The prospect of learning a new language can be daunting, especially for an adult. Spending dozens of hours a year on lessons just to make slow progress on a new skill can seem like too much—particularly for someone who is juggling work and family responsibilities as well. That was certainly how one of us (Milkman) felt about her decades-long ambition to learn Spanish.

That all changed, however, when a popular language-learning app presented a more attractive approach: complete one lesson—just six or seven minutes long—each day to eventually become bilingual. This adds up to about 40 hours of study per year, the equivalent of a full work week, but it is presented as a bite-size daily commitment.

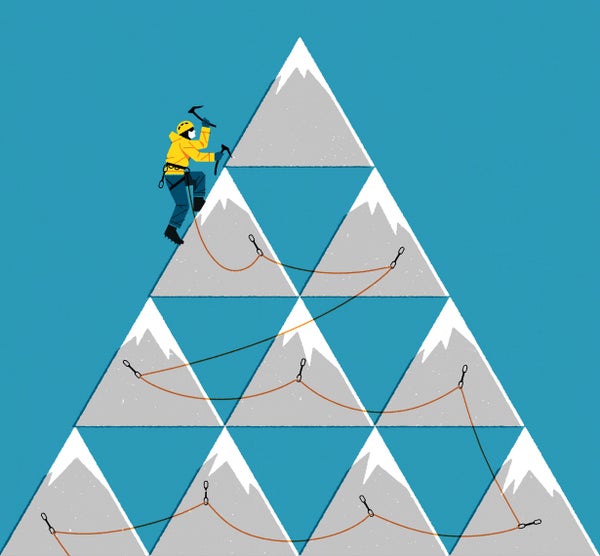

At first glance, breaking down a bigger goal into smaller pieces might seem like a superficial “reframing trick.” In actuality, it is a versatile goal-setting strategy that you can apply to almost any target—whether it’s learning a second language, picking up a new skill at work, starting an exercise regimen or saving for retirement. But how certain are scientists that this trick is effective? Through a large, multimonth field experiment, we were able to confirm the power of this technique—which validates much older research with contemporary scientific standards.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In the 1970s Albert Bandura and other psychologists conducted a series of pioneering studies with small populations of students and community members. Their findings suggested there were benefits to breaking an ambitious target into small “subgoals.” Since that time, surprisingly little research has explored this approach. In particular, there has been a lack of experimental research using large sample sizes, naturalistic settings (that is, where people are going about their daily life) and prespecified analysis plans. Our team conducted a massive new field experiment with state-of-the-art methods to assess whether breaking big goals up really can meaningfully improve outcomes. We published our findings in the Journal of Applied Psychology, and our results offer several insights for tackling your goals.

For our study, we partnered with Crisis Text Line (CTL), a nonprofit organization that provides free crisis counseling via text message. All CTL volunteers are asked to commit to 200 hours of counseling work within a year of finishing a lengthy training program for crisis counselors. This target is fairly ambitious, given that Americans clock less than 70 hours a year on average with organizations where they formally volunteer. We were curious about whether breaking down this big, 200-hour goal could make it more approachable for people and increase the number of hours they worked.

In our experiment, more than 9,000 CTL volunteers received e-mails every other week for three months. We randomly assigned them to e-mail lists with different descriptions of the 200-hour yearly commitment. One group was encouraged to hit the 200-hour mark by volunteering “some hours every week,” with no detailed goal breakdown. Two other groups were given clear subgoals: we encouraged one to volunteer for four hours per week and the other to volunteer for eight hours every two weeks (both approaches added up to 200 hours a year). Then we tracked how much time each group of trained crisis counselors actually spent volunteering during our three-month study.

Breaking down big goals into more manageable chunks had a meaningful and sustained impact on volunteering. People who were encouraged to focus on a smaller subgoal (volunteering four hours a week or eight hours every two weeks) volunteered 7 to 8 percent more than their peers who were simply asked to hit their big goal with a little work each week. This may sound like a modest increase, but when scaled across CTL’s thousands of volunteers, our intervention translated to thousands of additional counseling hours every month at essentially zero cost to the organization.

We also found suggestive evidence that the more flexible “eight hours every two weeks” framing led to more durable benefits over time. Although volunteering declined across all participants each week during the 12-week experiment, this decline was slower in the “eight hours every two weeks” condition than in the stricter “four hours every week” condition. This finding suggests that making modest goals flexible may encourage more long-term perseverance.

Our study dovetails with research by behavioral scientists Hal Hershfield and Shlomo Benartzi, both at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Steven Shu of Cornell University. Their work shows that people are four times more likely to sign up for a savings program when the required deposit is described as $5 a day rather than (the equivalent) $150 a month. Hershfield and his colleagues theorized that people may find it less painful to make frequent but small payments than they would to give up an equivalent, large lump sum. Similarly, we believe part of why subgoals motivate people is that these objectives make them focus on committing small bits of time or money to their goal in the near future, which is less daunting than making equivalent but larger and longer-term commitments. Taken together, this recent research suggests that whether goals require taking a single action or “keeping your nose to the grindstone,” subgoals may help.

So don’t plan to run 365 miles this year; aim for seven miles a week. And instead of promising to commit 200 hours to a goal in a year, mark four hours a week or eight every two weeks on your calendar. As for Milkman, after 365 practice days, lo and behold, becoming bilingual is at last on the horizon for her.

Are you a scientist who specializes in neuroscience, cognitive science or psychology? And have you read a recent peer-reviewed paper that you would like to write about for Mind Matters? Please send suggestions to Scientific American’s Mind Matters editor Daisy Yuhas at dyuhas@sciam.com.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.