivers slammed into the region with record rainfall, inundating floodplain communities and catastrophically crumbling infrastructure. The flood events were also hard on this generation of salmon; it’s likely most of the Chinook eggs incubating beneath streambed gravels were simply washed away.

Juvenile salmon collected in the estuary are generally smaller than your index finger, measuring just 40-60 mm long. Video: Emily Howe\TNC.

Salmon populations have been declining for decades from a multitude of factors including habitat loss, toxic stormwater runoff, dams, and warming waters. James Schroeder, Washington State Conservation Director for The Nature Conservancy, ties most of these threats to salmon back to one principal culprit: climate change. “Climate change encompasses many types of threats and affects salmon across their entire life cycle, even in remote areas,” Schroeder says. “Young fish need cold water—rivers are warmer, oceans are warmer, current patterns and upwelling are changing, more runoff causes more urban pollution.” And, Schroeder points out, because of salmon’s expansive migration and range, their recovery faces a more complex challenge than that of many species. “With other endangered species, you can circle a spot on the map to target for restoration,” he says. “But salmon are different. You can’t just fix one area.”

Tribes Leading the Way

Mike Cladoosby, a member of the Swinomish Tribal Community, smokes freshly caught salmon filets at his home near the Skagit River in Washington. Photo: Bridget Besaw

As co-managers and leaders in salmon recovery, Tribal Nations see and feel the impact of declining salmon throughout their communities. According to the 2020 State of Our Watersheds report, as the salmon disappear, tribal cultures, communities and economies are threatened like never seen before. Some tribes have even lost the most basic ceremonial and subsistence fisheries that are a foundation of tribal life and culture.

Yet, there is a sense of hope when looking through the lens of long-term progress. Tulalip Tribes Director of Natural Resources Jason Gobin notes, "There have been strides made [compared to 30-40 years ago], with the science to better understand these life cycles and processes for salmon and river habitats. This understanding will help guide us as we continue to make the march up the hill to carry these salmon forward for future generations.”

It will take an ongoing commitment to preserving a vital resource for everyone. "It's important work which is why we do it the right way with the right approach, for instance trying to deed restrict the properties we purchase to protect them. When they’re set aside for fish and wildlife, for treaty rights, that benefits all of us—even those who aren’t in Tribal Nations," says Jason Griffith, Environmental Manager for the Stillaguamish Tribe.