Images of the human body’s most complex and intriguing organ often never make it out of a laboratory. The Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience’s annual Art of Neuroscience competition began as a way to peer into this unseen world. Year after year, submissions have depicted the minutiae of the brain’s tangle of blood vessels and neurons, revealing the beauty at the intersection of the artistic and scientific realms. Now in its twelfth year, the competition has elicited a deeper response, with many artists challenging how we think about the brain.

Organizers this year asked for submissions simply related to the field of neuroscience in its broadest sense. The competition awarded one winner, four honorable mentions and two editor’s picks out of more than 150 submissions.

Some submissions remain thoroughly scientific, proving that the brain is a work of art in its own right. Whether they depict microscopic images of the thin strands of tangled neurons or diseased neurons in a state of disequilibrium, these entries offer a rare glimpse into the technical outputs of brain research. Other submissions invoke a less literal representation of the brain’s inner workings and seek to demonstrate the very real-world ramifications of a complex disorder or challenge long-held societal beliefs. Neuroscience may still take place in the lab, but visualizations of the human mind are as expansive as we are.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

WINNER

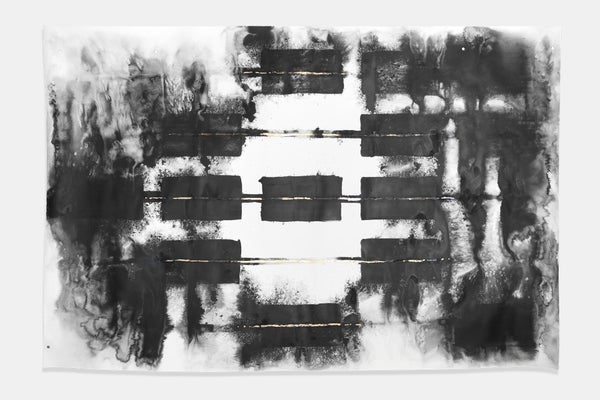

Various photographs of the artwork of the FND Stories art project. Credit: Andrew J. Brooks

FND Stories

by Andrew Brooks

People who live with functional neurological disorder, or FND, describe the experience of living with the condition as “frustrating, debilitating and misunderstood,” says Andrew Brooks, an independent artist and an architecture tutor at the University of Edinburgh. Using silent video, text-based AI analysis and combinations of ink and gold leaf on paper, Brooks, draws attention to the condition that, for centuries, doctors have struggled to describe.

According to one analogy, if your brain were a computer, functional neurological disorder wouldn’t be caused by damaged hardware but by malfunctioning software. With no specific test to identify the disorder, no tell-tale symptoms and no single treatment, FND has been misidentified throughout history as a nervous system disorder, conversion disorder and even “hysteria.” Some people might experience seizures, loss of limb function, tics, facial spasms, difficulties with speech, and loss of hearing and vision. Stress and trauma are part of the reason why a person might develop FND, but those experiences are not the main driver. Instead the debilitating condition stems from abnormalities in how the brain functions and processes information, and pathways in the brain do not function as they should.

Brooks has a personal connection to the disorder. In 2015 his wife was diagnosed with the condition following a bicycle crash. In the aftermath and treatment that followed, Brooks felt compelled to create something that showed the reality and emotional experiences of people living with the misunderstood condition.

In six face-to-face interviews with participants living with FND, Brooks read their favorite childhood stories out loud—Pride and Prejudice, a Dr. Seuss book or a book of poetry written by a family member, for example—and filmed their reactions. After reading the stories, he had a long conversation with each participant about life with the disorder. The resulting work is a video of the interaction with the sound removed. “You can just see them reacting or talking, with the intention being to connect with them on a body-language level,” Brooks says.

Brooks then ran the tape through data- and text-mining software and pulled out more than 3,000 words that the participants used when talking about their life with the disorder. He found that the words that had the most co-location—or were used alongside each other the most—pointed to the psychological toll of the illness: mental health, bad day and good day.

Brooks says that the participants felt it was reassuring to know others were going through the same emotions and feelings associated with the condition. Someone who had seen the exhibit wrote on X (formerly Twitter) that 15 years of grief and shame melted off his shoulders. “That really kind of floored me,” Brooks says. “The reaction has been stronger than I could have hoped for.”

HONORABLE MENTION

Martians Incubation Lab

by Hung Lu Chan

What does a Martian look like? All manner of green-skinned creatures with wide, buglike eyes and wiry limbs have dominated pop-culture interpretations of life on Mars for decades. Even before Hollywood imagined the first alien on screen, the myths of Mars have been tangled with religion, folklore and early scientific inquiry. But the mystique shrouding the Red Planet isn’t only borne out of curiosity; the human fascination with its mythical inhabitants reflects our inner fear of the “other,” says Hung Lu Chan, the artist behind Martians Incubation Lab.

With a blend of neuroscience and mental imagery, Chan’s work is a 20-minute meditation that guides participants to look for their “inner Mars.” The practice peers into the complex relationship between human and alien and reveals that the concept of an alien begins from the inside, Chan says.

The meditation asks participants to imagine placing themselves within the environment and atmosphere of Mars using descriptions of the planet’s carbon dioxide–filled air, freezing temperatures and dust storms. “If you become part of the dust, maybe you can respect this planet more,” Chan explains.

Throughout the experience, electroencephalogram (EEG) electrodes capture the neurofeedback of participants, who are then asked to interpret the sound and motion graphics created with the data.

Chan describes Mars as the most stigmatized planet—the place where the first evil aliens originated from human imagination. He says the idea of “evil and invasive” Martians still pervades modern science and media representations of the planet.

Reflecting on the Western colonial underpinnings and exploitative intentions of our future plans to inhabit Mars, Chan says these imagined “others” reflect our own biases and fears. “To reshape a more inclusive future, I think we really need to look into and analyze the creator of all these aliens, which is the human mind,” Chan says.

HONORABLE MENTION

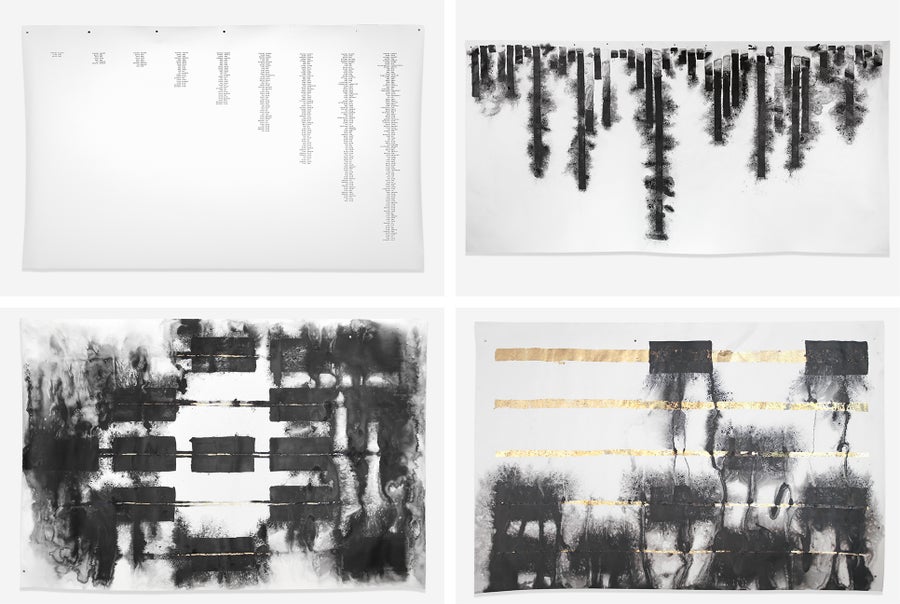

Credit: Bart Lutters

The Forgotten Giants of Neuroscience

by Bart Lutters

Whether hunched over a microscope or wielding a surgical knife, scientists of the past have conducted years and years of research and experimentation that add up to what we know about the brain.

But the people behind those experiments—whose cells were magnified under the lens and whose bodies went under the knife, willingly or not—are often left out of the collective memory of these great achievements.

In his research as a medical historian, Bart Lutters, the artist behind The Forgotten Giants of Neuroscience, says he encounters countless photographs of patients in the archives of scientific experiments. “All of a sudden you realize, wow, these were actual people,” Lutters says. “We experimented on actual lives and people who were often very sick, ill, suffering individuals.”

Lutters created a series of portraits based on real images of patients found in archives in the Netherlands but deliberately changed the features of the patients for anonymity.

Using mixed media, Lutters pieced together the features of the patients against a background of notes scribbled down by physicians and scientists. The notes are from real patient files, but they don’t correspond with the person depicted in the portrait. By making the portraits a collage, the works show that history-making is a subjective process. “Like a puzzle, we put [it] together from different angles, which allows us to reflect on the past but never to reconstruct it as it was,” Lutters says.

Lutters’s work intends to “restore the lost voices” of medical history by telling the stories of the people who were not deemed worthy of historical attention.

“We’re only celebrating the achievements, and we forget that it’s dependent on the cooperation of a lot of people,” Lutters says.

HONORABLE MENTION

Plassein, 2022

by Alexandra Davenport

Plassein, derived from the Ancient Greek word meaning “to mold or to shape,” underpins the choreographed interpretation of neuroplasticity by Alexandra Davenport, a dancer and artist based in Birmingham, England. Fascinated by reorganization, adaptation and growth in her work, Davenport was inspired by the malleability of the brain in developing the sequence.

The idea of the brain as a fixed entity has persisted throughout the history of science, Davenport says. “You get to a point in your life, and it’s like, okay, this is your brain, this is how it is forever,” she says. “But actually what neuroplasticity tells us is that it’s the exact opposite.”

The performers begin with interlocked arms, crouched low on the ground. With each turn of the camera, the dancers’ arms shift from one person to the next, with their bodies eventually standing together in a jumbled clump of limbs. Later in the performance, the dancers begin to mirror each other’s movements, standing face-to-face in the empty warehouse in which the performance was filmed.

The movements mimic the constant transformation of the brain. “It is formed through our experiences,” Davenport says. But it’s also formable, meaning that we can influence the way the brain develops, she explains.

The camera is an additional character in the work. Constantly in flux, it moves behind the pillars and remerges to a changed scene with the dancers repositioned on the ground. The style of filming leaves the viewers guessing the subsequent movements, Davenport says.

Merging art and science allows the latter to become more accessible, Davenport says. “Neuroplasticity is very, very complex,” she says. “But you can take the principles of these things and relate them to people’s everyday lives and help them think about things in a different way.”

HONORABLE MENTION

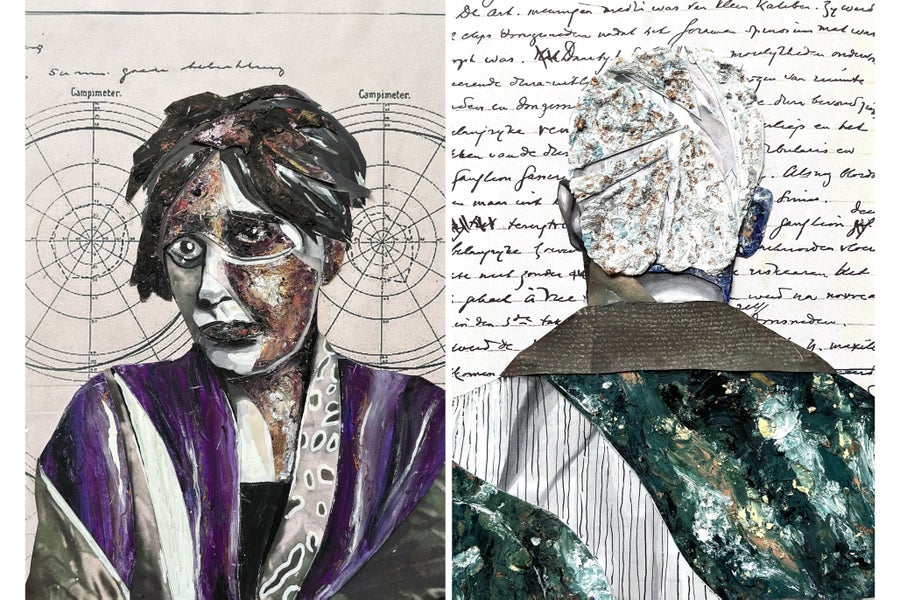

Credit: Lucia Rohfleish. Astrocyte endfoot, neurofibrillary tangles and beta-amyloid created with BioRender.

The Alzheimer’s Eye

byLucia Rohfleisch

Inspired by her research on the diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases, Lucia Rohfleisch, a master’s student and an independent artist based in the U.K., wanted to take a closer look at the eye as a window to the brain.

For Alzheimer’s disease, a correct diagnosis requires an investigation of specific diagnostic markers, Rohfleisch says. The three main focuses are on neurofibrillary tangles, amyloid-beta and cerebral atrophy. But there are other features that might be important as well, she says. One of those are changes to the retina. The intention behind the artwork is to “encourage a closer look at potential diagnostic markers that may not first come to mind when thinking of Alzheimer’s,” Rohfleisch wrote in an e-mail.

EDITOR'S PICK

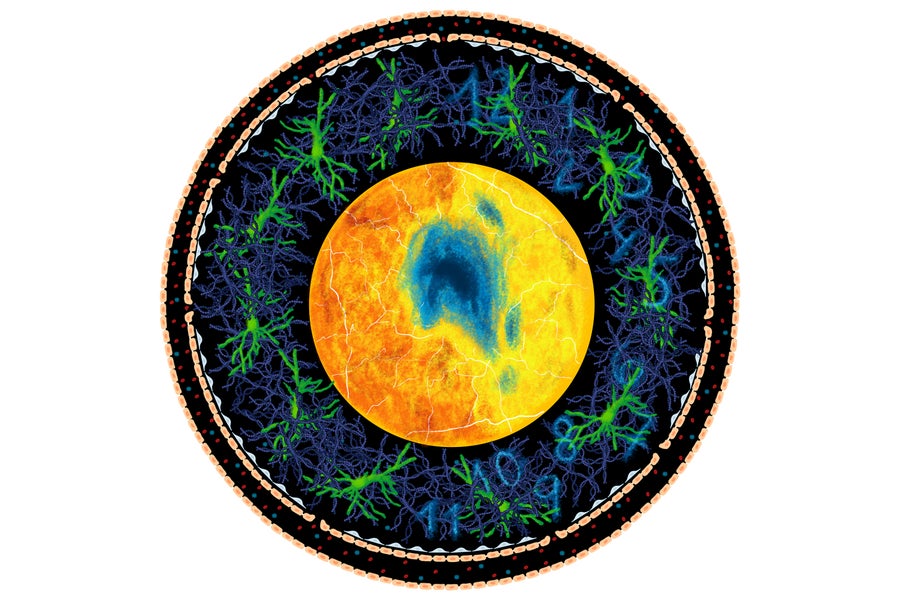

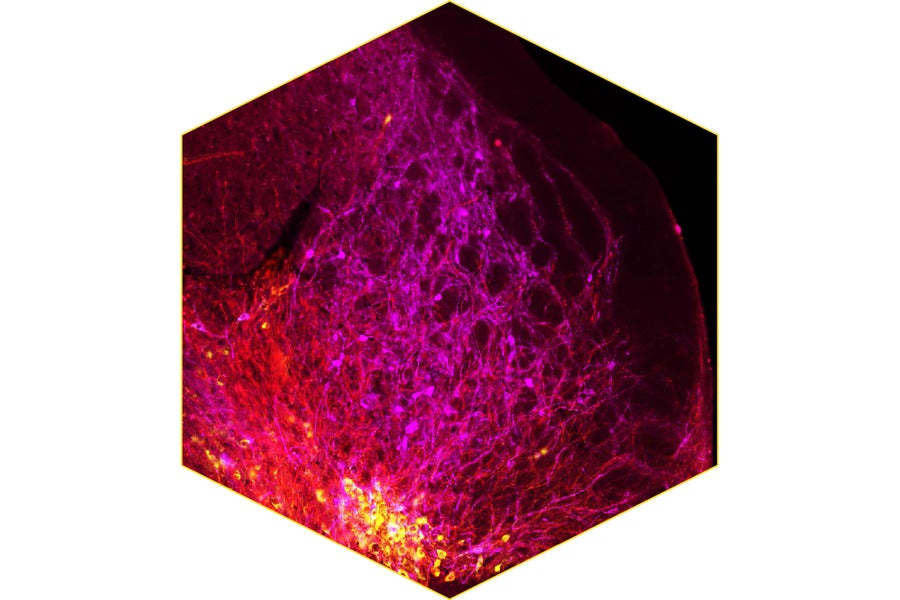

Credit: Lennard Klein (image/artwork processing); Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience (NIN)/Neuromodulation and behavior group/Lennard Klein, Anastasia Markidi, Rudolf Faust and Ingo Willuhn (data)

Fiery Webb

by Lennard Klein

Look closely at this image and you’ll notice where the tiny tendrils, brightly colored in red, magenta and yellow, connect. These are neurons from the brain of a rat that have been visualized under a microscope in a neuroanatomical study. The three distinct colors represent different subsets of neurons. For example, the magenta neurons come from the ventral part of the brain.

EDITOR'S PICK

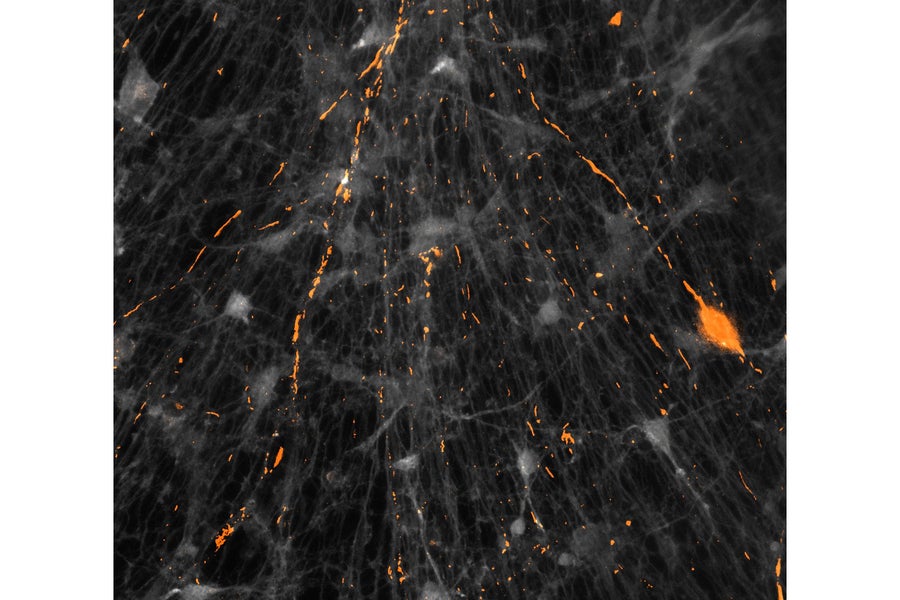

Credit: Ammar Natalwala (from research conducted at the University of Edinburgh and funded by the Wellcome Trust)

Erupting Neurons

by Ammar Natalwala

Ammar Natalwala, the scientist behind this submission, likens the thin, fiery orange lines punctuating a textured black surface in this image to an active volcano. But these striking strands of black, white and orange in fact represent Parkinson’s disease in a petri dish.

Natalwala transformed human stem cells into mature neurons and used Lewy bodies—the clumps of protein found in brain plaques typical of Parkinson’s disease—to push them into a diseased state. The imbalance triggered by the protein can be observed under a microscope, offering a closer look at how the proteins tear apart the brain’s ability to perform basic functions.