California has made significant strides towards reducing pollution from vehicles by adopting trailblazing policies to accelerate the adoption of both passenger and heavy-duty zero-emissions vehicles. The state is continuing this momentum by developing an ambitious regulation to require the state’s largest medium- and heavy-duty (MHD) commercial fleets to begin transitioning to electric trucks in 2024, eventually requiring 100 percent of MHD vehicles purchased by large commercial and public fleets that operate in the state to be zero-emissions in 2042. This new regulation would apply to delivery vans, big rigs, box trucks, and buses.

The Advanced Clean Fleets (ACF) rule has the potential to significantly reduce climate-warming greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as well as harmful air pollutants like fine particulates (PM2.5) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) from the numerous commercial and government fleets of MHD vehicles in the state. California’s Advanced Clean Trucks (ACT) rule passed in 2020, which required manufacturers to sell an increasing percentage of zero-emissions MHD vehicles, was an excellent start. Now, the proposed ACF goes a step further, and would require fleets to purchase zero-emission vehicles. The California Air Resources Board (CARB) estimates this will increase the number of clean trucks and buses on California’s roads and highways by 60 percent in 2035 and nearly 70 percent in 2050 compared to the ACT.

Medium- and heavy-duty vehicles (like delivery vans, tractor trucks, box trucks, and charter buses) are responsible for an outsized amount of pollution – although just 7 percent of vehicles in the state, they emit more than one-quarter of GHG emissions, more than 60 percent of smog-forming NOx pollution, and more than 55 percent of lung- and heart-harming PM2.5 pollution from California vehicles.

The ACF includes four primary pillars, focusing on state and local public agency fleets, large commercial and federal fleets, drayage operations, and a continuation of the ACT rule requiring 100 percent zero-emissions truck sales by 2040. In a previous blog, I went into more detail on the components of the rule as proposed by CARB.

In this entry, I propose two key changes CARB could make to supercharge the effectiveness of the ACF and create beneficial, short-term results for freight-adjacent communities, places that have been historically and disproportionately impacted by air pollution.

Regulate more tractor trucks, including the smaller fleets

Among the millions of vehicles on California roads and highways, tractor trucks (big rigs, 18-wheelers, semis, lorries, or whatever you want to call them) constitute a mere 1 percent. However, this relatively small group of large vehicles on our roads is responsible for a disparate 13 percent of GHGs, 25 percent of PM2.5, and 33 percent of NOx emissions from all on-road transportation in the state. These trucks regularly operate along industrial corridors – areas that often flank communities disproportionately impacted by air pollution.

The ACF is an opportunity to deliver meaningful reductions in air pollution for the most affected communities, but the current proposal falls short of what is technologically and economically feasible.

In its current form, the rule would require fleets with 50 or more covered MHD vehicles or $50 million in annual revenue to comply. However, the composition of a commercial fleet is more important than its size in many cases, given that a fleet of 10 tractor trucks could emit more pollution than a fleet of 50 delivery vans depending on daily mileage, fuel type, and other factors. So, while a numeric threshold of 50 may look good on paper (everyone like an easily divisible number), the rationale around setting this critical piece of the regulation should be data-driven and focused on desired results.

This compliance threshold is one of the most pivotal parts of the regulation and it should be based on well-researched and tested desired outcomes – e.g. if we want X amount of emission reductions, we should regulate fleets of Y size and greater.

In keeping with this, I decided to run the numbers myself using a massive dataset that represented all tractor trucks operating in California (it nearly broke my computer!).

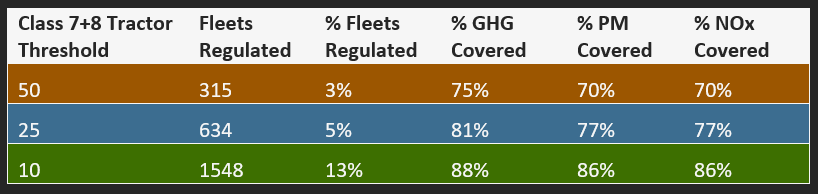

The results were equally interesting and enlightening. I found that a numeric compliance threshold of 10 is the sweet spot for capturing nearly all tractor emissions under the rule while avoiding a significant increase in the number of regulated small businesses and agency workload.

At a numeric threshold of 50, only 3 percent of California tractor truck fleets would be covered under the ACF. However, lowering the threshold to 10 could deliver around 15 percent greater GHG, PM2.5, and NOx emissions reductions from tractor trucks while still only regulating around 13 percent of California tractor fleets. Because of their outsized contributions to air pollution in the state, a 15 percent increase in emissions reductions is significant and worth pursuing.

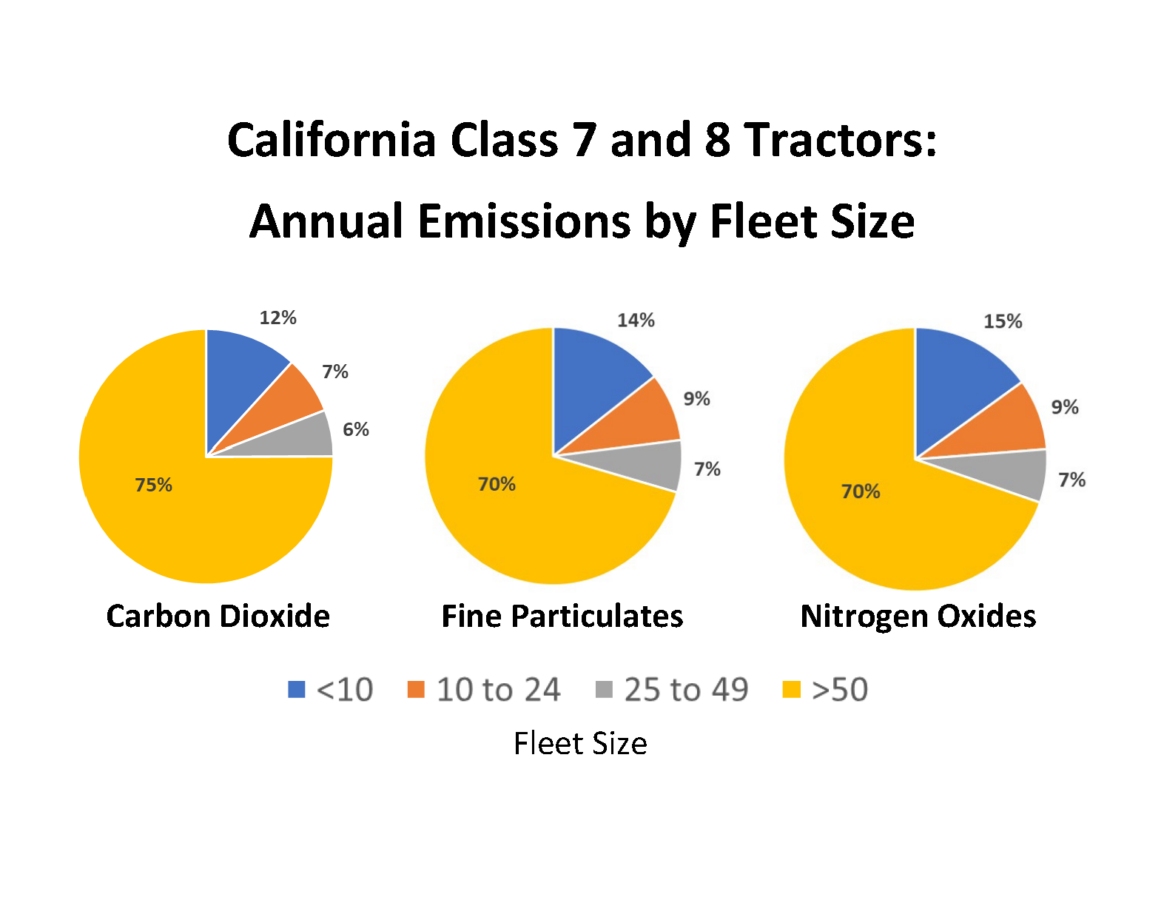

In California, nearly 90 percent of tractor trucks on the road belong to about 15 percent of commercial fleets. These fleets, those with more than 10 tractor trucks, are responsible for the lion’s share of emissions: about 85 percent of fine particulate and ozone-forming nitrogen oxide emissions and just under 90 percent of greenhouse gas emissions from all California tractors (see the pie charts below).

A lower threshold would bring more reductions in air pollution sooner for the communities who need it most. While this, along with climate change mitigation, should be the primary focus of the rule, the ACF should also be tailored to avoid impacts on small businesses. A compliance threshold of 10 for tractors is a good balance because it captures the majority of emissions but avoids regulating the smallest, and most economically vulnerable, tractor fleets.

This has two positives. First, regulations should be tailored equitably to avoid impacting vulnerable business owners whenever possible. Other programs are available to assist the mom-and-pop fleets in electrification. Second is a lesson I learned while working in state government: typically, the smallest emitters require the most attention from agency staff because these small businesses often do not have the capacity to employ staff internally with expertise in regulatory compliance. This means that agencies can spend the most time on the least consequential emitters (especially in emissions reporting programs).

Move up the target date by four years

The current draft of the rule includes a requirement for 100 percent zero-emissions truck sales by 2040, but our research shows that health, environmental, and economic benefits could be significantly increased by moving the date up four years to 2036. Not only do the climate and air quality crises demand that we electrify as fast as possible, but a sooner date also sets a clear market signal that California is serious about environmental justice and addressing climate change. This will influence accelerated development and buildout of charging infrastructure for MHD vehicles as well as reductions in production costs for vehicles through economies of scale. Moreover, CARB’s own research shows that this is both economically and technologically feasible.

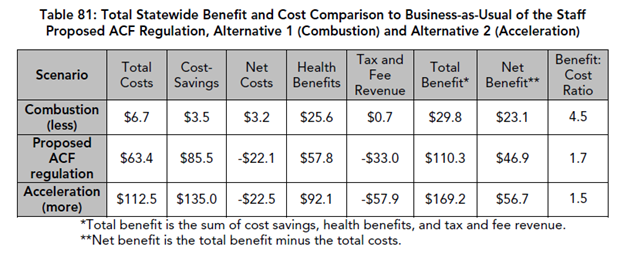

Moving the requirement for 100 percent zero-emissions HDV sales up to 2036 from 2040 would result in more than 130,000 additional electric trucks on the road in 2050, according to research recently contracted by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) and the Natural Resources Defense Council. These additional clean trucks are estimated to affect an increase in net societal benefits of nearly $10 billion compared to the current ACF proposal.

Replacing dirty trucks with zero-tailpipe emissions vehicles is key to improving air quality and our study estimated that moving up the 100 percent sales date by just four years would increase the number of avoided premature deaths, avoided hospital visits, and other related illnesses by about 10 percent through 2050. This represents nearly $3 billion in additional cumulative health benefits.

Increased environmental benefits from more stringent regulations can often come with additional costs for regulated industries. However, the ACF and vehicle electrification are a win-win for the environment, human health, and industry. In addition to significant increases in monetized health benefits, a sooner 100 percent zero-emissions sales date would bring additional cost savings to California truck fleets, mostly through increased fuel and maintenance savings. Compared to the proposal, the 100 percent by 2036 option is estimated to increase cumulative fleet savings by $300 million, roughly 14 percent. By all significant measures we’ve analyzed, the dollars make sense for an accelerated 100 percent zero-emissions timeline.

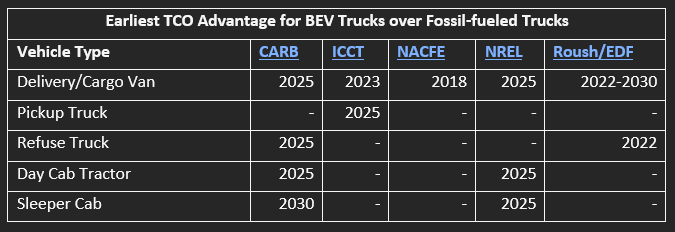

Industry groups, environmental advocates, internationally-lauded research organizations, and CARB have all independently published research showing that electric trucks will reach cost parity with their combustion counterparts around 2030, driven largely by the rapidly declining cost of batteries. A 100-percent zero-emissions sales date of 2036 lags between 10 and 22 years behind these studies’ estimates for cost parity between MHD EVs and combustion models, depending on the vehicle.

If a non-emitting option is both available and more cost-effective to own and operate over its lifetime, why then would we allow its polluting equivalent to be sold? I would argue that the date of the 100 percent zero-emissions sales requirement should be largely influenced by this question.

What’s holding the regulators back?

So why hasn’t CARB considered these improvements if they provide the benefits I’ve outlined? In short, they have. Both a reduced threshold and a faster timeline for zero-emissions truck sales and fleet electrification were considered under an “Accelerated Alternative” in CARB’s Initial Statement of Reasons (ISOR), which examines the costs and benefits of different regulatory options. While staff have worked hard and in good faith on this rule, our deep dive into the data and related analyses show we can go further than the proposed rule.

The ISOR mentioned several reasons why these options couldn’t be pursued, including feasibility for fleets while the market is still developing, the increase in regulated fleets, impacts to small businesses that may have access to less capital, and issues related to the cost and timeline of charging infrastructure buildout in the early years of the program. Each of these concerns, although legitimate, is anticipated to be addressed as the market continues to expand rapidly, with the help of provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act that support zero-emission vehicles, ongoing funding from state agency programs and, also, by tailoring the ACF to avoid impacting the smallest businesses.

With well over 100 models of zero-emissions MHD vehicles available today, the market for clean trucks and buses is expanding and expected to accelerate. CARB’s analysis of battery costs in the ACF ISOR shows rapidly declining costs for MHD vehicle batteries, with smaller trucks lagging behind passenger cars by just two years and larger trucks by five years (See Figure 10 in the above link). By this measure, battery costs for the largest trucks, like sleeper cab tractor trucks, will be under $100/kWh around the time the proposed language would bring sleeper cabs into the program in 2030. A lower compliance threshold for these larger trucks could expedite the decline of battery costs by pushing R&D and innovations as well as through economies of scale as production ramps up to meet demand. While it is true that EV battery prices have increased this year compared to last year despite increased production, battery prices are anticipated to fall to $100/kWh by 2024.

CARB staff makes a good and vital point that smaller businesses often do not have access to capital as readily as large businesses, however, a lower compliance threshold only for tractors would avoid regulating smaller fleets with fewer resources. These businesses would not have to begin compliance under the regulation until 2027 or 2030, depending on the type of tractor, which allows half a decade to plan. Furthermore, the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act establishes a tax credit of up to $40,000 for the purchase of larger zero-emissions commercial trucks through 2032. CARB staff estimates the cost of a new battery-electric Class 8 Day Cab tractor to be $176,000 in 2030, while the same model with a diesel motor to be around $150,000. With the federal tax credit, fleets could purchase the electric version of this truck for the same price as the diesel and begin saving significantly on fuel and maintenance on day one.

While there are very few publicly available fast charging stations for heavy-duty trucks today and CARB staff are correct to raise this issue, most MHD ZEVs return to their home bases each night—especially delivery vans and day cab tractor trucks—and are anticipated to charge at these depots. Businesses can start planning for the development of charging on their own properties while the public-facing infrastructure develops. Already, technology for MHD charging is advancing and a fast-charging standard to rapidly charge big rig-sized batteries, known as the Megawatt Charging System, is expected to be finalized in 2024.

Public charging is likely to be used more by long-haul tractors, which would not be regulated under the rule until 2030 under the current proposal. The buildout of public MHD charging will certainly be a momentous task and require some grid upgrades, but it can and will be done. Both government and the private sector are planning for MHD charging infrastructure. Vehicle manufacturers are also getting into the infrastructure game. Volvo, for example, plans to have a California corridor of high-powered chargers online by the end of 2023. Daimler, along with NextEra Energy Resources and BlackRock Renewable Power, plans to begin construction of a nationwide charging system for long-haul tractor trucks in 2023.

California’s Energy Commission committed over $300 million in investments toward MHD charging infrastructure for the 2022-23 fiscal year and even more funding is slated for the coming years. This funding supports several programs, including EnergIIZE, which offers a number of funding opportunities for the development of MHD charging infrastructure. EnergIIZE includes a funding category for MHD public charging, offering up to $500,000 in incentives per project. Another funding category in the program offers up to three-quarters of a million dollars for the planning and development of depot charging infrastructure projects.

In addition to state support, the federal government is supporting electric vehicle charging infrastructure deployment through the Inflation Reduction Act and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and utilities are beginning to step up to the role they can play in support of expanding MHD charging. A group of large West Coast utilities came together in 2020 to collaborate and study the issue and found that just 27 sites across the Interstate 5 Corridor could serve anticipated demand in 2030, the first compliance year for long-haul tractors under the proposed ACF.

The proposed ACF rule is very good, and could be better

While the draft ACF CARB staff have proposed will create significant reductions in climate-warming GHG and air quality emissions, if the rule focused more on tractor trucks and accelerating the requirement for 100 percent zero-emissions sales, then it would deliver faster and more meaningful benefits without significantly increasing regulatory burdens on affected businesses or greatly expanding administrative work for CARB staff.

As it stands the ACF is certainly an ambitious regulation, yet it’s possible to strengthen the proposal given current technology, positive economics, and developing infrastructure. Most of all, it’s necessary given the climate crisis and inequitable access to clean and healthy air.

UCS is working closely with our allied partner organizations to push for the most ambitious and protective rule feasible. Adopting a strong ACF will help to accelerate the market and technologies for zero-emissions MHD vehicles not just in California, but across the nation. The sooner we reach cost parity, the sooner we can significantly reduce emissions from freight and goods movement.