Jupiter has been taking a beating lately.

In September and October, observers spotted two different asteroids slamming into the massive planet just a month apart. While it’s not the first time observers have caught such a spectacle, successfully spotting an impact is fairly rare, and can tell us more about the solar system as a whole. And there’s the thrill of knowing a piece of the universe has just exploded in the atmosphere of the solar system’s largest planet.

“These fireballs are very rare, they are very difficult to be observed just by chance,” Ricardo Hueso, an astronomer at the University of the Basque Country in Spain who has studied these sightings, told Space.com. “This year has been exceptional because normally we discover one of these impacts every two years approximately.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Hit after hit

Despite the rarity, the odds of seeing an impact at Jupiter are higher than anywhere else in the solar system, thanks to the planet’s enormity. Jupiter is both the largest target to hit and the most powerful gravitational tug in the neighborhood besides the sun itself, increasing its impact rate in comparison with smaller worlds.

Many of these impacts are spotted by amateur astronomers. Professionals usually can’t arrange to use high-powered telescopes for the large chunks of time necessary for such serendipitous observations, and the flashes are visible in even small telescope.

Nevertheless, the most recently spotted impact was in part discovered by a professional astronomer, Ko Arimatsu of Kyoto University in Japan, who often has a telescope trained on Jupiter. “When I found the impact flash event through my detection program, I was astounded,” Arimatsu told Space.com in an email. “The quick finding indicates that I was lucky, or the impact rate is much larger than previously expected.”

Arimatsu was also able to observe the event in two different wavelengths, giving scientists more information about the energy released and the mass of the impactor, Hueso noted. That’s a more detailed observation than amateurs are usually able to contribute.

But other observations were still more serendipitous. NASA’s Juno mission, which has been orbiting Jupiter since 2016, happened to fly over the very spot of the impact just 28 hours later, Hueso said, and its camera snapped a picture of the patch of atmosphere in question from a bit over 1,200 miles (2,000 kilometers) above the clouds.

“In that image we don’t see any trace in the atmosphere,” Hueso said. “So again this is an object small enough that anything that was released in the atmosphere of Jupiter has dissipated and diffused in the atmosphere by the environmental winds in a matter of a few hours.”

The September impact was also exceptional for more than the close timing, Hueso said. It was also observed by the most people for such an event, and was the brightest fireball flash observed at Jupiter to date.

“Probably it’s the largest object that we have seen impacting the planet and producing a fireball that’s not large enough to leave anything visible in the planet later on in the next hours or days,” he said, suggesting that the object was a few tens of meters across.

As scientists try to spot smaller and smaller objects in the solar system, their targets become more difficult to observe; the same holds true when objects are farther away. So when it comes to objects just dozens of meters wide that are out around Jupiter’s orbit, which is always at least 350 million miles (560 million km) from Earth, scientists are simply out of luck to spot them directly.

“Since it is impossible to directly observe meter-size objects beyond the main belt, their number is unknown,” Arimatsu said. “Jupiter is a natural ‘detector’ for such tiny objects, and the occurrence rate and brightness of the impact flashes are crucial to understanding their size and number density.”

It’s difficult even to say how many there are to see. “We don’t really know how many millions of objects of this size exist in the solar system but we are talking here about tens of millions or hundreds of millions of objects of this size,” Hueso said.

Clocking impacts at Jupiter, though, can help. Right now, Hueso estimates that at an absolute minimum, about 20 objects hit Jupiter every year—but of course, that includes objects that hit the far side or the poles, where even the most careful survey couldn’t see the flash. Still, the flashes that mark the demise of those space rocks are one of scientists’ few ways to study the smallest of asteroids.

“This is the only way that we have to observe these objects,” Hueso said. “Either we observe them when they impact an object, and they create a crater on Mars for instance, or a flash of light on Jupiter, or when they come very, very close to the Earth.”

Leaving a mark

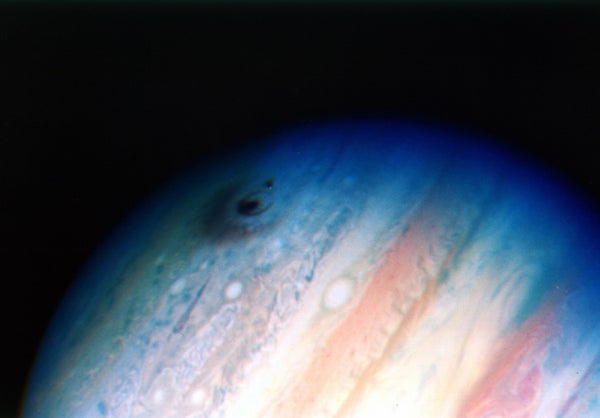

The best-known impact at Jupiter was that of the 19 fragments of a comet called Shoemaker-Levy 9 in 1994. Scientists discovered the object early enough to see the planet’s massive gravity tear it apart and watch the fragments meet their fate.

“I remember that the very first time I connected to the internet, it was to look for images of the comet that was going to collide with Jupiter,” Hueso said.

Even as the pieces of Shoemaker-Levy 9 reshaped the astronomy community, they also left their mark on Jupiter itself, leaving in its clouds a dark splotch larger than Earth that was visible for months. The darkness was a sign of where debris from the comet fragments’ atmospheric explosions slowly dissipated, mixing into the outer layers of clouds.

For Hueso, that trace is one of the key reasons to be interested in impacts at Jupiter. “These objects have been impacting the planet Jupiter for the last hundreds of millions of years,” he said, “they are bringing different types of material to the atmosphere of Jupiter, in some sense they are contaminating the atmosphere of Jupiter.”

But it’s a rare impact that leaves such a glaring scar. Shoemaker-Levy 9 is still the most dramatic impact scientists have seen at Jupiter, and one of very few that left observable traces within a few hours of the collision. Since then, scientists have only spotted smaller objects meeting their end in the behemoth’s clouds, and they haven’t seen a scar since 2009, even with the compelling new observations.

“That was the last time. All the different impactors we’ve discovered since then, none of them have left any trace visible in the atmosphere,” Hueso said. “Not from the Earth at least.”

Copyright 2021 Space.com, a Future company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.