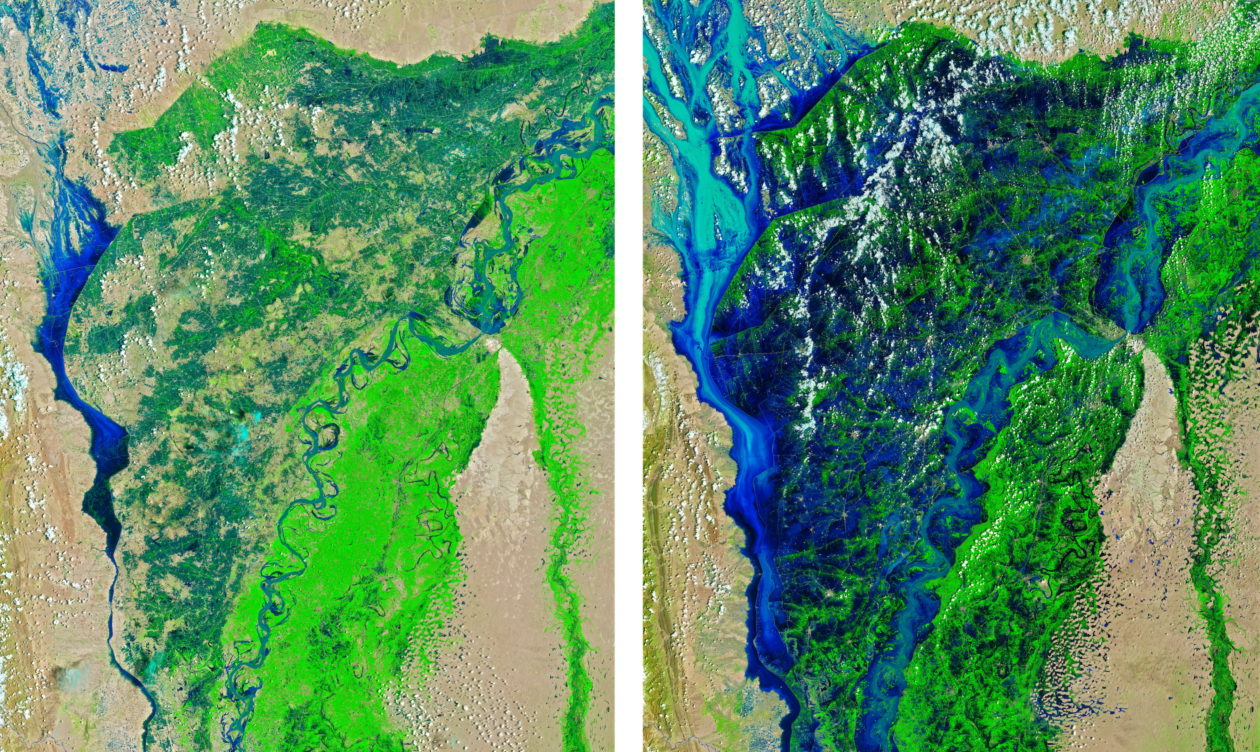

Last summer, from June through August, Pakistan endured extended intense rainfall—exacerbated by climate change—that triggered devastating and unprecedented months-long flooding across the country. The floods killed more than 1700 people, a third of them children; affected 33 million people and displaced 8 million; destroyed more than 2.2 million homes and 4.4 million acres of crops; and cost $40 billion. The people of Pakistan are still reeling from the catastrophic effects of the 2022 floods and the country’s economy is in crisis, even as the 2023 monsoon season is off to a sobering start and the powerful Cyclone Biparjoy is set to make landfall shortly. A year on, here are some hard lessons on the compounding effects of climate and economic injustices, and a call to action from richer countries and international financial institutions.

Five lessons from the floods in Pakistan

- Scientific studies show that climate change was an important contributing factor to these floods. A World Weather Attribution study from an international team of scientists found that ‘…the 5-day maximum rainfall over the provinces Sindh and Balochistan [which were two of the worst affected provinces] is now about 75% more intense than it would have been had the climate not warmed by 1.2C.’ A more recent study found that the intense multi-day rainfall was associated with two atmospheric rivers drawing moisture from the Arabian Sea. It also found that ‘The southern provinces of Pakistan received more than 350% of average precipitation in July and August based on the 2001–2021 mean.’ These floods came soon after the nation had experienced an intense heatwave, made 30 times more likely because of climate change. Science is also clear that climate change will continue to make these kinds of disasters more likely and/or frequent, highlighting the urgent need to invest in resilience measures that will better protect people, livelihoods, housing and infrastructure. Pakistan is responsible for just 0.3 percent of cumulative global carbon dioxide emissions and yet is bearing this terrible toll from climate change caused primarily by emissions from richer nations and fossil fuel companies.

- Climate-caused disasters have a disproportionately harsh impact on the poorest people. According to the World Bank, the floods have forced as many as 9.1 million more people in Pakistan into poverty, increasing the nation’s poverty rate by 4 percent above the 2018-19 poverty rate of 21.9 percent. Many of the hardest-hit areas already had high rates of poverty and children suffering from malnutrition. In the wake of the floods, the needs are acute. A March 2023 report from UNICEF noted that, ‘An estimated 20.6 million people, including 9.6 million children, need humanitarian assistance.’ Meanwhile, 1.8 million people were still living near stagnant floodwaters eight months after the floods. UNICEF also noted that ‘The prolonged lack of safe drinking water and toilets, along with the continued proximity of vulnerable families to bodies of stagnant water, are contributing to the widespread outbreaks of waterborne diseases such as cholera, diarrhoea, dengue, and malaria.’ The World Health Organization called the floods ‘the perfect storm for malaria,’ with the nation experiencing its worst outbreak in the last fifty years.

- Pakistan is trapped in a vicious debt spiral, pulled downward by a climate disaster and an economic crisis colliding with an unjust global financial system. Massive crop, livestock, and infrastructure losses caused by the floods, the global energy crisis triggered by the Ukraine war, a fiscal crisis, and political uncertainty have together contributed to record inflation levels in Pakistan. The country is on track for GDP growth of 0.29 percent in FY23, down from 6.49 percent in 2021. In the wake of the floods, the nation has also seen its credit rating repeatedly downgraded, making it harder for it to recover and pay off its loans. And the IMF is imposing draconian fiscal adjustment measures on the heavily indebted and struggling nation as a precondition for releasing prior bailout funding, pushing its economy further into crisis. Without the IMF funds, Pakistan may be forced into defaulting on its loans within months, compounding the misery for its people. The bottom line is that the international financial system must be reformed to better serve the needs of the poorest people, and nations hit by extreme weather events should have options for immediate debt relief and greater access to grants and concessional loans. The worsening and inequitable impacts of climate change make the need for these reforms even more urgent.

- The global community’s response has fallen well short of what’s needed. Pakistan’s flood response plan is still significantly underfunded. A January 2023 international conference aimed at raising funds for climate resilience in Pakistan resulted in over $10 billion in pledges—but about 90 percent of that is in the form of loans that will become available over the next three years and must be repaid. Pakistan’s plight is a terrible one and richer nations simply must step up to do more to help it on its long road to recovery, as must the World Bank and IMF. Meager and uneven post-disaster humanitarian aid and expensive loans are far from sufficient, and will leave millions of people suffering for years to come.

- Addressing climate Loss and Damage fairly must be a top priority at COP28. At COP27, Pakistan led the urgent and moral call for the establishment of a Loss and Damage Fund to address extreme climate disasters, which richer nations reluctantly agreed to. This year, at COP28, nations must reach agreement on the details needed to operationalize the L&D Fund so that it can be resourced soon thereafter, and climate-vulnerable countries can start to receive the funding they desperately need and deserve. The advance work done by the Transitional Committee on Loss and Damage is critical to securing progress ahead of time so that there is a successful outcome at COP28.

A call to action

Unfortunately, the floods in Pakistan are just one of many climate-driven disasters that have already harmed people around the world—and the world will see many more as the climate crisis worsens. The global community must do more to sharply cut the heat-trapping emissions fueling these extreme events, and also invest in closing the adaptation gap, especially in frontline communities struggling with poverty and the repeated onslaught of disasters.

The Biden-Harris administration should champion reforms to international financial institutions that will go a long way toward making their lending more aligned with climate and sustainable development goals. This is a critical piece of a broader agenda that includes the U.S. delivering on its pledge of $11.4 billion per year in climate finance by 2024. Later this month, President Macron of France will be hosting world leaders at a Summit for a New Global Financing Pact, another opportunity for reforming the global financial system to deliver on the stated goals of ‘fighting inequality, climate change and protecting biodiversity.’

Richer nations like the United States, which are responsible for a majority of global heat-trapping emissions to date, have a unique responsibility to contribute their fair share to sharp cuts in emissions and climate finance. Fossil fuel companies, whose products are directly responsible for climate change, must also be held accountable and contribute to funding to address climate damages. And the international financial system must undergo long-overdue deep reforms to be fit for purpose in a world where climate change is driving more people into poverty and more countries into unsustainable levels of debt.