Editor’s Note (9/2/21): This story is being republished following a 5-4 Supreme Court ruling that declined to block a Texas law banning abortions performed after six weeks of pregnancy.

When Texas Governor Greg Abbott signed a new abortion restriction into law on May 19, 2021, it marked a chilling milestone—a staggering 1,300 restrictions enacted by states since the U.S. Supreme Court protected abortion rights in 1973 in its Roe v. Wade decision. Unless rejected in court, it could block most abortion care in the state. Among many other harms, this would force Texans to travel an average 20 times farther to reach the nearest abortion provider. I have read and logged all of these 1,300 restraints—many as they were being enacted—in my 22 years at the Guttmacher Institute tracking state legislation on abortion and other issues related to sexual and reproductive health and rights. It’s an astounding number, and although many of these laws were blocked in court, most of them are in effect today.

But the news from Texas wasn’t the only bad news for abortion rights that week. Just two days earlier, on May 17, the Supreme Court announced that it would hear oral arguments on a Mississippi law—currently blocked from going into effect—that would ban abortion after 15 weeks of pregnancy. The news alarmed legal experts and supporters of abortion rights alike, with good reason.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

A central tenet of Roe and subsequent Supreme Court decisions has been that states cannot ban abortion before viability, generally pegged at about 24 to 26 weeks of pregnancy. By taking a case that so clearly violates almost 50 years of precedent, the court signaled its willingness to upend long-established constitutional protections for access to abortion. As the legal experts at the Center for Reproductive Rights put it, “The court cannot uphold this law in Mississippi without overturning Roe’s core holding.” And in fact, Mississippi followed up in July with a brief asking the justices to explicitly overturn that historic decision.

The Supreme Court that former president Donald Trump shaped, possibly for decades to come, by appointing conservatives handpicked by abortion rights opponents, is thus poised to deliver a potentially severe blow. Conservative state policy makers clearly feel emboldened by the 6–3 majority of justices opposed to abortion rights and a federal judiciary transformed by Trump’s more than 200 appointments.

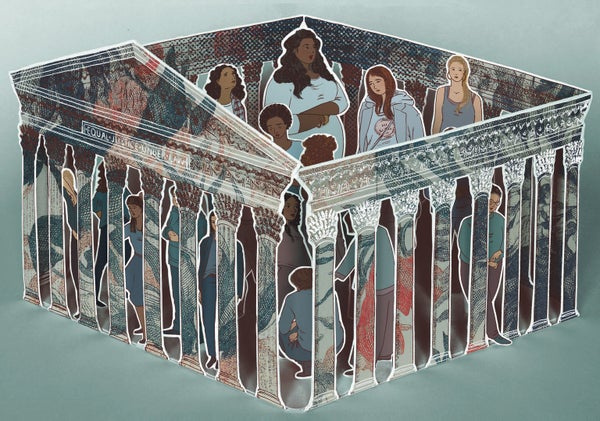

The decision to hear the Mississippi case comes as abortion rights and access are already under threat nationwide, with states on pace to enact a record number of abortion restrictions this year. As of August 5, 97 laws had been enacted across 19 states. That count includes 12 measures that would ban abortion at different points during pregnancy, often as early as six weeks—before most people even know they are pregnant. That is the highest number of restrictions and bans ever at this point in the year. For many people, affordable and accessible abortion care has already become an empty right on paper, even before the Supreme Court takes any new action. Currently 58 percent of women of reproductive age live in states that are hostile to abortion rights, facing multiple restrictions—from bans on insurance coverage to days-long waiting periods to intentionally onerous regulations that close down clinics—that build on one another to make abortion unobtainable for many.

A significant body of scientific literature shows that the adverse consequences of withholding abortion care are serious and long-lasting. Forcing someone who wants an abortion to continue a pregnancy requires them, against their wishes, to accept the great risks of pregnancy- and labor-related complications, which include preeclampsia, infections and death. And these risks fall much heavier on some communities than others. The U.S. has the highest maternal mortality rate among developed countries, with dramatic but preventable racial inequities caused by systemic racism and provider bias. Black and Indigenous women’s maternal mortality rates are two to three times higher than the rate for white women and four to five times higher among older age groups.

The risks of serious consequences do not end with a safe delivery. The Turnaway Study by researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, found that denying wanted abortion care can have adverse effects on women’s health, safety and economic well-being. For example, among women who had been violently attacked by an intimate partner, being forced to carry an unwanted pregnancy to term tended to delay separation from that partner, leading to ongoing violence. In addition, compared with women who got the abortion they sought, those who did not obtain a wanted abortion had four times greater odds of subsequently living in poverty. They also had three times greater odds of being unemployed and were less likely to be able to have the financial resources for basic needs such as food and housing.

The impact of restrictive policies is even further magnified in regions of the country where hostile states are clustered together, such as the South, the Great Plains and the Midwest. For people in those regions, traveling to a state with better access may not be an option because of the long distances and logistical or financial hurdles involved.

These barriers to abortion care are the biggest obstacle for people who are already struggling to get by or who are marginalized from timely, affordable, high-quality health care—such as those with low incomes, people of color, young people, LGBTQ individuals and people in many rural communities. Any further rollback of abortion rights would once again affect these populations disproportionately.

If the Supreme Court uses the Mississippi case to further undermine women’s rights to health care, things will get ugly—and fast. Twelve states have so-called trigger bans on the books (or nearly so)—meaning they would automatically ban abortion should Roe fall. Also, 15 states (including 10 of the states with trigger bans) have enacted early gestational age bans in the past decade. None of these early abortion bans are in effect, but with Roe overturned, many or all of them could quickly be enforced. Even if abortion rights are weakened by the Supreme Court rather than overturned, these same states will look to adopt restrictions that build on the decision.

But there are lots of ways to fight back. States supportive of abortion, primarily in the West and the Northeast, must step up to protect and expand abortion rights and access—both for the sake of their own residents and for others who might need to travel across state lines to seek services. Congress and the Biden administration must do their part by supporting legislation such as the Women’s Health Protection Act that would essentially repeal many state-level restrictions and gestational bans. Another bill that needs support is the EACH Act; it would repeal the harmful Hyde Amendment, which bars the use of federal funds to pay for abortion except in a few rare circumstances, and allow abortion coverage under Medicaid. There are also tireless advocates and volunteers, including managers of abortion funds in many states, who already assist abortion patients in paying for and accessing care. No doubt these vital efforts will increase dramatically if more states move to ban all or most abortions.

As federal protections for abortion are being challenged, people may go other routes to get an abortion. Abortion-inducing medication, whether under the management of a clinician in person or via telehealth or self-managed, is a safe and effective method, and many have been able to get such pills through the mail during the COVID pandemic. But here, too, barriers loom large. More state legislatures are looking to join the 19 that already ban abortion via telehealth. And just this year states started to enact bans on sending abortion-inducing pills through the mail.

Abortion is health care, plain and simple. There were more than 860,000 abortions in the U.S. in 2017, and at current rates almost one in four women will have an abortion by age 45. Supporters of abortion rights have to hope for the best and prepare for the worst. Most of all, we must stay in this fight until every person who needs an abortion is able to get safe, affordable and timely care.