From fish moving poleward in the oceans to mountain-dwelling birds and frogs inching upslope, animals all over the world are being forced by rising temperatures to leave their historic habitats in search of the conditions they’ve long been adapted to. Adding to this list, new research warns that climate change is now pushing venomous snakes out of their usual ecosystems—and into new, unprepared areas where they will pose a bigger public health threat.

For a recent study in the Lancet Planetary Health, researchers paired climate models with data on various venomous snake species’ current habitats to predict where and when they will likely start moving. If people don’t reduce greenhouse gas emissions, many snake species will lose their habitats and shift into places where they are currently not found by 2070, the study concluded.

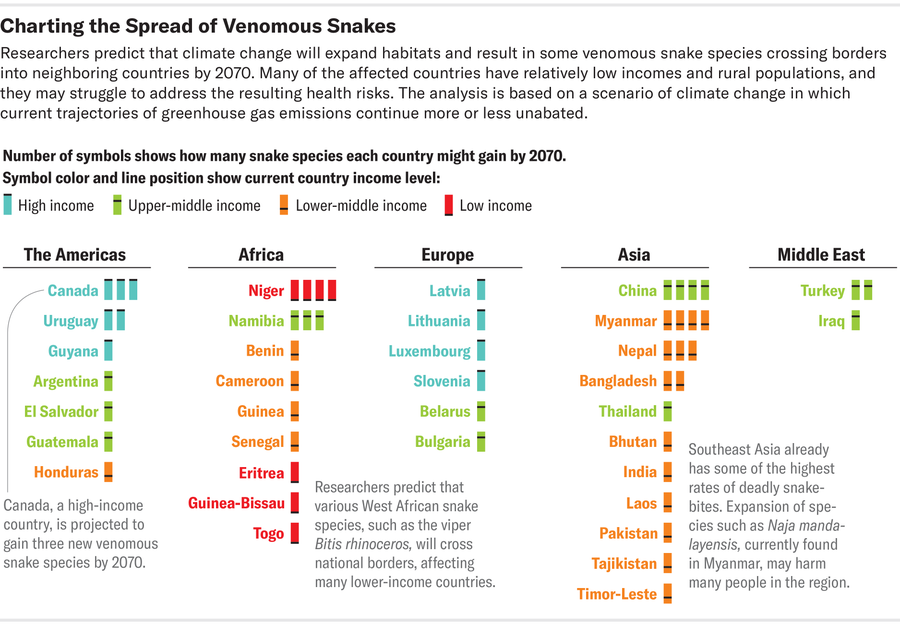

Most of this movement will occur around sub-Saharan Africa and certain parts of Asia—regions that already have the world’s highest snakebite incidence and mortality rates. The countries that will see the biggest increase of species from neighboring countries are China, Myanmar and Niger (with an estimated four news species each) and Nepal and Namibia (with three each). “Some places are going to have better climatic conditions for snakes,” says study co-author Pablo Ariel Martinez, an ecologist at Federal University of Sergipe in Brazil. He and his team found that savannas, grasslands and deserts will gain venomous snake species, while tropical rain forests will lose some.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Three viper species—Bitis rhinoceros, Vipera aspis and Vipera ammodytes—are expected to cover the most new habitat. These snakes typically inhabit dry, rocky areas with limited vegetation and show a preference for agricultural land over forests. As farming expands and temperatures become warmer and drier, these species are likely to find more suitable habitat near rural communities.

Rural communities in countries such as Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan, where snakebite is already a significant problem, are at risk as new snake species move in.

Amanda Montañez; Source: “Climate Change–Related Distributional Range Shifts of Venomous Snakes: A Predictive Modelling Study of Effects on Public Health and Biodiversity,” by Pablo Ariel Martinez et al., in Lancet Planetary Health, Vol. 8, No. 3; March 2024 (snake species data); World Bank Country and Lending Groups (income classification data)

Abul Faiz, an expert in tropical medicine, who formerly co-chaired the World Health Organization’s working group on snakebite, explains that rural areas of Bangladesh, where he is from, are more vulnerable because of the way people make a living. “People are at risk when working in the fields, around their homes and at night while sleeping on the floor of poorly built houses,” he says. Each year around 400,000 people in the country are bitten by venomous snakes, and 95 percent of these incidents occur in rural communities. Poor medical infrastructure, transportation problems and a shortage of qualified clinicians exacerbate the problem. “Medical doctors in rural hospitals are scared to use antivenom [because of a lack of instruction] and are not well trained [on it],” adds Faiz, who was not involved in the new study. Similar situations exist in Pakistan, India and Brazil alongside a reliance on traditional healers and unproven herbal remedies.

Most snake venoms consist of a mixture of toxic substances that can liquefy bodily tissues and destroy organs, paralyze breathing and other crucial systems or prompt internal bleeding. The mix of venom types varies both within and between species, meaning medical professionals need the specific antivenom for a given species. But making antivenoms is arduous and challenging; it usually involves injecting a small amount of venom into animals such as horses or sheep and then extracting the antibodies they produce in response—and production depends on the supply of venom, which has to be extracted by hand from deadly and sometimes rare snakes.

The highly variable timing of symptom onset complicates things as well. After a pit viper bite, for example, it may take anywhere from 30 minutes to an hour before redness and swelling even appear at the bite site. But a black mamba bite can kill in as little as 20 minutes. Caregivers need to know how much time they have in each snakebite case.

Some of the communities that are most vulnerable to new snake species may also be the least prepared. “Snake species have no political barrier, but the availability of antivenoms depends on the country,” Martinez says. Most countries stock antivenoms tailored to the species commonly encountered within them and will likely lack effective antidotes against the venom mixes of newly introduced snakes.

Extreme weather events such as floods can also worsen the problem. Previous research in Southeast Asia has shown that snakebite incidents increase during the monsoon season; this is because snakes and people both seek shelter away from floodwaters and become more likely to encounter each other. As climate change increases flooding, the risk of snakebite may rise even further.

Despite these threats to humans, the researchers emphasize that venomous snakes are crucial parts of ecosystems as predators of animals such as rats and insects. And some compounds found only in venom have potential medical uses unrelated to snakebite, such as cytotoxins with anticancer potential or proteins that can be used in antihypertensive drugs. If such snakes entirely disappear, “we end up losing a group of organisms that are valuable from a human perspective, economically and pharmacologically,” says Talita Amado, a former postdoctoral researcher at the German Center for Integrative Biodiversity Research and co-author of the new study.

But few communities would see any upside to an influx of deadly snakes, Faiz notes, which is why educating communities and providing more resources is an important step toward mitigating fears and preparing people. “It’s not just about having antivenom,” he says, but also about training health workers, using community-led prevention campaigns and improving medical facilities. Amado adds that maintaining updated databases of antivenoms and prevention strategies will be crucial in helping communities act quickly when snakes strike. “Poisoning is going to happen,” she says. “What will prevent people from being more or less negatively impacted will be local prevention.”