Some 465 million years ago, an armored pill-bug-like creature called a trilobite scuttled across an ancient seafloor and apparently scarfed up anything it could, according to a new analysis of its exceptionally preserved gut contents.

Thanks to their calcite-infused exoskeleton, trilobite fossils are routinely discovered around the world, revealing how these prehistoric seafarers saw their world and even how they had sex. But one major aspect of trilobites’ ecology that had long eluded researchers was their diet. Even the best-preserved trilobite fossils, which possess the ghostly imprint of a fossilized digestive tract, revealed frustratingly little about these critters’ menu.

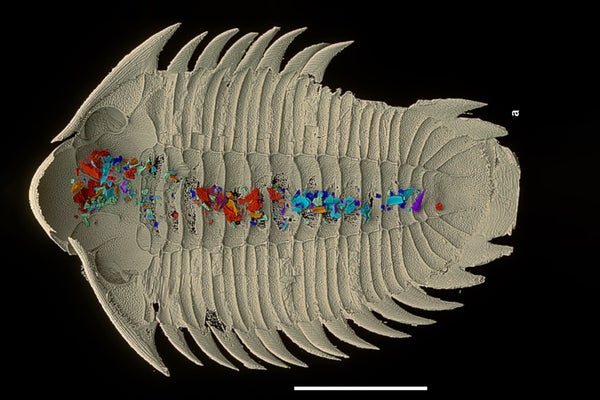

In the new research, published this week in Nature, a team of scientists used cutting-edge imaging techniques to peer inside a well-preserved fossil of the species Bohemolichas incola. The researchers discovered the trilobite’s nearly intact gut—the first of its kind in the fossil record—stuffed with the shelly remnants of an ancient seafood feast, revealing that B. incola was not a picky eater.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“This is the first example of actually being able to see what they were eating instead of just looking at the morphology and trying to infer what they could or couldn’t eat,” says Sarah Losso, a Harvard University invertebrate paleontologist, who wasn’t involved in the new study.

The trilobite specimen hails from a well-known fossil deposit near Prague. The area’s fossils, which are often preserved in three dimensions inside of nodules nicknamed Rockycany balls, offer a glimpse into a marine ecosystem that existed during the Middle Ordovician period between 470 million and 458 million years ago. When a local fossil hunter cracked into one of these nodules in 1908, they discovered the nearly intact trilobite entombed inside.

The stunning find ended up at a local museum, where paleontologist Petr Kraft came across the trilobite as a child and noticed something crammed inside it. Kraft, now a researcher at Charles University in Prague and lead author of the new study, spent decades wondering what was inside the trilobite. Until recently, however, he lacked a way to peer inside the fossil without destroying the specimen.

To determine a noninvasive approach, Kraft teamed up with Per Ahlberg, a paleontologist at Uppsala University in Sweden. They landed on synchrotron microtomography, an imaging technique that creates detailed three-dimensional scans of internal anatomy. This allowed the researchers to not only look through the trilobite’s shell but also differentiate the contents inside.

The 3-D scans revealed a bevy of shell fragments lodged in each of the trilobite’s two stomachs. The shells belonged to an assortment of tiny seafloor creatures, including small clams; bivalve crustaceans called ostracods; cone-shaped animals known as hyoliths; and stylophorans, oddly shaped precursors to starfish.

The varied spread of seafood in the trilobite’s guts led the scientists to conclude that B. incola was an opportunistic scavenger that trawled the seafloor for carcasses and anything slow enough for it to catch. “It seems to have been going along like a living version of one of those little automatic vacuum cleaners, [sucking up] small animals that could be swallowed whole or crushed up easily,” Ahlberg says.

The remains inside the trilobite’s stomachs largely aligned with what the scientists expected to find, but they were surprised by the ancient arthropod’s healthy appetite. “What is remarkable is just how stuffed full it is,” Ahlberg says. “It seems to have been really gorging itself, eating very rapidly.”

The team speculates that the trilobite may have been molting, which could explain the feeding frenzy. Like living crustaceans, trilobites shed their shell as they grew. According to Ahlberg, crabs will sometimes ingest water or large amounts of food to bulk up and crack their old shell. The team described a crack along the top of the trilobite’s shell that may indicate it was starting to molt when it was buried.

Also surprising: the shells in the trilobite’s guts showed little sign of the damage that usually occurs when calcium carbonate shells are soaked in stomach acid. This suggested that the trilobite likely had alkaline or neutral conditions in its gut, similar to the conditions found in the stomachs of living mud crabs and horseshoe crabs. Because these animals are only distantly related to trilobites, Ahlberg thinks that a neutral gut may be an ancestral condition across arthropods.

Though the trilobite’s stomach may not have been particularly acidic, it still appears to have had a noxious gut. The researchers found areas in the fossil where scavengers had burrowed into the trilobite in search of soft tissue. The scavengers steered clear of the trilobite’s gut, however, revealing that bubbling enzymatic activity may have continued even after the animal died.

Losso says the new findings add crucial ecological context to trilobites, which survived for a period of 270 million years and whose fossilized shells have been studied by researchers for centuries. “We’ve wanted this kind of fossil for hundreds of years, and they finally got it,” Losso says. “It just proves that you have to keep looking for more fossils.”