Posted on January 16, 2024 by Peter Lehner

What we grow and produce in America affects our air, water, climate, wildlife, public health, and more. The Farm Bill is likely the most significant environmental law Congress will address this year. This is the first of four blogs explaining how American agriculture can be more resilient and climate friendly. (More detail can be found in my book, Farming for Our Future; The Science, Law, and Policy of Climate-Neutral Agriculture, and related Columbia, Harvard, NYU, and Yale Law School blogs).

Our food system produces billions of pounds of food and fiber every year at a very low out-of-pocket cost to the consumer. Most Americans enjoy a wide variety of foods at their markets in all seasons (though much of the fruits and vegetables are imported). The American food system’s efficiency in churning out seemingly inexpensive calories is often a model to the world.

But when we consider the dramatic adverse impacts on the environment, our health, and food and farm workers, many studies have found the true cost of food is triple the price we see at the grocery store. While our industrial food system is producing food that appears inexpensive and abundant (indeed, food is comparatively so inexpensive to most Americans, that the country wastes over 35% of it), it’s also one of the largest sources of water, air, and climate pollution in the country. Most consumers — and, sadly, most lawmakers — don’t consider these environmental impacts or the poor treatment of workers and animals when discussing U.S. agriculture policy.

Today, most cropland is a vast monoculture of just one or two industrial-scale, chemical-intensive commodity crops, while about 99% of farmed animals are raised in “concentrated animal feeding operations” (CAFOs) that crowd tens of thousands or even millions of animals into restrictive stalls or pens. only 6% of farming operations produce 90% of all of meat, dairy, and poultry.

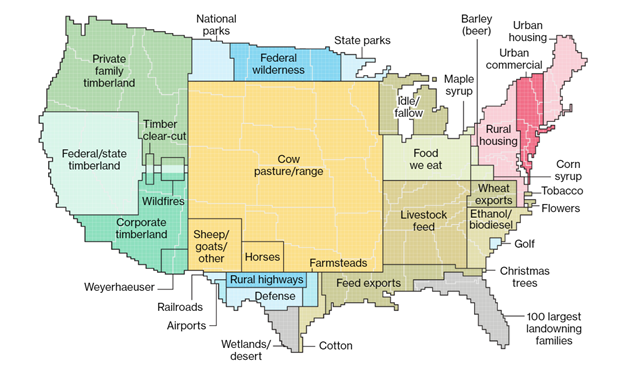

Industrial agriculture’s massive footprint occupies over 60% of the contiguous U.S. This land used to be vast wetlands, native grass-covered prairie, or forest — natural systems adept at storing carbon, producing abundant wildlife, and filtering polluted water but over time has been converted for agricultural use. For example, between 2007 and 2012, 7.8 million acres of natural habitat were converted to cropland due largely to ethanol mandates and increased global demand for livestock feed. Today, very little agricultural land provides these important environmental benefits.

This land use is not nutritionally efficient: while over two thirds of all agriculture land is devoted to livestock, Americans only get about 30% of their calories from meat, dairy, and eggs. Less than a quarter of cropland is devoted to food directly eaten by humans, with the rest going to mostly to animal feed and biofuel feedstock, and it takes many pounds of grains to produce a pound of beef.

Not only is it land inefficient, but industrial agriculture is also closely tied to the petrochemical industry because of its dependence on fossil fuel-based fertilizers and pesticides, chemicals that are themselves highly detrimental to public health and the environment. Excess pesticide and fertilizer use causes massive disruptions to natural ecosystems, including the massive “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico and the destruction of pollinator habitats critical to our food supply. At the same time, these toxic chemicals are harming rural communities which must contend with the expensive removal of nitrate pollution from drinking water, while increasing their risk of numerous human health harms, including blue baby syndrome. New research also links nitrate consumption to adult and pediatric cancers.

Of all the true impacts of industrial agriculture, perhaps the one that is least understood and yet most critical to address is on our climate. This impact is so great that the country and the world simply cannot meet our collective climate goals without significant changes to how we grow food. And while other sectors are reducing their emissions, agriculture’s emissions are rising, thereby increasing its proportional share of climate emissions.

The two primary greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture are methane and nitrous oxide. Bovine guts generate methane, which is 85 times more powerful than carbon dioxide over 20 years. The millions of cows in the U.S. emit more methane than the fossil fuel gas system. Nitrous oxide is even more damaging to our atmosphere. It’s released in large volumes by animal manure and by farmers’ routine application of more nitrogen fertilizer than crops require. Then, when wild and fallow land is plowed to feed this inefficient system, the land releases tremendous amounts of stored carbon. And land already converted to agriculture is a missed opportunity for carbon sequestration. Thus, collectively, our industrialized agriculture and food sector drives approximately one-third of our country’s contribution to climate change — about the same as the transportation system’s total climate emissions.

The good news is that this sector is ripe for change.