COP16 Dispatch: Week 1 From Policy to Practice: the Role of Field Station Networks in Implementing Science-Based, Inclusive Conservation

By Claire Bandet, master’s student at the University of Pennsylvania

This panel convened to discuss the activities and outputs of several field stations in tropical Africa and South America as well as to discuss the potential benefits of establishing a co-working network between them. The following is a summary of the arguments made by the panelists.

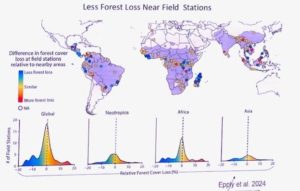

Biological field stations are a uniquely effective nexus between local, national, and global scale interests. Field stations tend to be established in areas with high conservation value because those areas tend to be the ones biologists are interested in studying. This creates a positive feedback loop: as the area becomes more studied, it becomes more valuable to science. As data is gathered, it can be used both to further scientific understanding and to ground arguments that the area should be protected. Looking at a map of deforestation around the world, one notes that forests around field stations are either preserved or are being improved much more than around any other place.

Field station networks as the future of conservation poster presented at COP16 on October 23, 2024.

Field stations by their nature, bring infrastructure and expertise into otherwise underserved areas. They increase scientific infrastructure by installing equipment like flux towers, molecular biology labs, acoustic monitoring tools, and building herbariums.

They also contribute hugely to local capacity building. The Centre ValBio Research Station in Madagascar has trained local people at all levels, yielding PhDs, professors at the University of Madagascar, and NGO workers. They hire local people to be field assistants and empower them to develop their own projects by providing resources and training such as bringing experts from the Missouri Botanical Garden to the station to help train people to build the herbarium. The station thus not only generates important science, but also provides valuable social and economic resources like healthcare, agricultural training, and youth investment. This kind of capacity building is common across the field stations represented.

All the panelists stressed the work that their stations did to build local conservation partnerships. The FCAT (Fundación para la Conservación de los Andes Tropicales) field station in Ecuador is run by local people who then work with international universities and scientific partners to develop questions and carry out research. It is an effective model of socially informed conservation. Ranger stations in Cross River National Park (Nigeria) codeveloped questions with local communities. After the local agricultural community noted changes in climate that made their practice of burning their fields much more dangerous (rain used to be reliable at the time of year when fields traditionally were burned; it is no longer), the field station created fire danger models from their weather tower data to help schedule safe burning. Bouamir field station (Cameroon) used data from the field station to map genomic vulnerability between diverse taxa under future climate change, which they bring to governmental meetings to inform their conservation policies. They have also worked with local partners to document and pass on multigenerational knowledge to youth, and research ebony conservation methods with local partners. Through this kind of work, field stations become a pipeline for local communities to engage and build their management capacity.

The final topic that the panel discussed was the future of field stations, the resources they need and ways they can continue to grow their impact:

- Government buy-in when establishing new stations or scaling up existing ones, it is essential to be working in partnership with local and national governments from day one to get funding, permits, and to maintain goodwill.

- Global coordination between field stations and policymakers: field stations are in a unique position to be highly qualified on-the-ground partners for achieving GBF targets. For example, a lot of money is going into tree planting as a method for carbon sequestration, but there are not a lot of efficacies. Field stations could be tapped to develop and test regional-level methods in a coordinated, global-scale way, and their data could be streamlined through GBF reporting mechanisms.

- Increased clarity about the value proposition of field stations: we ought to talk more and more publicly about the holistic benefits of field stations, both their research potential and capacity building potential. There is a need for a more standardized business model for field stations, one that more explicitly discusses the value proposition they offer to reduce the individual burden for each station to reinvent the wheel. If field stations were to work together on fundraising efforts, they could do it more efficiently, and potentially establish an endowment across stations.

- Scientific collaboration: standardize protocols to facilitate data sharing between areas and establish fellowships for scientists and students to travel between stations to facilitate information sharing, cross-training, and innovation.

Map depicting reduced forest loss near field stations, based on the study by Epply et al. (2024), presented during the Field Stations session at COP 16.

If you run a field station, and you would like to be connected to this network, please contact Claire Bandet at bandet@nullsas.upenn.edu.

Disclaimer: Opinions are solely those of the guest contributor and not an official ESA policy or position.