By Molly Bogeberg, Marine Conservation Manager

Pacific salmon (Chinook, chum, coho, pink, and sockeye) are an anadromous species. They start their lives in freshwater, migrate to the ocean for most of their lives, and then return to freshwater rivers and streams to spawn and die. Before salmon enter the ocean, they must find clean and cold waters to forage and grow. As young salmon (called smolts) move down streams or rivers towards the ocean, they pay a visit to an estuary for 1-3 months. Estuaries serve as critical habitat where smolts adjust to saltier water and search for tasty plankton, insects, and other small prey. Estuaries that have lush marsh vegetation and deep, cold, branching channels make prime habitat for these young salmon.

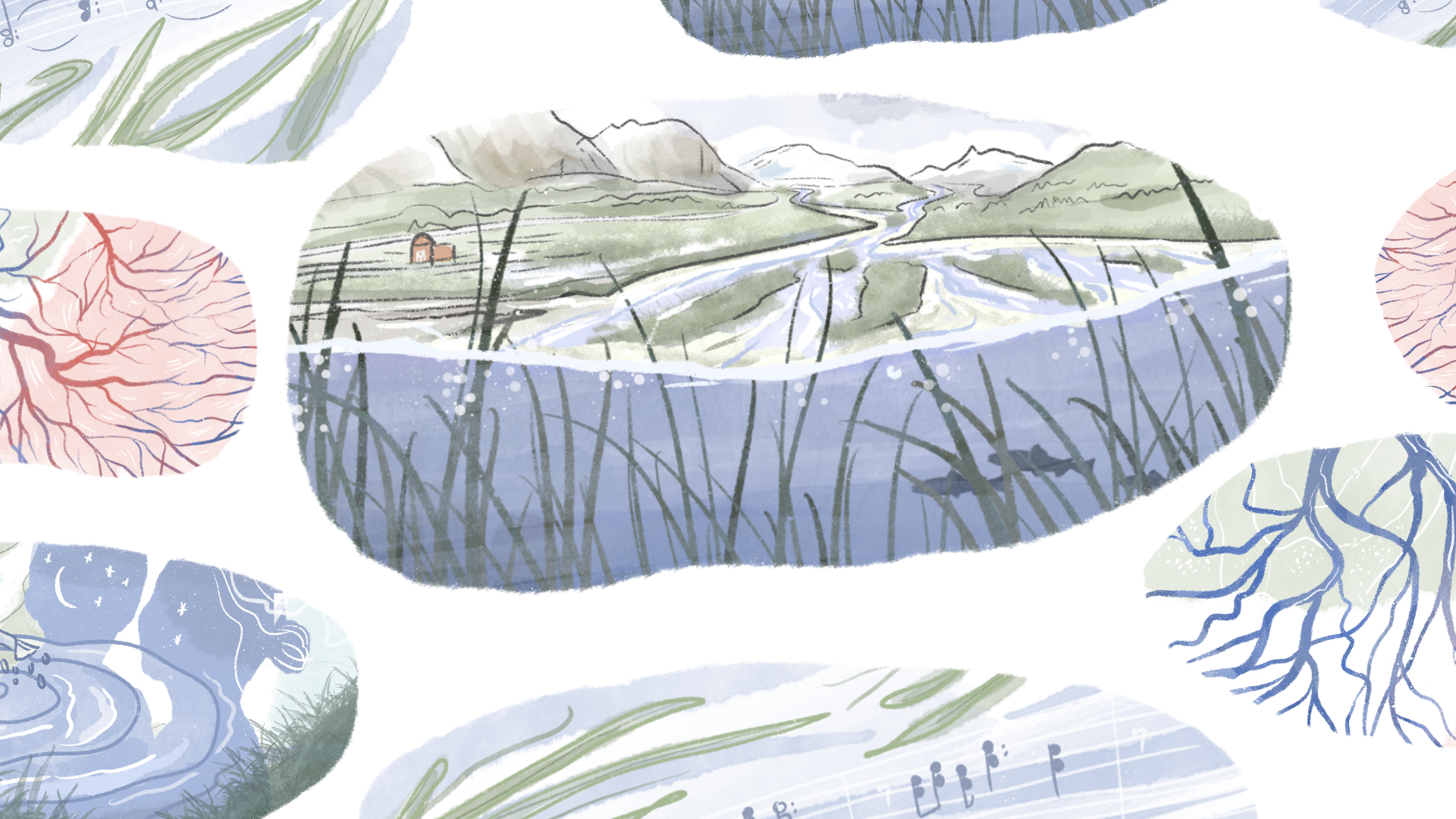

AN ESTUARY CHANNEL surrounded by bulrush marsh plants that collect and trap insects, a favorite prey item of salmon smolts. ©Molly Bogeberg

At the mouth of the Stillaguamish River lies TNC’s Port Susan Bay Estuary Preserve. Before TNC purchased the property, 150 acres of the preserve had been converted to agricultural land. In 2012, TNC re-connected the land to the tides, forming brackish estuary habitat once again. Today, the restoration site provides important habitat for invertebrates, birds, fish, and a diversity of marsh plants. After five years of monitoring, however, we know more restoration work is needed at the site. Digging a connected network of channels will help fish to access the site, improve fresh and saltwater flow, and allow marsh vegetation to thrive.

Chinook stocks in the Stillaguamish River are some of the weakest in the Puget Sound, which has resulted in fishery closures in the Sound as well as in the Gulf of Alaska. At the same time, it is likely that fish from the Skagit and Snohomish Rivers spillover to Stillaguamish estuaries as well. Therefore, bolstering the estuary habitat that we do have for salmon smolts in the Stillaguamish Delta is critical. Since 2017, TNC has been working with engineers, technical experts, and stakeholders to design another stage of restoration at the Port Susan Bay preserve to optimize the habitat’s function.

BRIAN HENRICHS (SRSC) measures a fish caught in a seine net. ©Molly Bogeberg

To measure the restoration’s success in increasing salmon access to the site, we’ve partnered with the Skagit River Systems Cooperative(SRSC)(who provides natural resource services for the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe and the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community) to monitor fish populations at our site before and after another stage of restoration. This summer, SRSC conducted fish seines at 15 sites inside and outside of the restoration zone every two weeks from February-mid-August. SRSC is also supporting a larger scale monitoring effort with the Stillaguamish Tribe and WDFW to study fish populations at other nearby restoration and reference sites (at zis a ba and Leque) in Port Susan Bay. These two efforts will help us understand the impact of restoration at our site as well as the fish connectivity between estuaries in Port Susan Bay.

While climate change threatens salmon species in many ways, ensuring healthy estuary habitat is available for salmon now and into the future will provide resilience to a species that humans, orca, and forests depend on.

BONUS: VIDEO FROM THE FIELD - SRSC and TNC staff examining fish caught in a seine net. Fish species are identified, counted, and measured at each site. Underwater in the net are mostly Chinook salmon.

© video by Brian Henrichs (SRSC); thumbnail photo by Molly Bogeberg