Editor’s Note (8/4/23): On August 4 NASA announced that it had successfully reestablished communications with Voyager 2.

Earth may not hear from one of its most beloved spacecraft until mid-October because of a glitch that altered Voyager 2’s orientation to our planet. But NASA engineers have caught a “heartbeat” signal that the agency says might help it reestablish communications sooner.

“A series of planned commands sent to NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft July 21 inadvertently caused the antenna to point 2 degrees away from Earth,” wrote NASA officials in a July 28 statement. “As a result, Voyager 2 is currently unable to receive commands or transmit data back to Earth.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Since the initial glitch, NASA has detected what mission personnel call a carrier signal from the spacecraft, which confirms that it’s still operating properly.

“A bit like hearing the spacecraft’s ‘heartbeat,’ it confirms the spacecraft is still broadcasting, which engineers expected,” wrote officials at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which operates the spacecraft, in a tweet on August 1. “Engineers will now try to send Voyager 2 a command to point itself back at Earth.”

If that doesn’t work, NASA expects Voyager 2 will resume communications in October thanks to regularly scheduled commands that direct the spacecraft to reset its orientation. The next of these reorientation maneuvers will occur on October 15.

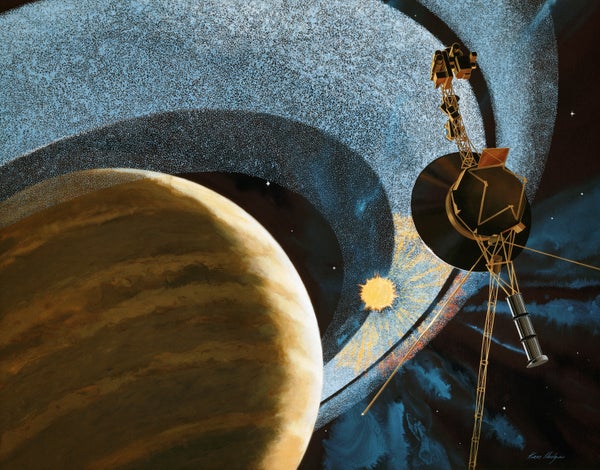

Voyager 2 launched in August of 1977, about two weeks before its twin Voyager 1, which swung past Jupiter and Saturn, followed by Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. Voyager 2 took a different path, zipping by Jupiter and Saturn and then Uranus and Neptune. To date, it remains the only spacecraft to ever visit the latter two planets.

The Voyager missions have also played a unique role in American culture. Each spacecraft carries a golden record: a phonograph that includes greetings from languages around the world and a host of musical excerpts. Each record is encased in a sleeve that maps Earth’s location with respect to 14 pulsars, which are rotating neutron stars that pulse radiation at very precise intervals. And the Voyager 1 mission captured the iconic photograph known as the “Pale Blue Dot,” which depicts Earth as a tiny speck against the vastness of space.

Both probes have continued trekking across that vastness. Voyager 2 is now nearly 12.4 billion miles from Earth, some 133 times our planet’s distance from the sun. Until the glitch, it took nearly 18.5 hours for a signal from Earth to reach the spacecraft and another 18.5 hours for humans to catch a response.

Five instruments remain operational on Voyager 2. In 2018 it moved into interstellar space, where the influence of the sun wanes. Now the spacecraft is working to help scientists understand what happens, for instance, where cosmic rays overpower the solar wind, the stream of charged particles that constantly flows off the sun.

Voyager 2’s power is waning, however, as it treks ever farther from the sun and its nuclear power source ages. NASA has already shut down certain components to save power, but soon officials expect to turn off additional instruments in hopes of extending the spacecraft’s operations through 2030—a particularly impressive feat, given that the mission was only designed to last four years.