- Science News

- Featured news

- Secret role of swallowing in conversations revealed by new research

Secret role of swallowing in conversations revealed by new research

By Dr Richard Ogden, University of York

Image: fizkes/Shutterstock

Richard Ogden is professor of linguistics at the University of York, where he is a member of the Department of Language & Linguistic Science, and of the Centre for Advanced Studies in Language & Communication. His work combines studies of phonetic detail with conversation analysis. He has published on turn-taking in Finnish, assessments, complaints, offers, and more recently has been working on click sounds ('tut', 'tsk') in English. Now, he explains how a seemingly simple act like swallowing plays an important role in our how we communicate.

What does swallowing tell us about language? There’s a surprising amount. One is that swallowing is tightly interwoven with the structures of language and speech: the positioning of swallows displays a sensitivity to syntactic and prosodic structures in talk.

Another is that we interpret swallows as places where speech is temporarily not possible, because swallowing makes the vocal tract unavailable for talking. The tightly closed lips, co-occurring facial expressions and audible features like the clicks made on the release of the swallow can all be recruited to signal something about whether talk will continue or not; and in some cases, what kind of talk is ongoing.

Swallowing is probably labelled as a form of silence in many studies of speech.

Like breathing, swallowing is a somatic function which mostly goes unnoticed.

What happens when we swallow?

Swallowing is a complex physical process and is at the boundary between speech and the body; yet we know very little about how swallowing and speaking work together in everyday interaction.

Swallowing is the process of moving a ball of food or liquid (bolus) from the mouth to the oesophagus and then into the stomach. The action of swallowing is incompatible with speaking, because the closures at the lips, glottis (middle part of the larynx) and velum (soft palate) mean that the vocal tract is temporarily sealed off, and the airflow required for speech is not possible.

Like breathing, swallowing is a somatic function which mostly goes unnoticed. Not all in- or exhalations are audible; and not every swallow is audible or visible either.

Swallowing can produce some very quiet sounds which can be picked up with strategically placed microphones. Swallowing is also often visible.

When swallowing, a speaker often presses their lips tightly together, the ascent and descent of the larynx might be visible, along with head movements which straighten out the pharynx (part of the throat behind the mouth and nasal cavity).

In my recent study published in Frontiers in Communication under the research topic The Grammar-Body Interface in Social Interaction, I focused on moments in talk-in-interaction where swallowing is either noticeably (which is not to say deliberately) visible or audible, or both. So, while swallowing is not a very noisy event, it is one which a co-participant in conversation is likely to be able to observe. How do we integrate swallows with talk? And what does this integration tell us about language?

Dr Richard Ogden. Image: Richard Ogden

Download original article (pdf)

The functions of swallowing in conversation

Swallows occur in several positions in talk.

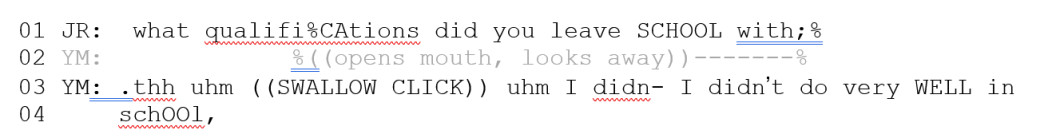

Swallows can occur before a turn at talk; and in this position, swallowing goes around with other physical preparations for talking, like breathing in, adjusting the posture, and separating the articulators from a resting position. Here’s an example:

This swallow is one of several devices – like the ‘uhm’ and the inbreath (.thh) – that delay the answer to the question, and that is partly how YM presents his answer as being not the best kind of answer one could give to this question.

Swallows are also found at the ends of turns at talk. These swallows usually involve very tight lip closure which is noticeable at the end of words.

For example, ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and swallow often comes out as a form of ‘yep’ or ‘nope’, although usually we get the closure for the [p], but not the release (ie the lips don’t open again, which can be understood as indexing ‘no more to say`).

Swallows can also be found within turns at talk. In these cases, the talk is suspended in various ways before the swallow, and then picked up again after the swallow. The details of this are quite subtle, and depend on the kind of thing that is being done at the time. For example, swallowing is common during word searches, as in “Belinda got-uhm swallow + click a grant”. In structures like these, the particle ‘uhm’ marks the temporary suspension of the talk; the ‘uhm’ appears at a place where the syntax is not complete and its intonation (long and level) projects that more talk is coming; the click (‘tut’ or ‘tsk’ sound) is the audible release of the swallow.

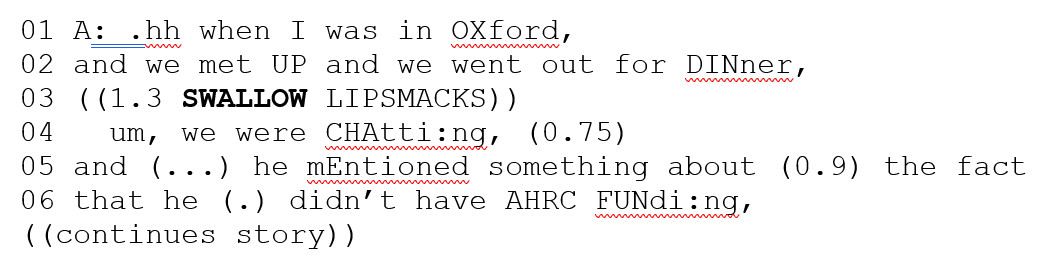

Swallows can also be placed at syntactic and prosodic boundaries as in this case:

In this example, the swallow is placed at a syntactic and prosodic boundary between two clauses within a multi-clause sentence. The “when” clause which starts at line 01, is extended with two “and” conjunctions in line 02, projects a main clause which has not yet been produced at line 03 when the swallow occurs. If swallowing is a somatic requirement, then timing it so that it falls at a clause boundary means that it is less exposed in the interaction than if embedded within a lower-level constituent such as between ‘we’ and ‘went’ or ‘went’ and ‘out’. A’s coparticipant does not treat the silence with the swallow at line 3 as a place to come in: they leave A to continue talking.

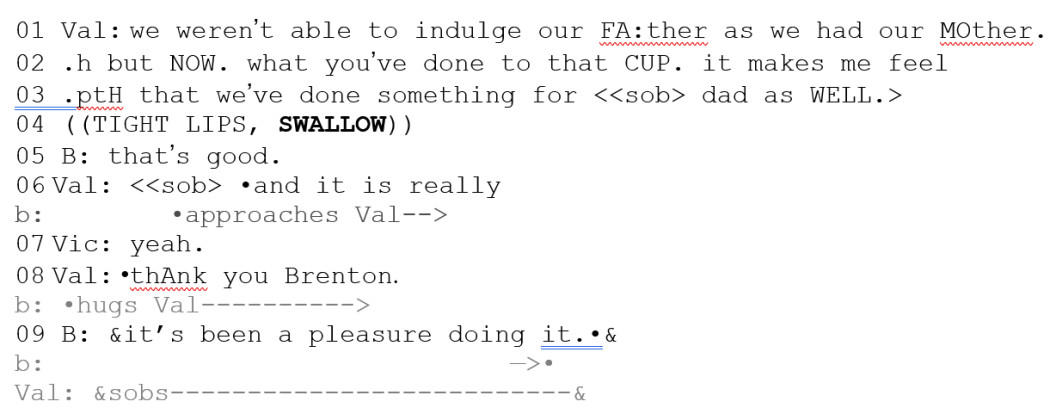

Finally, swallowing is connected with affective displays, which include crying and sobbing and facial expressions that display ‘trouble’. Sobbing or crying occur sometimes before, sometimes after the swallow. Because of its association with crying, swallowing can be recruited as part of a display of a heightened affective stance, and sometimes the inability of a speaker to find the right words – swallowing can be one way to display `lost for words’.

In this example, Val is having a cup returned to her which has been mended, and she is reminiscing about her father, and what the repair means to her. As she talks, she starts sobbing; her turn at talk ends with a swallow and B(renton), the repairer, goes to hug her.

Hopes for future research

My hope is that this work will be valuable, for example, in speech and language therapists in understanding how swallowing works in typical speech; and for linguists who want to understand what more about how language is connected to the bodies we inhabit.

If you have recently published a research paper with Frontiers and would like to write an editorial about your research, get in touch with the Science Communications team at press@frontiersin.org with ‘guest editorial’ in your subject line.