$4 billion transmission line to deliver Canadian hydropower to New York illustrates tradeoffs in the energy transition.

The Champlain Hudson Power Express transmission line will stretch on the bottom of Lake Champlain. Photo courtesy of John Virgolino/Creative Commons

By Zachary Matson, Adirondack Explorer

This story is re-published with the permission of Adirondack Explorer, where it was originally published.

The large boats will prowl Lake Champlain all day and all night for five months. Barges up to 300 feet long and 90 feet across will carry 12 miles of spooled electrical cable, navigation equipment, a tall crane and a specialized crew. They will drop the cable 4 feet deep in their wake and cover 2 miles a day. The underwater installation will stir up sediment, displace bottom-dwelling creatures and alter the lake’s ecology.

Then the boats will be gone.

“I call it a one-time disturbance,” said Tim Mihuc, a professor of environmental science at SUNY Plattsburgh.

The extraordinary activity will leave behind a hidden thread of power delivering a near-constant flow of energy from manmade reservoirs in Quebec and Labrador to Queens, effectively an Adirondack Park-sized battery projected to provide about one-fifth of New York City’s massive electricity needs in the coming decades. Construction may start in a few months and the cable could be laid in 2024 as part of a major transmission line called the Champlain Hudson Power Express.

Financed by one of the world’s richest private equity firms, The Blackstone Group, the CHPE is championed by its supporters as essential to unwind New York’s reliance on carbon-spewing fossil fuel and meet a 2040 target of emissions-free electricity. The project’s opponents denounce it as a green-in-name-only risk built on a legacy of mistreatment of Indigenous peoples and continuing ecological harm to Canadian rivers, one that boxes out New York energy producers.

The project, announced in 2010, is backed by scores of elected officials, including New York Gov. Kathy Hochul. Securing state and federal permits, in 2013 and 2014, CHPE generated thousands of comments to the New York Public Service Commission and a promise of a $117 million trust fund to support environmental restoration.

The commission in April approved a 25-year state contract offering billions of dollars to Hydro-Quebec, a corporation tied to the Quebec government, for delivering renewable energy. The contract enables developers to move forward with construction this summer and potentially energize the transmission line by the end of 2025.

Opponents have raised concerns about the project’s impact on drinking water supplies from the Hudson River, fish that spawn in the Hudson estuary and market share of New York-based energy producers.

The project’s winding path underscores the grinding pace and tough choices of building new energy infrastructure as the state transitions from fossil fuels.

Emissions-Free Electricity by 2040

In the 2019 Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, New York committed to a set of ambitious electricity targets: 70 percent from renewable sources by 2030 and 100 percent by 2040.

The state still has a way to go. In 2020, 27 percent of the state’s electric load was met by renewable sources, the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority reported. That year, electricity users in the state consumed around 150,000 gigawatt-hours with a third of the use in New York City.

The state in 2020 produced around 130,000 GWh of electricity, 43 percent from gas and oil power plants, 29 percent from nuclear plants and 22 percent from hydroelectric sources, according to New York Independent System Operator (NYISO) data.

Wind accounted for 3 percent of the state’s production, solar less than 1 percent. The state imported over 30,000 GWh, including around 8,500 GWh from Hydro-Quebec on a pair of existing transmission connections in the North Country.

The state’s electricity network has been called a “tale of two grids.” Already, 90 percent produced upstate is emissions free, but in New York City around 80 percent comes from fossil fuels. Transmission constraints limit the flow of upstate renewable sources to the city.

State officials cite a pipeline of approved large-scale renewable projects expected to deliver 54,000 GWh of electricity and lift the state’s use of renewable sources over 60 percent by 2030.

“New York’s renewable and environmental goals are driving profound changes on the electric system,” NYISO reported last year.

Drawing from the enormous energy portfolio of Hydro-Quebec’s 62 generating stations, the proposed CHPE line is projected to transmit around 10,000 GWh of energy to New York City each year, about 20 percent of the city’s estimated electricity needs in 2026.

“To be able to achieve these targets by 2030 and 2040, you need to get new transmission services into the city to bring the renewable energy in,” said Donald Jessome, CEO of Transmission Developers Inc., the company building CHPE. Existing dams and reservoirs qualify under the state’s renewable standards.

CHPE proponents say the project will help wean New York City off oil and gas generating facilities switched on during periods of high electricity demand, so-called “peaker plants.” The city’s 19 peaker plants produce a disproportionate share of emissions and pollution.

The plants are in low-income areas and contribute to health problems among people of color. Around 750,000 city residents live within one mile of a peaker plant, and 78 percent of them are either low income or people of color, according to a 2021 report by the Peak Coalition, a group that advocates for environmental justice. Reliance on the peaker plants has only increased since the state closed the Indian Point nuclear plant north of the city last year.

Contractor Caldwell Marine used a special barge to lay electric cable under Lake Champlain for a project connecting Plattsburgh, New York, to Vermont in 2018. Photo by Caldwell Marine

A Big ‘Green Battery’

Quebec Premier François Legault has said he hopes the province will become the “green battery of North America.” The scale of Hydro-Quebec’s water resources underscores the potential role it can play in serving New York’s energy needs.

The hydro company in recent decades has aimed to expand its exports in American markets, supporting major transmission corridors in New York and New England. But those efforts have been stymied by resistance on multiple fronts.

The developer behind a proposed transmission line from Quebec through New Hampshire in 2019 dropped the plan amid resistance similar to what CHPE is facing. Maine voters in November rejected a transmission line already under construction to deliver Canadian hydropower to New England.

Still, energy economists and many environmentalists see the existing Canadian reservoirs as a key tool to balance wind and solar power sources in New York.

Wind energy is so variable that over some stretches the state’s combined wind fleet produces 5 percent or less of its overall capacity. Solar as of 2020 represented less than 1 percent of electricity produced in New York. Hydro-Quebec claims it will deliver electricity at 95 percent of its capacity.

“The current decision in front of New York is a slam dunk to take existing assets and utilize them better,” MIT energy economist John Parsons said.

Parsons and his colleagues at the Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research in a 2020 paper described how Quebec’s hydro resources can help New York balance energy consumption, moving toward a two-way trade of electricity between the state and the province.

When solar and wind generators are overproducing in New York, they can send excess energy to Canada, allowing Quebec to maintain its reservoirs. When New York producers are falling short of demand, the hydropower can flow into the state, cementing system-wide efficiencies in both countries. If New York relied entirely on in-state wind and solar, Parsons said, it would have to overbuild capacity to accommodate fluctuations in production.

Detractors argue Hydro-Quebec’s battery is not so green.

When forests and wetlands are flooded to create a new reservoir, they release a wave of greenhouse gas emissions that initially rival the emissions produced by gas-burning power plants, according to a 2011 study of a Hydro-Quebec reservoir. Those emissions slow over time and across the lifespan of a reservoir average out to roughly the emissions produced by wind and solar installations, according to a 2020 study that estimated the lifecycle emissions of Hydro-Quebec reservoirs.

The reservoirs also activate mercury in the soil, setting off a pulse of dangerous methylmercury that accumulates up the food chain. People who rely on fish from areas flooded by dams are at increased risk of methylmercury absorption, which has been shown to harm fetal development.

Dams wreak massive ecological and social changes across the planet.

Studies estimate that between 40 million and 80 million people worldwide have been displaced by dam construction in the past century, and nearly 500 million people have been affected by changes to fisheries and river flows. An estimated 3,700 major dams are planned or under construction across the globe.

Annie Wilson, an activist with the North American Megadam Resistance Alliance, said dams cause wide-reaching environmental and social harm. “We have to restore our ecosystems as much as possible, and streams, rivers, those are the veins of our Mother Earth,” Wilson said. “These dams are not allowed to be built in the United States anymore.”

She cited a Johnny Cash and Peter La Farge song that tells the story of the Kinzua Dam, which flooded Seneca Reservation lands in 1965 and left behind a reservoir stretching north across the New York state line. “The earth is mother to the Senecas, they’re trampling sacred ground,” Cash sang.

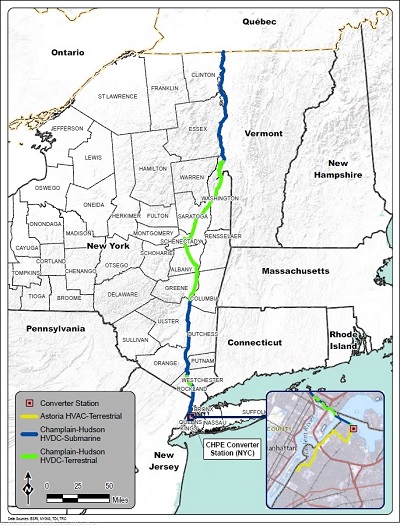

Map of the CHPE transmission line route. Blue lines indicate where the line will be under water.

A Question of Lake Bottoms

The CHPE line, a pair of six-inch high-voltage direct current cables with the capacity to transmit 1,250 megawatts, would connect to Hydro-Quebec’s sprawling transmission network outside Montreal, crossing the border via the Richelieu River and Lake Champlain.

As the line stretches beneath Champlain, it would pass through the Adirondack Park, winding among the islands east of historic Valcour Island. It would skirt Split Rock Mountain Wild Forest.

At Split Rock, steep ridges dark with evergreens jut into the lake. A mix of hemlocks, pines and cedars toes the shoreline. An eagle in early spring rested in a nest perched atop a dead tree on the shore of a bay.

Adirondack advocacy groups at the project’s outset urged state officials to evaluate whether Article 14 “forever wild” protections extend to the bottom of Lake Champlain.

“We believe a new attorney general opinion should be sought … to lessen the chance that any citizen of the state file a lawsuit stopping the project as it may violate Article XIV of the State Constitution,” wrote Allison Buckley, then the Adirondack Council’s conservation director, in comments submitted in 2012.

But state officials have been satisfied with a 104-year-old attorney general opinion. It allowed the Fort William Henry Hotel to run a cable on the bottom of Lake George.

Public Service staff in a 2012 filing dismissed concerns that granting property rights under Lake Champlain would be unconstitutional. Whether the lake-bottom route “is part of the protected Forest Preserve is a legal question that has been answered repeatedly in the negative,” the PSC wrote.

The filing provided one citation in support: the 1918 opinion of Attorney General Merton E. Lewis. State officials cited the same opinion in response to questions from the Adirondack Explorer. Lewis opined that because the state owns the land under navigable waters “as sovereign” rather than “proprietor” they were not intended to be included in the forest preserve when the protections were adopted at the 1894 Constitutional Convention, at which Lewis served as a delegate.

“It seems absurd to speak of preserving the lands under the navigable waters of the forest preserve counties as ‘wild forest lands,’” Lewis wrote.

Two administrative law judges tasked with overseeing the project in 2012 noted the Adirondack Park Agency “supports the [proposed project] and agreed to the routing of the transmission line in Lake Champlain.

The judges wrote that Lewis’ 1918 opinion found the power to convey state lands under navigable waters existed. They noted the limited environmental impacts documented in assessments of the project and determined “that placement of the cable underwater in Lake Champlain should not impair the lake’s ‘wild character’ nor interfere with its natural qualities or recreational uses.”

Department of Environmental Conservation lawyers in 2013 agreed, but added that “a thorough analysis of the New York Constitution’s Article 14 ‘forever wild’ clause is beyond the scope of this proceeding and is far too complex to be summarized in an overly broad manner.”

The DEC’s support for the project concluded: “This proceeding is not the appropriate venue to litigate constitutional claims premised on the ‘forever wild’ clause.”

In 1996, Attorney General Dennis Vacco, the last Republican to hold the office, took a different view about lakes and forest preserve. He asserted that Raquette and Moose lakes “are indisputably part of the forest preserve” and advised against granting permits for lake-bottom electrical lines to a handful of private homes.

David Gibson, of Adirondack Wild: Friends of the Forest Preserve, said questions about where the forest preserve extends underwater have been “swept under the rug all of these years.”

Rob Rosborough, an attorney who has worked on Adirondack cases at the state Court of Appeals, said it was a common state to avoid analyzing Article 14 issues and noted officials could have pursued a constitutional amendment if necessary.

“What they try to do in every case is take the easy way out and hope no one challenges them,” Rosborough said.

Under the Lake

State and federal agencies have found minimal environmental impacts associated with the CHPE project, but ecologists who focus on Lake Champlain said construction could alter fish habitats and food webs. Developers established the $117 million environmental trust fund to support monitoring and restoration projects in Lake Champlain and the Hudson, Harlem and East rivers.

A governance committee composed of representatives from CHPE, state agencies and environmental and community groups will direct the fund.

Ellen Marsden, of the University of Vermont Wildlife & Fisheries Biology Program, said she anticipates cable installation will affect Champlain’s shallow southern section most.

Marsden said sediment disturbed by water jetting and dredging will change fish habitat. Some fish use the natural substrate for burrowing while others want rocky or sandy areas for spawning and foraging. As suspended sediment resettles, it will bury and alter these habitats, causing problems for the fish that breed and feed there. The long-term effect of degraded spawning areas could ripple through subsequent generations.

Marsden is also concerned about silt stirred up by turbulence. It can damage fish gills and insects in their larval stages. Eggs in nests could be suffocated by sediment. Cloudy water could prevent sunlight from reaching aquatic vegetation, limiting photosynthesis. Threats to food sources at the primary trophic level could trigger impacts throughout the food web.

The trust fund would be used in Lake Champlain for fish population surveys, fish habitat assessments, habitat restoration and aquatic invasive species management. Marsden emphasized the importance of collecting data before construction.

Once pre-construction conditions are known, the project’s environmental impact can be measured. Restoration responses could range from clearing altered habitat of sediment by controlled blasts of water or constructing new habitat nearby–such as building a reef from loose rocks. Another management response could be to reduce fishing in those areas to enable ecosystem recovery.

Developers contracted with the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum to plot a route underwater that avoided shipwrecks and other cultural resources in the lake.

“There’s a lot down there,” said Chris Sabick, director of archeology and research at the museum. “We see our role in these types of projects as a continuation of our efforts to help preserve these resources.”

Developers also negotiated more than a dozen agreements along the proposed route, seeking reduced tax payments over the next 30 years, while guaranteeing payments to local governments and school districts.

In Clinton, Essex and Washington counties, developers estimated a combined construction cost of nearly $700 million, over $4 billion for the entire project. Such agreements with these three counties outline projected tax payments of $470 million over the next three decades, including nearly $270 million in Washington County. The counties agreed to exempt developers of over $40 million in mortgage and sale taxes.

Karl and Lani Ohly’s farm overlooking Lake Champlain would be beside the path of the power line. Photo by Zachary Matson/Adirondack Explorer

For or Against

When Lani and Karl Ohly moved from the Ohio River Valley, they looked for clear skies, clean air and a lack of industrial development.

They found a new home on over 400 acres in Putnam Station perched above the southern narrows of Lake Champlain. The farm site is where they run a bed and breakfast, the Inn on Lake Champlain.

“The Adirondacks is a more and more relevant model in terms of protecting the benefits for individuals who live here,” Karl said. “You experience one side of the [industrialization] coin, and you realize how valuable the protections are.”

They oppose CHPE, which would go by their property. The couple said they think the plan could be a violation of deed restrictions that require the road right-of-way be used only “for the purpose of a road,” arguing the transmission line does nothing to benefit the residents of Putnam.

They are also concerned about precedent. “How many lines will be allowed to come through the Adirondack Park?” Lani asked. “The Adirondack Park has not been a place where private corporations can just crisscross the park at any price.”

CHPE faces opposition further down the line.

The Hudson Riverkeeper, a nonprofit focused on protecting the river, agreed to a 2012 settlement, but in the past year has sought to block the project, highlighting concerns about Hudson River fisheries, drinking supplies and the emissions associated with hydropower. The Sierra Club opposes CHPE for similar reasons.

“We think putting in more transmission from upstate to downstate is a good thing. The thing we really disagree about is Canadian hydro,” Riverkeeper attorney Richard Webster said.

Gavin Donohue, president of the Independent Power Producers of New York, said utility ratepayers will incur cost increases to pay for the renewable credits. The state should be encouraging projects by state generators, he said.

“When we have abundant renewable projects proposed within New York’s borders, why are we giving money to a Canadian utility to accomplish our goals?” Donohue asked.

Opponents contend that the state can do more to bolster efficiency, expand rooftop solar and improve transmission to in-state projects.

Some environmental groups, including the Nature Conservancy and the New York League of Conservation Voters, support CHPE and emphasize moving to emissions-free electricity as soon as possible. So do activists focused on the pollution from New York City’s oil and gas plants. Business groups, including the North Country and Adirondack chambers of commerce, support the project, and major unions hail the jobs it promises.

Ryan Calder, a professor of environmental health and policy at Virginia Tech, studied and documented the surge of methylmercury caused by new reservoirs in Labrador. His research is often cited by CHPE detractors as evidence of widespread methylmercury poisoning across Canadian reservoirs. “I know that people say that, l wish they wouldn’t,” Calder said.

The impacts of renewable projects should be examined and mitigated, Calder said, but a transition to new energy sources will require difficult tradeoffs. Sometimes a less-than-ideal project is better than continuing the use of more harmful energy sources, he said.

“I agree it’s important to consider environmental impacts pretty broadly, but you have to consider them in the context of alternatives,” Calder said.

Surveyors have started to chalk out marks in front of the Inn on Lake Champlain. The road bends at the old Victorian house and passes a large barn built in 1900. Karl Ohly is swapping old beams with hand-milled replacements. If CHPE becomes a reality, for 50 years or more electrons generated by dams 1,000 miles north will zip underground past the old barn to help turn on lights, charge cars and power the world’s financial system in a city 250 miles south.

Zachary Matson is an Adirondack Explorer reporter specializing in water issues. Dana Holmlund contributed to this report.