In their new study, Allen et al. present a case study in Northern Ireland (NI) showing how selective culling can be less disruptive to badger social structures than indiscriminate culling. This method could be an effective and more socially acceptable means of controlling bovine tuberculosis (bTB) in wildlife.

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has raised consciousness on the issue of human disturbance of ecosystems and how this may cause outbreaks of pathogens. ‘Spillovers’ from infected wildlife, causing disease in humans and domestic livestock, can wreak public health havoc and economic disruption.

These zoonoses have a complex epidemiology involving pathogens with wide host ranges. The latter can facilitate spread across dense contact and movement networks of multiple hosts – a Gordian knot that public health officials seek to unpick while advising policy makers on possible interventions.

Sometimes, advice can seem counterintuitive, be dependent on local contexts or can change as time passes and evidence mounts.

Such complexity is not the sole preserve of the pathogens that cause global pandemics, however.

bTB caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium bovis, can infect cattle, an outcome that, for reasons of public health and trade, requires culling and imposition of movement restrictions on infected farms. The economic burden is substantial – more than £99 million of public money is spent annually in Great Britain (GB) on control measures.

Adding to the difficulty of eradication, is M. bovis’ capacity to infect one of our most charismatic wildlife species – the European badger (Meles meles), whose habitat overlaps with pastureland.

Badgers and TB – is culling a black and white issue?

Infection of badgers was first discovered in the mid-20th century and since then, many studies have demonstrated that they can infect cattle and cattle can infect them. Dealing only with the infection in cattle, and not in badgers, is therefore seen as a major impediment to bTB eradication.

Efforts to address bTB in badgers have, until recently, involved some form of indiscriminate culling to reduce the number of infectious contacts between cattle and badgers and therefore drive down cattle disease prevalence.

The results have however, have been something of a mixed bag and contentious. In Ireland, culling reduced the prevalence of disease in badgers and cattle in culling zones. In GB, prevalence of disease also dropped within cull zones but increased at the edges of zones.

The latter was hypothesised to be due to culling-induced disruption of badger social structure resulting in animals moving greater distances, carrying M. bovis with them, and infecting more cattle. In Ireland, while badger social group structure was found to be disturbed, the ‘perturbation effect’ – where this process increased spread of infection – was not observed.

Controversy over the effectiveness of culling reigned and added to the mix was the polarising issue of just how socially acceptable it was to cull such a beloved wild animal. Ideological trenches were being dug.

But was there an alternative? The Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) in NI believed so.

The Test and Vaccinate or Remove approach.

Rather than indiscriminately culling badgers, why not only remove those which you know to be infected, and those which aren’t, you can vaccinate and release? Simulation models suggested that this ‘Test and Vaccinate or Remove’ (TVR) approach, provided social perturbation could be avoided, may be more effective at reducing bTB levels in badgers than vaccination alone.

Crucially, it was likely to be more socially acceptable. Culling fewer, infected badgers is better than culling many badgers of unknown health status.

However, other modelling research using data from GB suggested that selective removal of even small numbers of badgers could induce perturbation – specifically, increasing ranging and causing more social mixing that can lead to reduced genetic relatedness of social groups.

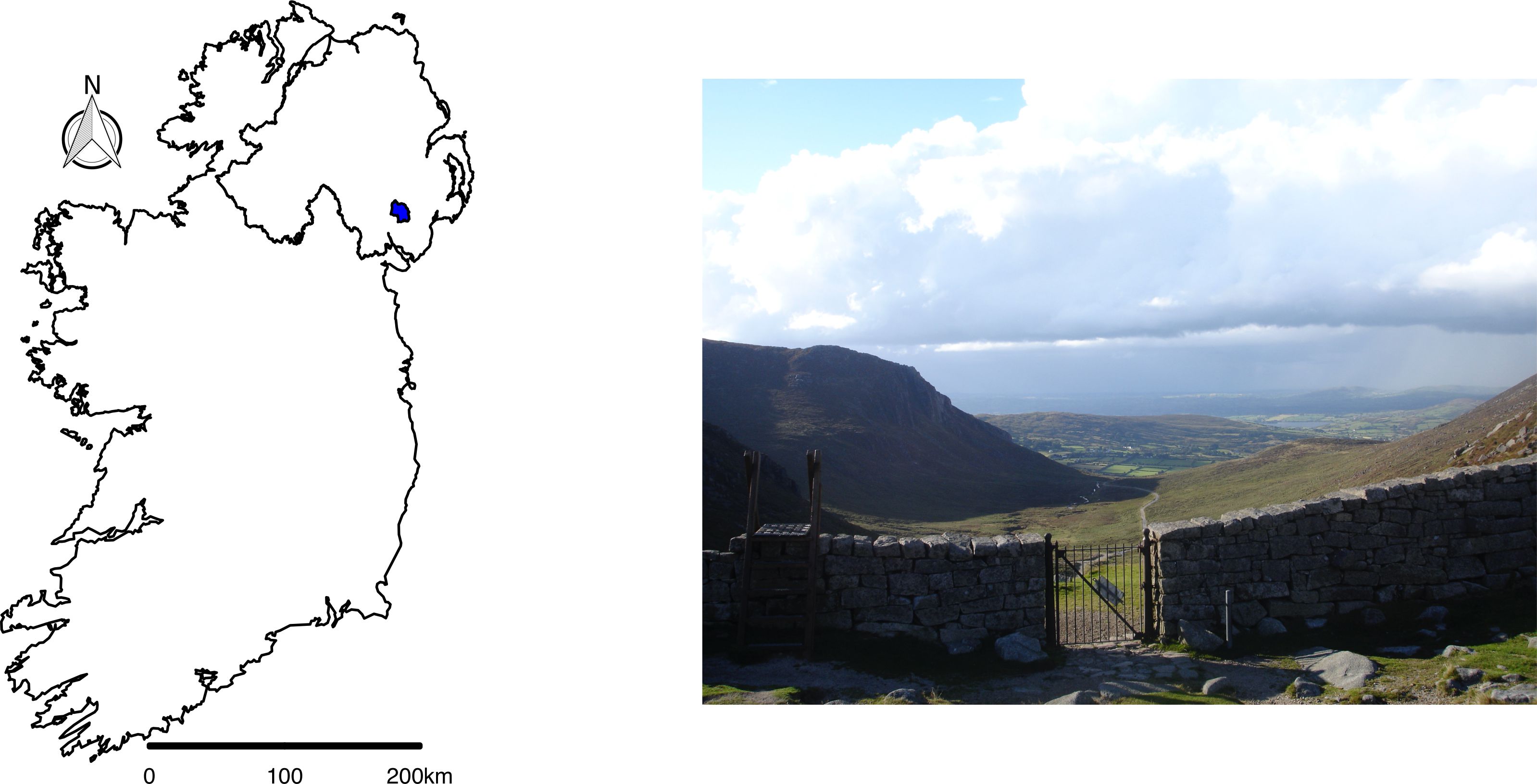

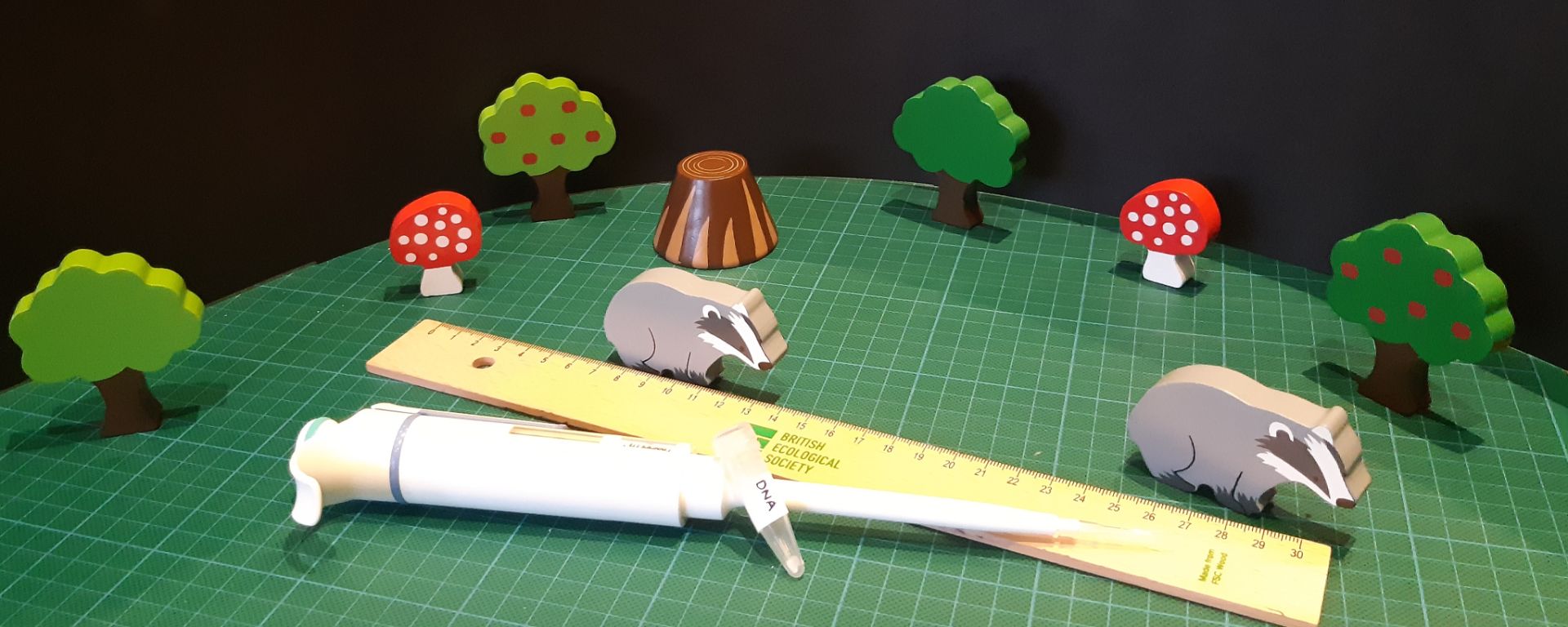

DAERA decided to proceed with a TVR approach in a 100 km2 area in NI. In 2014, a survey was undertaken to determine ecological baselines with badgers trapped at GPS recorded locations, injected with RFID chips for identification, DNA sampled, tested for bTB, vaccinated if negative and then released. In remaining years of the study (2015-2018) this protocol remained the same but for the fact that bTB positive badgers were euthanised.

The data collected gave us an opportunity to assess whether low intensity, selective culling was causing social perturbation. We assessed this using two approaches:

1. Determine how much badgers were moving in the area across all years of the study using a ‘mark recapture approach’. We assembled a dataset of pairs of consecutive captures for unique badgers within each year, across all years of the study. GPS location data from each capture then permitted us to assess the distance moved by badgers between captures. We then modelled whether factors like year of capture, age, sex, season of capture and intensity of culling was affecting the distances moved.

2. Using the genetic profile data we had assembled for all captured badgers to assess the relatedness of social groups and how it varied over the period of the study and in response to intensity of culling.

What did we find?

The TVR protocol of removing only infected badgers resulted in small numbers of badgers being removed and this did not result in increased badger movement. Additionally, our genetic data indicated that social group relatedness remained very similar across all years of the study, only decreasing significantly in social groups that had experienced selective culling.

We therefore proposed that low intensity, selective culling was not inducing widespread social perturbation. Encouragingly, in an independent study of a smaller number of TVR zone badgers fitted with GPS collars, DAERA colleagues had observed that home ranges did not increase in response to culling. Furthermore, prevalence of TB in the badger population significantly decreased over the period of the study.

The evidence points to selective culling using a TVR protocol being an effective policy alternative to indiscriminate culling. Admittedly, local context can be important to outcomes of wildlife interventions to control disease. What works in one place may not be successful in another so taking account of ecosystem difference is important.

This said, the type of landscape and badger population encountered in this study, is very similar to that found throughout GB and Ireland and beyond so the TVR method may have wider utility.

Having seen how the TVR approach can reduce infection in badgers and avoid perturbation, future work is needed to assess the impact on cattle disease prevalence.

Read the full research: “European badger (Meles meles) responses to low-intensity, selective culling: Using mark-recapture and relatedness data to assess social perturbation” in Issue 3:3 of Ecological Solutions and Evidence.

Reblogged this on fizzicalgraffiti.

LikeLike