There’s a common perception that cities are dangerous places to live, plagued by crime and disease—and that small towns and the countryside are generally safer and healthier. But data tell a different story.

According to a 2021 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report on mortality data from 1999 to 2019, people living in rural areas die at higher rates than those living in urban areas—and the gap has been widening. Rates for the top 10 causes of death in 2019 (including heart disease, cancer and accidents) were all higher in rural areas. And the pandemic has only exacerbated things: COVID is now the third leading cause of death nationwide, and rural areas account for a higher share of those deaths per capita than urban areas.

Compared with people living in cities, rural residents are less likely to have access to health care and more likely to live in poverty. Rural states and counties also tend to lean Republican, and many of them have resisted adopting public policies known to improve health.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“I’m not sure that many people are aware that death and health outcomes are deteriorating in rural areas relative to urban ones,” says Sally Curtin, a demographic/health statistician at the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) and a co-author of the report.

About 46 million people—15 percent of the U.S. population—live in a rural area, according to the NCHS. The center breaks down residential areas into six categories by level of urbanization, from most urban to most rural, based on the 2010 Census and other factors. For their analysis, Curtin and her colleague defined “urban” as a combination of the four most urban categories and “rural” as comprising the remaining two. They adjusted the death rates by age to account for differences in population demographics.

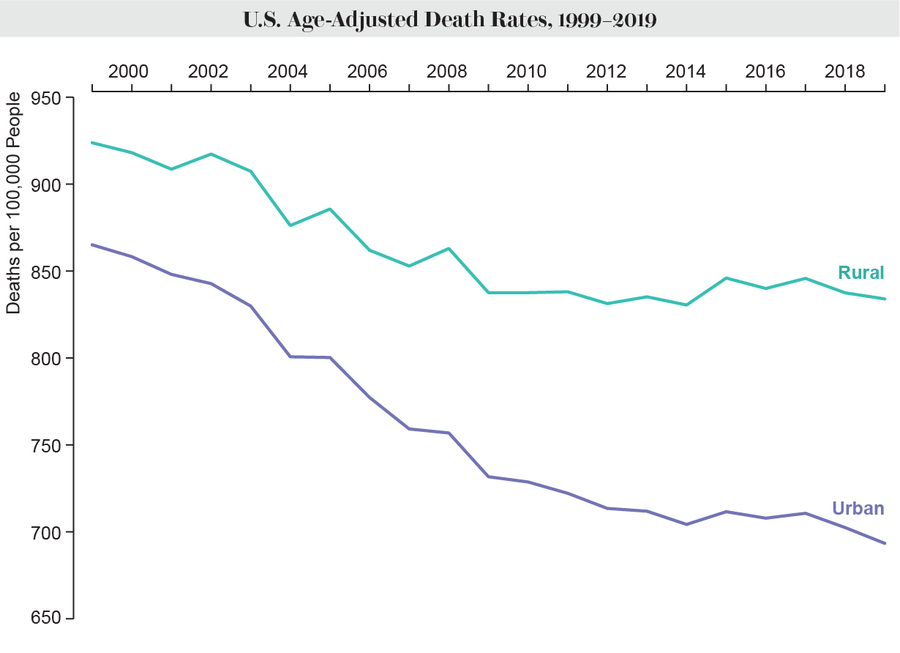

Mortality rates in both urban and rural areas fell from 1999 to 2019, but the urban rate started lower and fell faster, the data showed. The age-adjusted death rate in urban areas declined from 865 deaths per 100,000 to 693. In rural areas, it dropped from 924 to 834. In 1999 the death rate in rural areas was 7 percent higher than that in urban areas. By 2019, it was 20 percent higher.

A similar trend was seen for both men and women. While men have higher mortality rates than women overall, rates were higher among rural male and female individuals than among urban ones, and the gap widened over the study period, the researchers found.

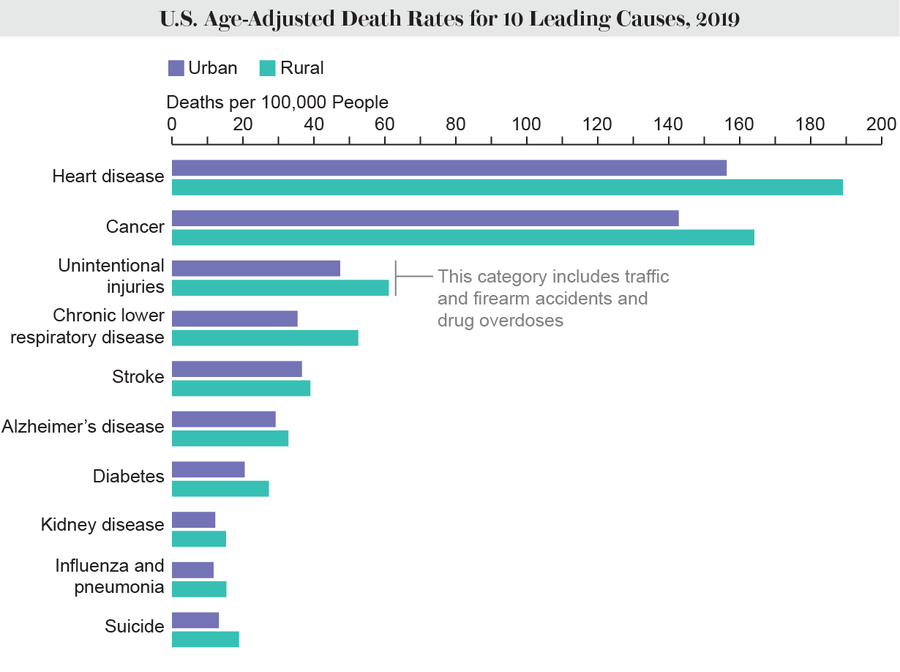

Mortality rates were higher in rural areas for all of the top 10 causes of death in 2019. Heart disease was the leading cause, killing 189 people per 100,000 in rural areas and 156 per 100,000 in urban ones. Cancer was the second-biggest killer, claiming 164 and 143 lives per 100,000 in rural versus urban areas, respectively. The third leading cause of death in 2019 was unintentional injuries, a category that includes causes such as drug overdoses and firearm injuries that exclude homicide and suicide.

Homicides are higher in urban areas, but overall gun deaths—most of which are deaths by suicide—are higher in rural areas, other NCHS data show. Rural deaths by suicide have increased by nearly 50 percent from 2000 to 2018, a separate analysis found.

The national opioid epidemic continues to worsen in both rural and urban areas. Close to 70,000 people in the country died of opioid overdoses in 2020. Although such overdose deaths are more common in urban areas, they are increasing at a faster rate in rural ones—which have fewer clinics and less access to treatment. In general, social isolation and economic challenges have made people living in rural areas especially vulnerable to so-called deaths of despair—those from overdoses, alcoholism and suicide.

Motor vehicle deaths are almost twice as common in rural areas as urban ones, according to another NCHS analysis.

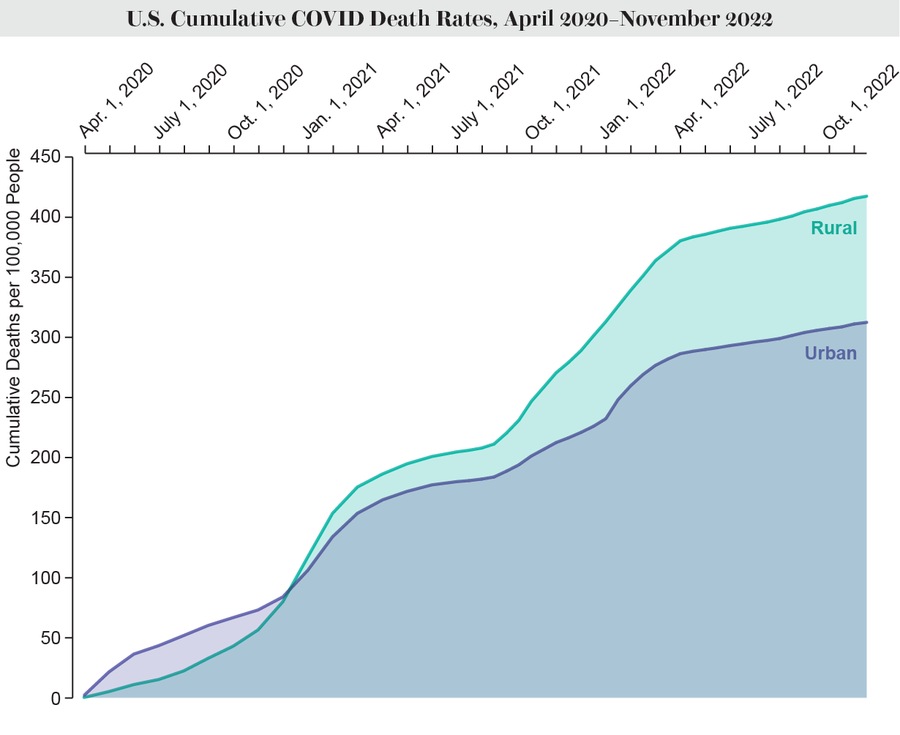

Since the NCHS study, COVID has overtaken accidental injuries as the U.S.’s third leading cause of death. In early 2020 the disease hit New York City and other Northeast cities especially hard. This cemented a perception that the virus that causes COVID was mostly spread in dense, urban areas, where people crowd together in subway cars and small apartments. But by late 2020, that was no longer accurate. Rural areas that had escaped the worst impacts of the first COVID wave began experiencing higher death rates than urban areas, and the gap has only gotten wider in the past year, according to an analysis by the University of Iowa’s Rural Policy Research Institute (RUPRI).

“In the early months [of the pandemic], there was some reinforcement of the stereotype that if you weren’t in the big city and in a crowded area, you didn’t have to worry so much about something like COVID,” says Keith Mueller, director of RUPRI and co-author of the analysis. As the death rates in rural areas caught up and later exceeded those in rural areas, “we were caught a little bit by surprise,” Mueller says. But against the backdrop of rural areas having worse health and higher mortality rates overall, it made sense. “If you’re more vulnerable generally, you’re definitely more vulnerable to the worst outcomes with something like COVID,” he says.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: “COVID-19 Cases and Deaths, Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Counties Over Time (Update),” by Fred Ullrich and Keith Mueller, in Rural Data Brief, No. 2020-9; Rural Policy Research Institute (RUPRI) Center for Rural Health Policy Analysis, December 2022

The reasons for the higher mortality rates in rural areas are likely multifactorial, experts say. “You can’t just point to one thing,” Curtin says.

Rural areas generally have less access to health care. There are fewer primary care facilities, and there may be just one easily accessible hospital—which could be an hour’s drive away or more. (Making matters worse, many rural hospitals have been forced to close in the past few years.) Compared with urban residents, people in rural areas are also more likely to be uninsured and have higher rates of poverty.

Higher rural mortality rates can partially be explained by behavioral factors that increase the risk of chronic disease, such as smoking and lack of exercise. Obesity rates are also higher in rural areas. But it’s often difficult to disentangle such behaviors from the politics and policy decisions that enable them.

“I 100 percent think there’s a political dimension to this,” says Haider Warraich, associate director of the Heart Failure Program at the VA Boston Healthcare System and an associate physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “Politics increasingly affects health in this country, more than any other country I can think about.”

Rural areas tend to be more politically conservative, and data suggest that people in Republican-leaning counties die at higher rates than people in Democratic ones. Many Republican-led states haven’t expanded Medicaid, which, under the Affordable Care Act, provides health insurance for low-income adults under age 65.“One policy we know has been shown to increase access to health care is Medicaid expansion, and unfortunately, many states with widest gap are ones where Medicaid was blocked,” Warraich says. States that lean Republican also have laxer regulation of smoking and other behaviors that lead to worse health outcomes, he says.

The COVID pandemic only amplified these trends as public health measures such as social distancing and vaccination became extremely politicized.

Warraich co-authored an analysis of the rural-urban gap in mortality rates from 1999 to 2019, broken down by age, sex and race or ethnicity. The data showed that non-Hispanic Black people had the highest mortality rate. But the group that showed the least improvement in mortality rates was white people. “The reason why this urban-rural disparity is growing at the rate that it is,” Warraich says, “is almost all because of the really dramatic slowdown in improvements in mortality in that group.”

Solutions do exist that could bridge the gap in urban and rural mortality. But these require buy-in from political leaders—to address not just access to health care but also other root causes of poor health.

“We need to be thinking about how you can reach people where they live, and how they live, to help them improve their healthy lifestyle,” Mueller says. Health care funding should be spent wisely in order to sustain services such as primary care and public health, he adds, so that when a situation like a pandemic occurs, the community is better prepared.

Warraich thinks rural public health should focus on issues for which there is some political consensus—such as tackling smoking, obesity and nutrition, and the opioid epidemic. “My hope is that the work that we’ve done, and that others have done, can start to be a wake-up call for lawmakers whose residents are mostly rural that they really are sitting on a public health crisis,” he says. “Inaction is just not an option.”