Eighty-two million years—that’s how much lifetime the U.S.’s Black population lost because of premature deaths between 1999 and 2020, a new study shows.

The numbers are an alarming reminder of concerning gaps in health care—and they are not entirely surprising, according to experts on racial health disparity. The study’s authors say their findings should be a “call to action” for policymakers. “There’s no biological, intrinsic reason why people with darker skin should have shorter life spans,” says Harlan Krumholz, a study co-author and a cardiologist at Yale University. But because of the systemic racism that plagues American society, “the family you’re born into in this country can have devastating consequences.”

Data used in this research included people categorized as male and female and included both children and adults. For simplicity, the graphics below refer to all such individuals as “men” and “women.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

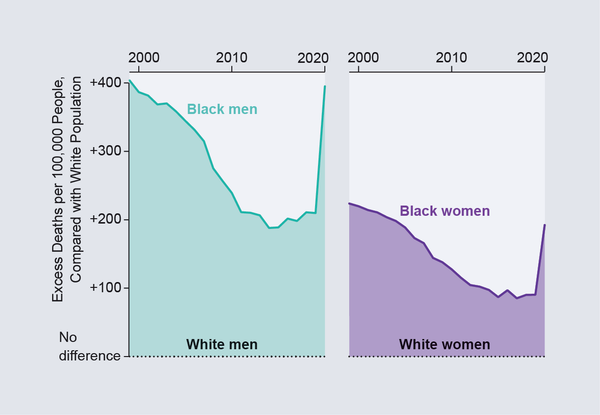

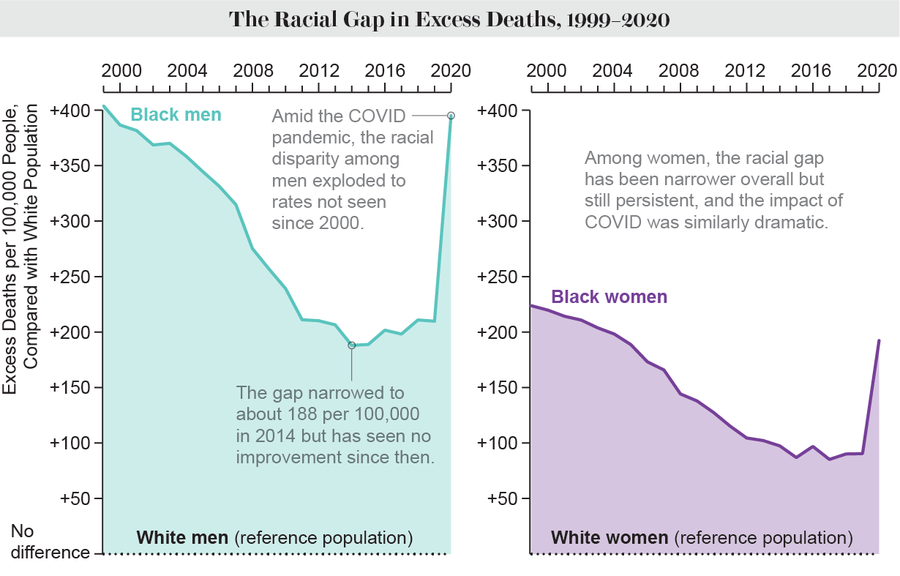

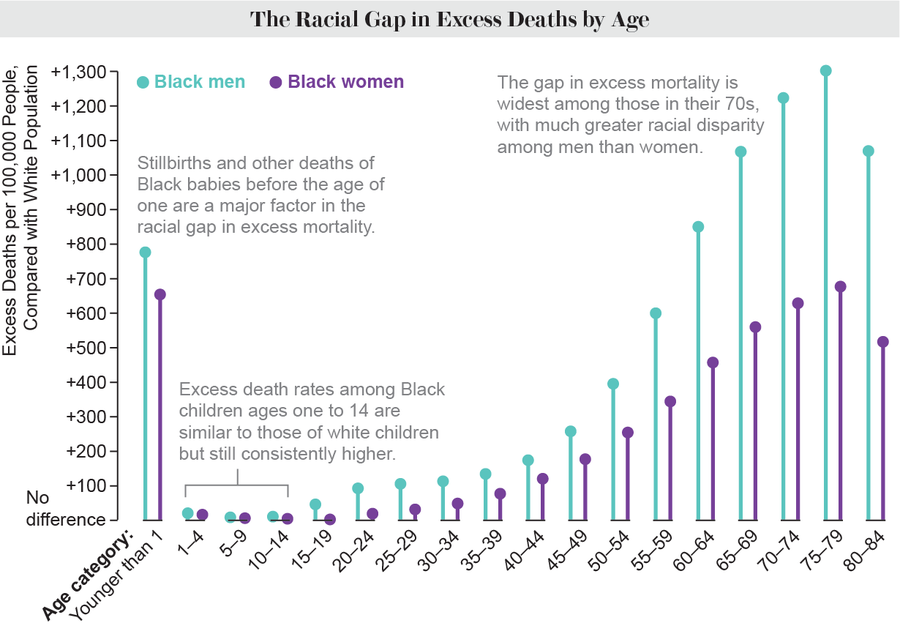

Fragile Improvements

Researchers often talk about health disparities between races as simply differences—vague phrasing that fails to communicate that such disparities should not exist, Krumholz says. Instead he and his colleagues discuss excess deaths: the number of deaths among Black people that exceed those among white people after accounting for differences in the age distribution and size of each community. Data from death certificates showed that 1.63 million more Black people died, compared with the white population, over the 22 years of the study, which was published last month in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

A handful of conditions, heart disease chief among them, caused many of these deaths. There are multiple reasons for this, says epidemiologist and internal medicine physician Lisa Cooper of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Equity, who did not work on the new study. For example, economic barriers often lead to Black people living in places where it’s difficult to access healthy food, space to exercise or adequate health care. And living in a racist society takes an additional toll on mental health. It’s “almost like a cascading effect” on overall health, Cooper says.

In the early 2000s heart disease began to drop in the Black population, and the overall health gap between Black and white people diminished. “Such a glorious time,” says demographer Kathleen Mullan Harris of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was not involved in the study. She links the decline to the fact that cholesterol and hypertension drugs—both of which reduce the risk of heart disease—started to become more widely available in Black communities. Improvements in cancer treatment also helped reduce mortality.

Progress was short-lived, however. Around 2011 the gap between Black and white excess deaths stabilized. “I think it really had to do with obesity,” Harris says. In the 1970s and 1980s heavily processed foods became cheap and plentiful in the U.S. A few decades later the effects were reflected in death rates. The same socioeconomic disadvantages that led to high rates of heart disease made the Black population especially vulnerable.

Then, in 2020, COVID hit the U.S., obliterating any progress on reducing health disparities over the past two decades. The disease was a leading cause of death among Black people, as it was in other marginalized populations. Indirect effects of the pandemic also exacerbated other health conditions: heart disease spiked again, for example. For the Black male population, deaths from assault also surged. The recent study does not address why assault rates increased in this population, but Cooper speculated that pandemic-related stress increased interpersonal violence, which was compounded by law enforcement systemically targeting Black men. “All of those things, I would venture to say, contributed,” she says.

Risks Early and Late

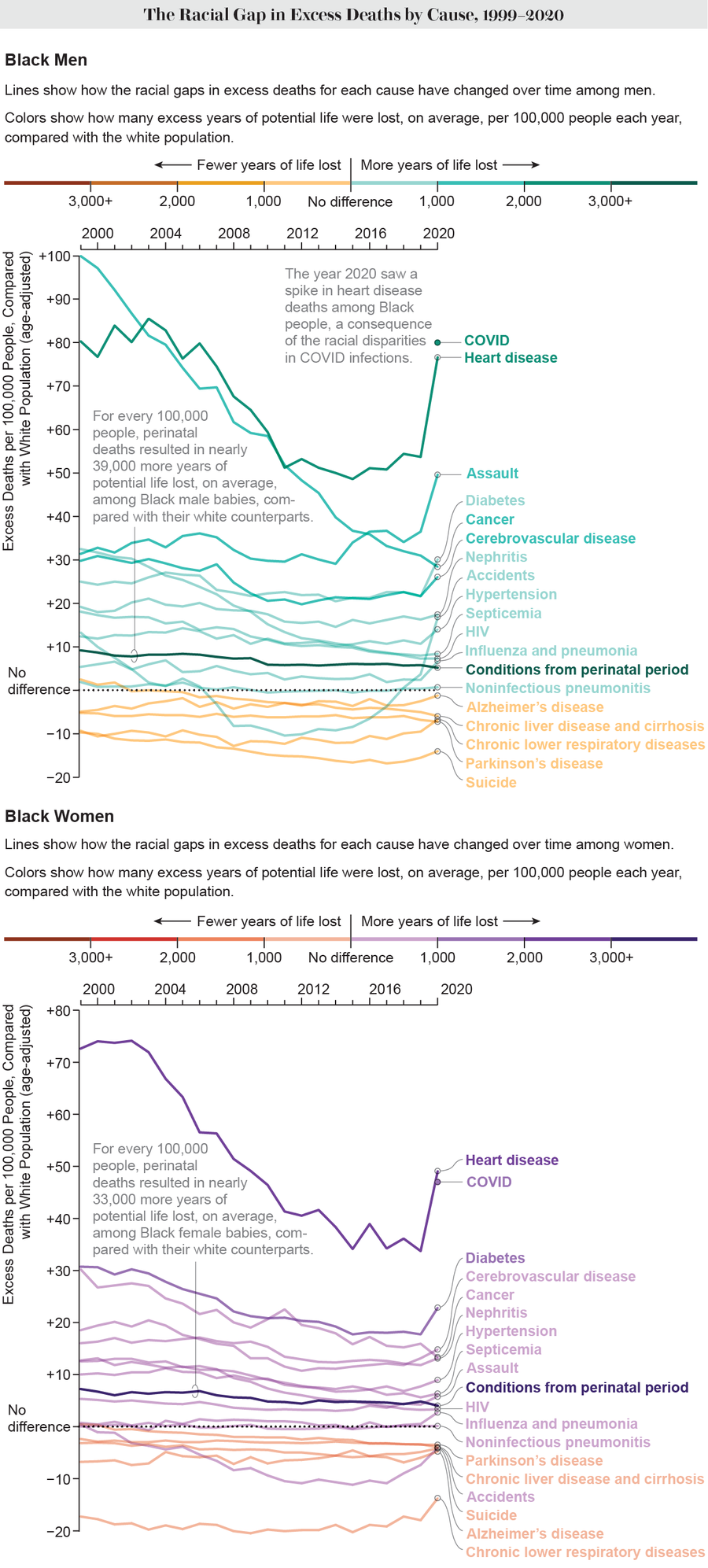

Relatively higher health risks among Black people start at an early age, Krumholz and his colleagues found. For every 100,000 children born, about 700 more Black kids die during their first year of life than white kids. The new findings are in line with previous research showing that Black babies tend to have lower birth weights than white babies for reasons researchers don’t yet understand, Harris says.

From ages one to 14, Black children have only a slightly higher chance of dying than white children. But excess deaths start to increase when Black kids are in their midteens, and the numbers continue to rise through adulthood.

Cooper draws on epidemiologist Arline Geronimus’s observation of “weathering,” which describes how Black people tend to age faster than white people. Over time, the combined effects of many chronic stresses—both physical and mental—simply wear many people down. “By the time you’re a teenager, you’re already obese; you’re already developing high blood pressure,” Cooper says. These stresses can lead to an early death.

Weathering can shorten a person’s life by decades, and even five or 10 years is a big loss. “It’s grandparents not at the table or older parents not around,” Krumholz says. “It’s tragic.”

How to Help

The scale of these disparities can make them feel “insurmountable and just impossible” to fix, Cooper says. Nevertheless, she and other researchers have some ideas for how to close the health gap.

Proposed solutions often focus solely on increasing Black people’s access to health care, but some causes of health disparities lie outside the doctor’s office, says senior policy analyst Latoya Hill of KFF, a nonprofit organization focused on health policy.* To create lasting change, she’d like to see policies that improve Black people’s abilities to find well-paying employment, access to education and housing in neighborhoods with lower pollution levels. “Housing sectors, economic sectors, employment sectors, education..., while health care does play a role, you really got to target those,” Hill says.

Three types of interventions could be particularly helpful, Cooper says. The first is improving opportunities in Black communities by raising the minimum wage and offering early childhood education, for example. The second is for health care providers to invest more energy in easing health problems before they turn into long-term conditions (for instance, programs aimed at reducing childhood obesity rates could prevent problems later in life). A third intervention would be encouraging key decision-makers to alleviate the health burden placed on Black communities. As a possible step toward this goal, employers could take action to better support employees if they realize poor health is preventing them from reaching their full potential. “When [Black] communities are hard hit, we all do worse,” Cooper says.

Without change, years of Black lives will continue to slip away. “Those are years people didn’t have friends and families and loved ones,” Krumholz says.

*Editor’s Note (6/6/23): This sentence was edited after posting to correct the current name of KFF.