Updated Nov. 21 to correct Jo Field’s name.

Climate change is putting mounting pressure on New England states: drought conditions interrupted by intense precipitation events, invasive pests killing ash and hemlock, sunny day flooding in coastal towns, increased public health burdens due to high heat days. Considering these impacts and more, action to build resilience needs to be a priority of forward-looking leaders. So how are New England states and their leaders doing?

I was fortunate to mentor two emerging scientists to answer this question. Through a partnership between UCS and the University of New Hampshire Sustainability Institute Fellowships program, Jo Field and Miriam Silverman Israel assessed climate action progress in each of the six New England states: Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island.

Jo and Miriam brought their social science expertise to bear by interviewing energy and adaptation experts in every state and conducting secondary research over a period of ten weeks.

How do we measure New England’s climate progress?

We agreed to organize their assessment using 15 principles identified in the UCS report Towards Climate Resilience. Those principles fall into three buckets: policy life cycle, long-term planning and policy revision, and equity and community needs.

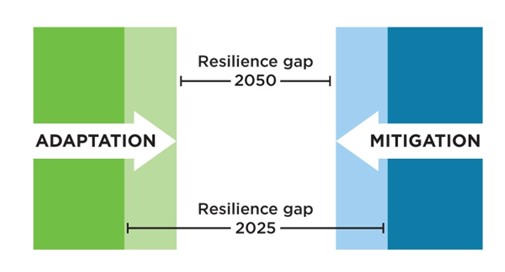

Once organized, they determined the extent of New England states’ resilience gap. The resilience gap is defined in Towards Climate Resilience as the degree to which people, communities, economic sectors, etc. are unprepared for the climate-driven pressures and impacts they face, leaving them open to harm.

Because of decades of inaction, narrowing the climate resilience gap requires simultaneous actions on climate mitigation and adaptation. State and local governments must at the same time implement policies that reduce heat trapping emissions, thereby helping to slow the pace of climate change, and implement policies–to which we are already committed–that prepare us for the impacts of a changing climate.

States demonstrate trends, some progress…and outright inaction

The fellows presented their New England State Climate Action Assessment to peers and faculty in the UNH Sustainability Institute, to UCS scientists and analysts, and to members of our Science Network in our New England webinar earlier this fall. Readers will find important trends in the assessment and learn a great deal from the fellows’ analysis and annotated bibliography.

Jo Field and Miriam Silverman Israel recounted four questions that were posed in these presentations, and answer them here:

What is the biggest takeaway from your assessment? Did anything surprise you?

JO FIELD: The biggest takeaway for me is that across the region, including in states which emerged as “leaders,” there is a lot more work to be done, particularly around addressing community needs and inequities. In every state we assessed, we saw major shortfalls in how states are addressing existing inequities, and an overall lack of work to protect what people cherish, to ensure the costs and benefits are equitably shared, and to maximize accountability and transparency around state action. States are starting to talk more about commitments to address inequities and injustices, but aren’t necessarily following through on their words.

MIRIAM ISRAEL: A big takeaway for me is the importance of local government and the need to build capacity equitably within a state. We found that municipalities or regions with more resources were better able to mobilize their own funds or apply for grants and state funding. Lower-income areas, that are often more at risk of climate impacts, do not always have the capacity to access these types of assistance or initiate resilience projects. As states ramp up resilience efforts, there needs to be a focus on local solutions and increasing the capacity of local leaders, to make sure resources are being distributed equitably throughout a state. This is often talked about in the context of environmental justice communities, but it is important to notice how the local government structures within states also play a role in the distribution of resources and the overall level of ambition for states.

Is New England on the right track?

JO FIELD: I’m hesitant to say whether I think New England is on the right track or not. If you were to look at a national scale, it would be easy to think that the New England states are leading the charge and are putting in the work needed to build climate resilience. But New England still has so much more to do to become adequately prepared to cope with the projected impacts of climate change. To be on the right track is to be consistent in your policies and actions, to think ahead and plan for the long-term, to carry out what you say you will, and to really act in ways that protect your constituents and what matters most to them.

MIRIAM ISRAEL: In some ways, New England is on the right track since there are a lot of dedicated people in government, advocacy, the private sector, and other fields who are working on mitigation and adaptation in New England. Yet, states need to be making faster progress to reduce emissions and really come to terms with the potential impacts of climate change, an issue still very politicized across the region, which has prevented conversations around things like the potential need to relocate away from coastal areas or floodplains, or the potential damage to industries like fishing or tourism. Building true climate resilience requires an honest understanding of what climate impacts you need to prepare for and who will be most at risk. There is still a lot more that New England states could be doing to build this understanding and ensure that solutions are being implemented at an adequate scale and in an inclusive way.

Within the New England states you assessed, is there one leading the pack, or one that seems to be falling behind?

JO FIELD: We found a couple of states were leading the pack, however the biggest outlier was really the fact that New Hampshire is falling significantly further behind the rest of the New England states. The more shocking part of this is that the state government has publicly acknowledged that they don’t have the same level of climate ambition as their New England neighbors, and they don’t view this as a shortfall. New Hampshire lacks the long-term vision, the systems-thinking approach, and the commitment to push mitigation efforts that neighboring states have worked towards.

MIRIAM ISRAEL: Agree with Jo! I would add that although these problems can seem overwhelming and complicated, New England has a lot of examples of success. Despite only seriously considering climate change as an issue after 2018, Maine has achieved remarkable progress in a short period of time and makes clear that it is possible to work towards climate resilience quickly and effectively.

If you had one message for incoming state policymakers, what would it be?

JO FIELD: If climate change is not already a priority in your government, make it one. We know that climate change is costly, regardless of the route we choose to take, but we also know that the costs will be significantly greater–economically, ecologically, socially–if we drag our feet and take a business-as-usual approach to dealing with it. Climate change is already here and if we fail to act to prevent further climate change through mitigation efforts, or to reduce the risk of harm caused by inevitable climate impacts through adaptation efforts, the costs will become far greater and far more devastating to your constituents.

MIRIAM ISRAEL: Legislators and governors need to be thinking in the long term and not just looking ahead to the next election cycle; climate change is the defining problem of not only our time, but for all people in the future. Achieving climate resilience is going to require changes that might be politically difficult in the short term but that are necessary to ensure a livable planet for us and all future generations. By modelling strong leadership and making clear to constituents why this issue is a priority, legislators and governors have the opportunity to enact transformational change and contribute to a more sustainable, more just society.

Jo Field is pursuing her PhD in Natural Resources and Environmental Studies at the University of New Hampshire. She gained her MS in Science Communication from Cardiff University in Wales. Her graduate research focuses on the roles of community engagement and public participation in climate resilience.

Miriam Israel is a dual-degree student at The Fletcher School at Tufts University and the Harvard Divinity School studying international environmental policy, human security, and the role of faith communities in combatting climate change. Prior to graduate school, she worked at a refugee resettlement agency as well as at the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs, focusing on inclusive governance and political organizing.