Elizabeth Ann just became a triplet—at three years old.

This black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes)—the first endangered species in the U.S. to ever be successfully cloned—was joined late last year by her genetically identical baby sisters Antonia and Noreen, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) announced Wednesday. All three come from the same cryogenically preserved cell line, obtained from a ferret named Willa, who lived in Wyoming in the 1980s.

As climate change, habitat loss and dwindling food supplies bring ever more endangered species “crashing to the brink,” a successful cloning such as this is a serious game changer, says Ben Novak, head of de-extinction efforts at Revive & Restore, a nonprofit outfit that applies biotechnology to conservation.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Novak’s organization, along with ViaGen Pets & Equine and the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, is now teaming up with the FWS on a major project to cryogenically store tissue from every endangered species in the U.S., “just in case,” says Seth Willey, a FWS deputy assistant regional director who heads the project’s pilot phase. “It’s an insurance policy against future loss of biodiversity in the wild.”

It all began back in 1981 when scientists in Wyoming found and captured 18 black-footed ferrets—a species that had been thought to be extinct. A few of these animals bred in captivity, and their descendants were freed into the wild in an attempt to keep the species going. But scientists, worried about a future lack of genetic diversity in the fragile population, froze cells from Willa and one male, both of which had not bred naturally. The researchers wanted to bank this genetic material for potential later use to spice up the gene pool; they believed cloning would, in the future, become a practical reality.

Black-footed ferret clone Antonia.

Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (CC BY 4.0)

Now that it has, the FWS biobanking project aims to eventually collect tissue samples from at least one male and one female of every one of the hundreds of endangered animal species in the U.S. It will create a genetic library of sorts, akin to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. The Svalbard program has been collecting seeds from all over the world since 2008 to safeguard and bank them—in a secure facility on a Norwegian Arctic island—in case they are needed for future food supplies. Though more than 1,600 U.S. plants and animals are listed as endangered or threatened, fewer than 14 percent have been cryopreserved. The new project is expected to provide a more systemized biobanking pipeline.

Because so many of today’s endangered species are already severely lacking in genetic diversity, saving their genes through tissue collection now could prevent extinction later. Beyond the black-footed ferret, there are few, if any, species for which cloning can bring back valuable diversity today. The known populations of the red wolf, Wyoming toad and Columbia Basin pygmy rabbit descend from just a handful of individuals captured for conservation breeding, Novak says. “People saved them..., [but] there is no single cell line or even tissue sample in a freezer somewhere. They didn’t collect them. They didn’t put them away,” he says. “To my knowledge at the current time, there is no equivalent to Elizabeth Ann” to act as a source of fresh genetic material in any other endangered species. And though it is likely too late for biobanking to work for some of those already bottlenecked populations, the project has other species, such as the northern long-eared bat and Penasco least chipmunk in it sights

Field biologists used a Sherman trap (top left) to capture an endangered Preble’s meadow jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonius preblei) and take a small skin sample for the biobanking project before releasing it back into a site where its habitat has been restored.

Kika Tuff/Revive & Restore

Field biologists from all over the country began collecting samples about six months before the pilot project was publicly announced in October 2023. The samples are saved in a cryogenic kit provided by Revive & Restore. Tissue is carefully obtained, usually from an animal’s ear, using a tool that looks like a paper hole punch; Novak says this doesn’t harm the animal. “The biologists working with endangered species are highly trained, and we have a rigorous permitting system to ensure animals do not face undue capture or stress,” Willey says.

Scientists will use these samples to generate cell lines that will produce millions of cells. These can be cryogenically preserved to give future scientists hundreds of thousands of cells with which to work. “Future recovery efforts decades from now have additional genetic rescue opportunities that otherwise would not exist,” Willey says. The genetic information will also be sequenced for use today by scientists working on captive breeding, climate resilience and other aspects of conservation.

A Mexican gray wolf (Canis lupus baileyi) is examined before its tissue is collected for the biobanking project.

Rebecca Bose/Wolf Conservation Center

Tissues from 13 endangered species have been collected so far, including from the New Mexico meadow jumping mouse, Peñasco least chipmunk, Texas kangaroo rat, Mexican wolf, Sonoran pronghorn and Mount Graham red squirrel. The goal for the pilot phase is 25 species in all. The samples are being stored at –256 degrees Fahrenheit at a U.S. Department of Agriculture cryogenic facility in Fort Collins, Colo.

Not all types of animals can currently be cloned because of cloning technology’s reliance on surrogates and live births. “For birds, laying hard-shelled eggs makes techniques like cloning and [in vitro fertilization] virtually impossible,” Novak says. Reptiles have similar limitations. “But if we have the cells, maybe there are things that we will be able to do in the coming decades that astonish everyone,” he says.Revive & Restore is looking at one approach called germ-line transfer for potential use with bird eggs. In this process, stem cells called primordial germ cells are isolated from a developing bird embryo and cultured in a petri dish. Through a small window in an eggshell, the cells are then transferred into another embryo that is at an early embryonic stage; the cells are injected directly into its bloodstream, where they circulate to developing testes or ovaries and become sperm or eggs. When this embryo becomes an adult, it uses these donated cells to reproduce, making it a surrogate parent.

Those involved in the biobanking project hope to extend it beyond the pilot. It’s a relatively inexpensive undertaking, says Novak, who hopes the U.S. Department of the Interior will provide $1.5 million dollars in funding.

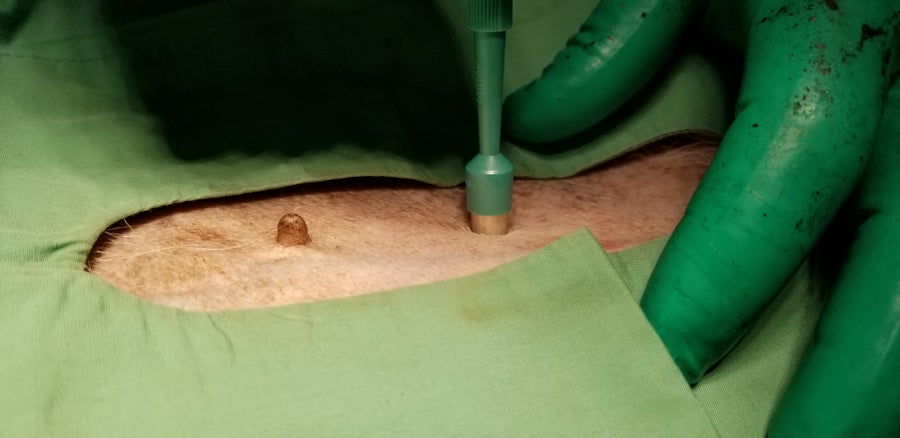

Skin tissue is collected from a critically endangered Mexican gray wolf (Canis lupus baileyi).

Rebecca Bose/Wolf Conservation Center

Samantha Wisely, a population geneticist who isn’t involved with the biobanking project but is a member of a black-footed ferret genomics working group co-founded by Revive & Restore and the FWS, says that the U.S. should also help developing countries start similar programs to ensure conservation equity. And she notes the need to protect remaining critical habitats as well. “This is not going to save species if they don’t have habitat to be able to go back to,” says Wisely, who directs the Cervidae Health Research Initiative, a state-funded liaison between the deer farm industry and the University of Florida. Otherwise “it’s just a zoo in a petri dish, and I don’t think that’s what conservation is.”

Willey also underscores that biobanking is not a panacea—but rather a single item in the recovery toolbox. “Some people think if you have [species] in a freezer, you don’t need them in the wild,” he says. “That’s just not true.... We can’t lose what we have in the wild. But if we do, it’s good to have an insurance policy.”

Wisely agrees that biobanking is “an essential part of the puzzle.” And “if we don’t do it now,” she says, “we can’t do it later.”

Editor’s Note (4/24/24): This article was edited after posting to correct the description of other species that the biobanking project has in its sights and to clarify some of the organizations involved in the effort.