- Science News

- Young Minds

- Alfred Wallace – Overshadowed Pioneer

Alfred Wallace – Overshadowed Pioneer

Image: Evstafieff/Down House, Downe, Kent, UK/English Heritage Photo Library/Bridgeman

Frontiers for Young Minds takes you on the journey of the tumultuous life of a radical scientist who contributed more to the development of the currently known evolutionary theory than you might be aware of. Read the story of Alfred Russel Wallace.

You may link the famous Charles Darwin with discoveries in evolution by natural selection, but have you heard of his often-overlooked contemporary Alfred Russel Wallace? Known in the 19th century for his huge developments in evolutionary theory, Wallace has since been overshadowed by Darwin’s social and scientific status.

Wallace’s life work was highly impactful and, if you haven’t heard of him yet, be sure to read on and discover more! This 19th century maverick was unafraid to champion unconventional or unpopular ideas, voiced stark criticism of social inequality, and led a lifetime of scientific and spiritual exploration.

A Young Englishman Inspired by Naturalists

From a young age, Wallace explored various career ideas like surveying, law, and mechanics. It was when the keen reader met naturalist and explorer Henry Bates that his interest in collecting insects and discussing popular works of naturalist theory began.

Inspired by the accounts of explorers like Robert Chambers and Charles Darwin, Wallace was keen to travel the globe on his own adventures. In 1848, Bates and Wallace headed for Brazil where they hoped to expand their personal collections and to gather evidence of transmutation [the conversion or transformation of one species into another]. During their travels, the pair observes people, languages, geography, plant- and wildlife of Belém [the gateway to the Amazon river] and Rio Negro [an Amazon tributary river].

Wallace’s hopes to find proof of evolutionary theory set him apart from a rather skeptical generation, transmutation had been widely discussed but was not generally accepted. As a radical, Wallace admired controversial science, writing that hypothesized evolutionary origins of the earth, solar system, and living things were ‘rather ingenious’ and ‘strongly supported by some striking facts and analogies.’

Wallace believed that these theories could serve as encouragement for the collection of facts by students of nature, providing an ‘object to which [evidence] could be applied when collected.’

The Undampened Spirit of a Revolutionary

Disaster struck in 1852 when the voyager set sail for his return to the UK. Following four years of exploration and collection, Wallace’s ship tragically caught fire and all but a few of its contents were lost. Saved by a passing ship, the ships crew returned to the UK empty-handed; Wallace’s artefacts, notes, and sketches were destroyed.

Left only with the objects he’d shipped from Rio Negro, Wallace’s work was far from over; he went on to write six academic papers and two books, increasingly making connections with other British naturalists.

At age 31, Wallace set sail once again, this time to the Malay Archipelago (now Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia.) He sought to continue his exploration of natural history, while collecting artefacts to sell. Wallace’s efforts amassed more than 125,000 specimens in the Malay Archipelago alone, thousands of which were totally new to science. Collections and related notes, including 80 bird skeletons from Wallace’s travels, can still be found in international museums today.

Image from https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/who-was-alfred-russel-wallace.html

First Contributions to Natural Selection Theory

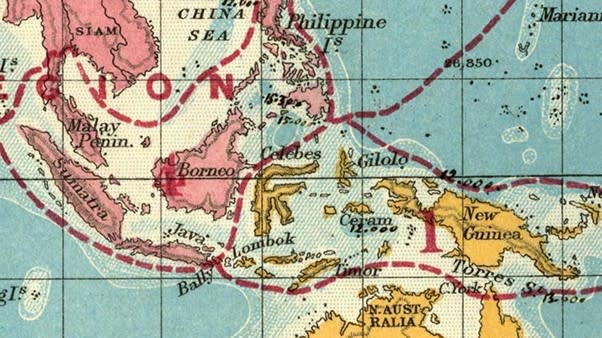

During his fieldwork, Wallace observed differences in wildlife on either side of a conceptualized divide of the Indonesian archipelago. This boundary was later named the ‘Wallace Line’ by Thomas Henry Huxley and represented a difference between animals on the eastern and western sides with respective Australian and Asian origins.

Wallace’s understanding of varied zoological regions highlighted the preservation of certain primitive varieties of a species within isolated territories, such as the remaining lemurs of Madagascar. Such biogeographical discoveries contributed to Wallace’s refined thoughts on evolution and his independent insights on natural selection principles.

In 1858, Wallace sent his paper for review by Charles Darwin, who had previously commented that they thought alike. Although the paper did not use the term ‘natural selection,’ it had outlined potential mechanisms of the evolutionary deviation of various species as a result of environmental pressures.

Wallace noted that animals breed in much larger quantities than humans, though the populations somehow remained constant. He concluded that only some offspring survive and questioned the reasons for this. His observations of vast individual variation suggested that only individuals with beneficial modifications would survive and reproduce, versus the less effective variations of the same species.

Image from https://oumnh.ox.ac.uk/alfred-russel-wallace

A Good Friend to Have

Darwin praised Wallace’s ideas and insisted on the paper’s publication, declaring that ‘Wallace’s terms now stand as heads of my chapters.’ Still stationed in South America at the time, the explorer was not aware of the rapid publication of his and Darwin’s work, though he later graciously accepted Darwin’s endorsement and co-authorship. Wallace continued to fiercely support his senior, publishing rebuttals to criticisms of Darwin’s works.

Although the researchers disagreed on points like sexual selection, predator warnings, and spiritualism, Wallace was the most-cited naturalist in Darwin’s work Descent of Man and the two often exchanged and encouraged each other’s ideas. Darwin sympathized with Wallace’s financial instability and even pushed for a government pension in recognition of his contributions to science.

A Lifetime Cause for Thinking Big

Wallace admired the beauty of nature and treasured memories of an inviolate Amazon rainforest. His writing highlighted the dangers of ignoring sanctity in nature and he criticized ongoing coffee cultivation. Ahead of his time in many ways, Wallace cautioned that deforestation and other human activity would adversely impact the complex interactions between vegetation and climate. In his 1904 book Man’s Place in the Universe, Wallace also represented the first serious attempt by a biologist to evaluate the possibility of life on other planets.

Besides his scientific interests, Wallace opposed the status quo of rich private landowners and lobbied for state-owned land to be used in the way most beneficial to the majority. The revolutionary was also an advocate for women’s suffrage; condemned militarism; denounced unjust systems preventing criminal rehabilitation; and criticized European colonialism.

In his 90 years, Alfred Russel Wallace was a force to be reckoned with. Corresponding with a lifetime of modesty, Wallace requested that he be buried in a small cemetery at Broadstone, Dorset, despite suggestions of a Westminster Abbey funeral by his peers. The scholar's daring works, available to explore in their entirety at Wallace Online, transformed and propelled evolutionary theory.

Inspired to learn more about evolution?

Take a look at our Biodiversity section and these Frontiers in Young Minds articles: Evolution in a Bottle and A Brief Account of Human Evolution for Young Minds.

Do you know the story of a forgotten scientist that should be heard? Email us with your idea at kids@frontiersin.org!