The recent discovery of several hundred children’s remains in unmarked graves at residential schools for Indigenous children in Canada has highlighted similar suffering in over 350 such schools in the U.S., which are only now being investigated. The causes of so many deaths—of 4,120 children identified by Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, with many more unidentified—included tuberculosis and other diseases, but cruel patterns of corporal punishment and sexual abuse also played a major role. Children’s separation from their families was brutal, involving a policy of assimilation that served to undermine Native American resistance to dispossession. Carlisle Indian Industrial School, near Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania, served as the model for both countries. In July 2021, nine Lakota children who died there were reburied with honor by their people; another child’s remains were returned to her Alaskan Aleut tribe.

The worldwide dissemination of Canada’s somber news has shone a spotlight on similar abuses in schools in many countries. One is India, which has more than 100 million tribal citizens. Researchers have uncovered considerable evidence of physical and sexual violence and poorly explained deaths of children in India’s schools and hostels for Indigenous children. Such abuse is integral to a rarely-spelled-out policy of assimilation into mainstream society, which, like the North American ideology, rests on paradigms of social Darwinism and cultural racism. Assimilation requires the systematic denigration of Indigenous cultures and languages, implemented through seemingly benevolent and “civilizing” education. A key driver of such erasure is an invasion of mining companies into tribal areas, which leads to huge takeovers of land that replicates the seizure of countless Native American territories.

Many of India’s indigenous inhabitants call themselves Adivasis, or “original dwellers.” Officially described as members of over 700 “Scheduled Tribes,” they comprise 8.6 per cent of India’s population. Many of these peoples preserve distinctive cultures, cosmovisions (knowledge and value systems at the heart of Indigenous ways of life) and languages, despite relentless dispossession by mining-based industrialization and the exclusion of tribal languages from school and college curricula. Although India’s Constitution gives every child the right to be taught in their mother tongue, few of these ancient languages are in fact allowed to be spoken at school. Moreover, at least 20 million Adivasis have been evicted from their land, forest and traditions by big dams and mining projects—an enormous impoverishment in the name of development. Many Adivasi communities have resisted mining takeovers effectively

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

, but boarding schools often undermine their struggles.

Although no official estimate exists, India’s tribal residential schools number at least 7,000. Their social and psychological impacts are little understood, but cultural racism is institutionalized and abuse frequent, with girls facing sexual exploitation that is regularly masked by corrupt power structures. The deaths of 882 tribal children were reported for state-run schools across the country from 2010 to 2015, from varied and often poorly documented causes; over 1,000 deaths were recorded in the state of Maharashtra alone over a 15-year period. Cases of adults in charge of hostels and schools being found guilty of rape or sexual abuse of children have been reported from Telangana, Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra and Odisha among other states. The atrocities exposed in the media are, however, the tip of an iceberg, and few perpetrators have been properly punished. Sexual abuse is far more widespread than is generally acknowledged.

Other similarities with the North American schools are also apparent, including corporal punishment and tuberculosis and other diseases spread by overcrowding in dormitories. Hair being cut short upon enrollment is another striking parallel, as is an alienation of names. Christian missionaries set up the first schools for tribal children in India, and some schools are still run by Christian foundations. From the 1920s onward, however, ashram schools based on Hindutva, or Hindu nationalist, ideology were promoted. The Hindutva schools arose as a reaction to the missionaries, but the underlying “civilizing mission” that considers tribal culture to be “backward” is very similar. These schools frequently impose Hindu names on Adivasi children when they enroll, replacing their original names—just as Native American names were regularly erased or Christianized at North American schools.

One key difference from North America, however, is that tribal children in India are not coerced into residential schools. Instead, pro-corporate government policies evict them from their fields and forests and simultaneously render small-scale farming unremunerative (for those who still have access to some land), reducing many Adivasi families to desperate poverty. This dispossession makes most Adivasi parents eager to give their children a formal education to help them get decent jobs, even if it means alienation from traditional land-based skills. Long-standing racism—many Adivasis are mocked throughout their lives for being different—increases their readiness to accept the loss of culture and language.

Police also often play a key role in sending tribal children to residential schools, particularly in communities where Maoist militants are active. Since India’s liberalization in the 1990s, the nation-state has worked closely with mining companies to evict Adivasis from forests and fields in mineral-rich states such as Chattisgarh, Odisha and Jharkhand, sparking a resurgence in Maoist activity. A 2013 study by Save The Children

, as well as our own research, reveals that hundreds of tribal children had to stop attending village schools when security forces occupied them. Several thousand other day schools have also been closed, and a new generation of much larger residential schools has been promoted instead—often funded by the very mining companies that are taking over Adivasi lands.

Extraction Education

In other words, India’s tribal children have been increasingly extracted from their land and communities by large residential schools set up and funded in coordination with the mining companies that are seeking Adivasi lands for their mines and metal factories. This phenomenon has been termed extraction education in Canada and is particularly applicable to the Indian context.

The world’s biggest residential school is Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences (KISS) in Odisha, whose tribal students number at least 27,000. KISS promises hope and literacy for thousands of “first generation learners”—the phrase demonstrating its premise that Adivasi educational systems impart no knowledge of consequence. KISS works closely with the mining companies whose appropriation of Adivasi lands is being widely resisted by the very communities from which the schoolchildren are drawn. As such, the school threatens cultural breakdown, reproducing the separation of children from their land and traditions so starkly apparent in the phrase “Kill the Indian, Save the Man

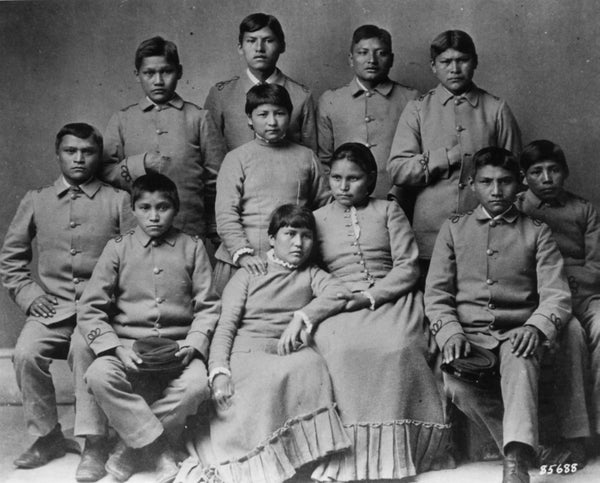

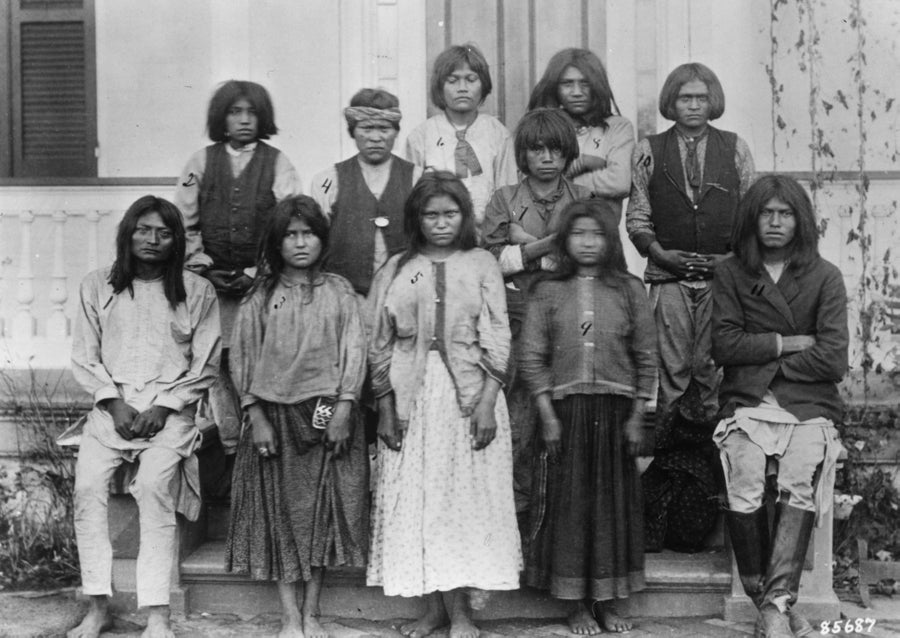

Geronimo of the Chiricahua Apache tribe surrendered to U.S. troops in September 1886, marking the end of the Apache wars. His band was taken prisoner and many of the children were transported to the Carlisle school, being photographed upon arrival for the “before” portrait. Credit: John N. Choate Getty Images

” that spread from the Carlisle school.

There is another similarity between the North American and the Indian residential schools. While they were operating, the North American schools were seen as “civilizing” native children and giving them a positive future through education. The abuse was everywhere, yet invisible, in that few people in the conquering society commented on it publicly. Similarly, in India now, large residential schools are seen as “mainstreaming” tribal children and raising their literacy rates. When sexual abuse and unexplained deaths emerge into view, these are portrayed as occasional aberrations, rather than symptoms of a systemic malaise. The suffering is ignored.

There is one difference, however: assimilation was the declared policy in the U.S. and Canada until the final decades of the 20th century, whereas India’s tribal policy was advertised as integration—encouraging Indigenous languages, skills and pedagogies while providing access to “modern” forms of knowledge. In practice however, the policy has been one of undeclared assimilation, as evident from a 2014 tribal policy report.

Produced by a committee chaired by sociologist Virginius Xaxa, this government report represents a landmark in recognizing the extent of repression that Adivasis face. It was predictably sidelined when it came out. Indian anthropology has rarely emphasized India’s covert assimilationism and the role played by tribal schools; on the contrary, as Xaxa has noted, it played a role in legitimizing KISS as a venue for the 2023 World Anthropology Congress, thereby supporting an agenda of assimilation or “mainstreaming.” Xaxa has come under attack for this observation. The decision of having KISS as venue was overturned in mid-2020, after a petition highlighted the iniquity of holding an anthropology congress in a huge tribal boarding school. Rarely, if ever, has the venue for a major conference become more contentious.

This dispute raises disturbing questions about the complicity of anthropologists in the cultural genocide that continues through schooling. Anthropology was originally a colonial discipline, which emerged to help colonizers comprehend and control the peoples whose lands they were conquering. In India, it still often appears to impart “scientific knowledge” about tribal peoples to the general public through museums and publications that depict them, for example, through life-size manikins that reinforce stereotypes about “primitiveness.”

The cultural racism that permeates many tribal schools in India disdains Adivasis as “backward Hindus” and, in recent decades, imposes an ideology of Hindu nationalism. Throughout India, over 50,000 tribal schools have been set up by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the Hindu nationalist organization steering present government policy, and many tribal children from Northeast India have been “trafficked” to its fundamentalist schools in other parts of the country.

Decolonizing Knowledge Systems

Boarding schools for Indigenous children that devalue and attempt to assimilate their cultures have roots going back several hundred years in Latin America. Such schools continued there up to the mid-20th century—among the Shuar, for example, who are now at the forefront of decolonizing education in Ecuador—as also in New Zealand and Australia.

Such schools still operate in a number of countries, though nowhere on the same scale as in India. From some, children are running away, or trying to, as happened so often from North American and Australian boarding schools. In 2015 for example, in mainland Malaysia, five children of the Orang Asli tribe died after getting lost in remote forest; they had run away from a boarding school where Islamic values were instilled with violence. Their parents were not even allowed to help in the search.

Schooling as brainwashing or indoctrination is well-known among Tibetans and Uighur in China, and Kurdish children in Turkey. Less well-known is the neglect and systematic indoctrination of Indigenous children in West Papua and other parts of Indonesia; though a network of Indigenous-run schools is starting to transform the institutionalized racism there. In 2017, President Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines threatened to bomb schools of the Lumad Indigenous people, blaming these schools—where Indigenous values and languages are being taught—for spreading insurgency.

In India, a number of schools are starting to “reverse the learning,” making use of Indigenous languages and knowledge systems, albeit on a small scale. Muskaan and Adharshila (both in Madhya Pradesh, central India) are just two of these. The endeavor represents a beginning for cognitive justice—a necessary counterpart to the self-determination, sovereignty and autonomy enshrined in the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as well as much Indian legislation.

Given the invisibility of the daily suffering of countless Indigenous children in India, including its lack of acknowledgement by the Indian state, how can the abuse be healed? In Canada, a start has been made–for all its shortcomings—through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Only through recognizing and calling out the abuse is there any hope of real healing. Surely it is time for the Indian state to initiate a similar process.

Both anthropology and tribal education in India, as in other postcolonial nations, are in urgent need of decolonization to this day. Reexamining and rejecting deep-rooted prejudices is necessary to free and honor communities that have survived in the face of extreme threats, and may yet play a vital role in teaching us how to share resources more equitably.