If you thought the problem of tar sands cleanup had gone away, think again. The government is developing regulations that could allow oil producers in the tar sands to flush their industrial wastewater down the Athabasca River. This week, a group of over 40 scientists and doctors sent Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault a letter in which they urge him to use great caution as he considers these regulations. Let’s explore their four key takeaways.

But first, a bit of background…

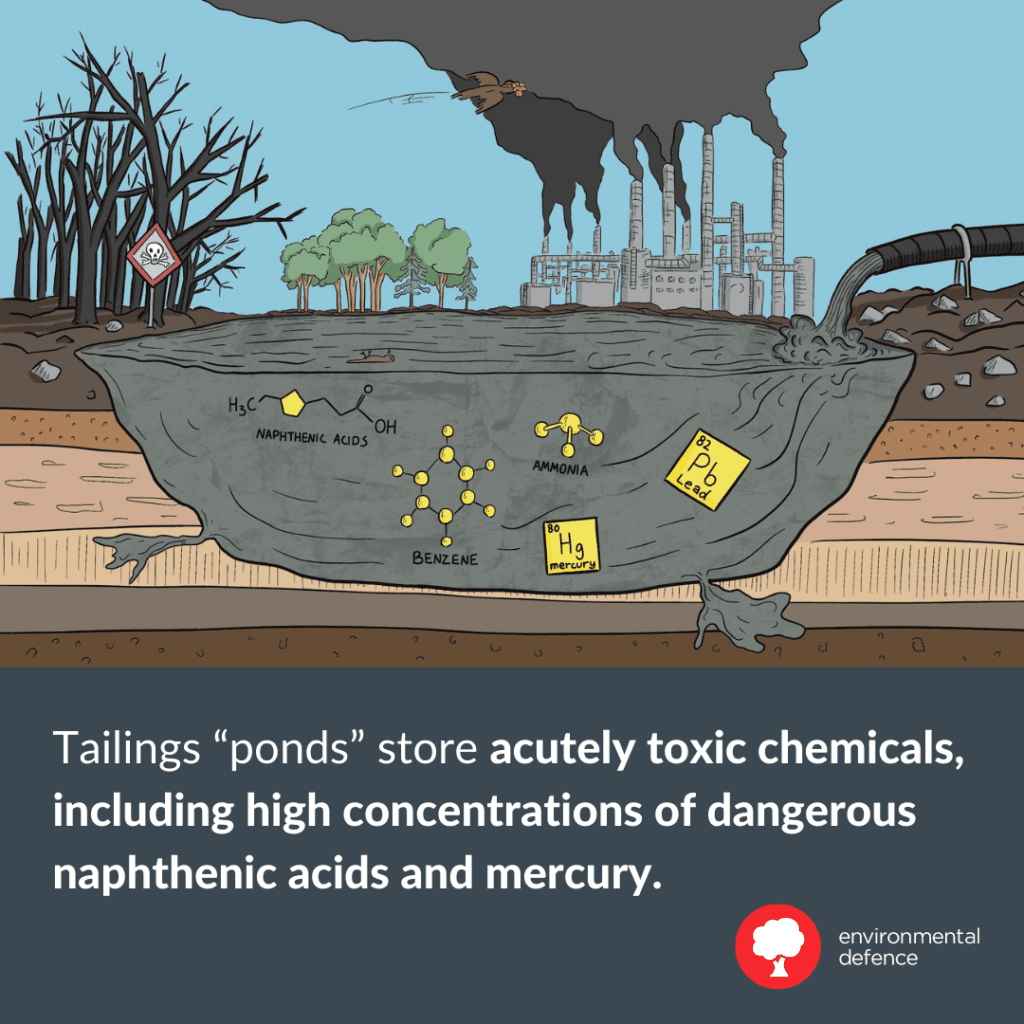

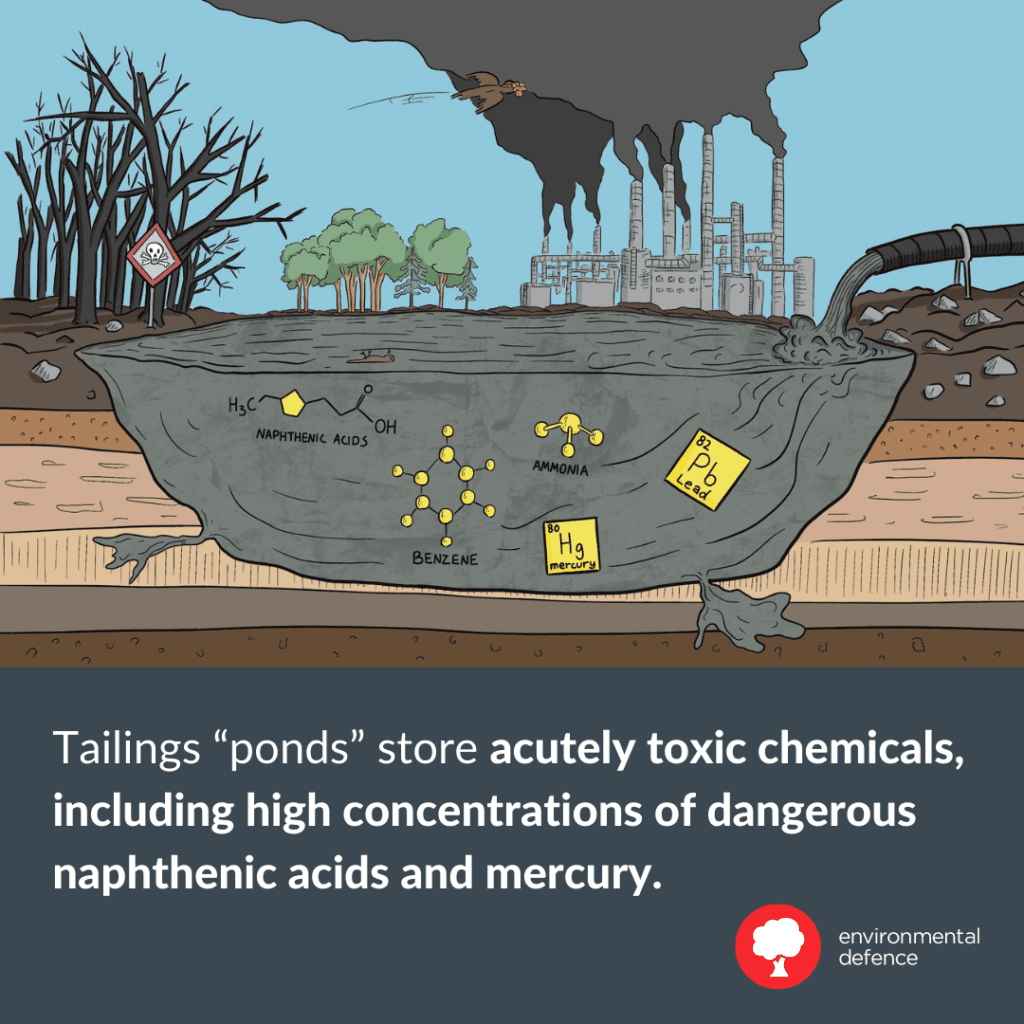

Tailings “ponds” are immense lakes of toxic waste created by oil companies in the Alberta tar sands. They now contain over 1.4 trillion litres of toxic fluid and sprawl over 300 km² – an area 2.6 times the size of Vancouver. The situation has grown out of control, and now Industry is asking the government to allow them to release the tailings into the Peace-Athabasca delta.

Indigenous communities and environmental groups have come out in opposition to this plan, citing serious concerns for the health and safety of downstream Indigenous communities and ecosystems. The Dene Nation passed a resolution at their National Assembly over the summer opposing the release of the tailings into the river, which flows through their territories.

Doctors and academics are now voicing their concerns about the plan. In their letter, the group demands a rigorous and independent risk assessment of the proposed release to be made public and a commitment by the government to ensure any release meets the highest water quality standards.

Now, on to the key takeaways:

Tailings fluids are not your average wastewater

The tailings “ponds” hold chemically complex mixtures unique to the tar sands. Their acute toxicity is lethal to the birds who land on them, and the long-term impact of exposure to tailings water on human and environmental health has been severely understudied. Also, the Athabasca River is already polluted due to oil production and other industrial activities upstream of the tar sands, so there is a lot we do not know about how much pollution the nearby communities and environment are already exposed to.

Recent analysis shows the tailings “ponds” have grown 300 per cent since 2000 and no tailings pond has received a certification that the area has been returned to its pre-disturbed state – a process known as “reclamation.” Therefore, when the industry promises a rapid “treat-and-release” approach after decades of inaction to address the tailings pollution issue, we should ask ourselves what corners will be cut and what, or who, would be sacrificed.

The right approach requires transparency and rigour

The lead authors of the letter are seasoned risk assessors and toxicologists. They have seen numerous industries go through the process of figuring out what to do with their waste. Their letter does not oppose the principle of releasing treated wastewater. Instead, they reject the current approach, fraught with secrecy and siloed conversations, where the wrong people are at the table for the wrong reasons.

The right approach starts with full transparency and data sharing. Currently, industry and government have closed-door conversations. Some impacted First Nations are invited to a separate table where they are not given access to the industry’s plans. Meanwhile, other Indigenous Nations further downstream, such as members of the Dene National Assembly, as well as scientists, conservation groups and public health experts, are kept in the dark.

The current process also puts the cart before the horse. Before developing and engaging affected communities and Nations on regulations for releasing tailings, the government should have made a rigorous and independent risk assessment available to the public. It should answer questions such as:

- What is in the ponds, and in what quantity?

- What is left after the proposed treatment?

- What do we know about these substances, how do they interact with each other, and most importantly, with other substances already in the river?

- What are the substances’ effects – individually and as mixtures – on people, animals and plants? What do we know about the immediate and long-term potential effects of these exposures?

Only with this information in hand can impacted communities and independent experts formulate an informed position on the proposed regulations.

High standards are the bare minimum

The signatories told the Environment Minister that any authorized release must guarantee “no further exposure” for the communities and ecosystems downstream – this is a high standard. It is not enough for treated fluids to have concentrations of dangerous chemicals and substances below the Canada-wide health limits. Instead, the treated fluids must be virtually free of these substances before they are released anywhere.

This high standard is needed because the Athabasca River is already polluted, largely by the tailings themselves that have been leaking and evaporating chemicals for decades in nearby waterways. Other industrial activities further upstream also add to the pollution of the river. Additionally, the communities of Fort Chipewyan and Fort McKay experience an unusually high rate of rare cancers. The Elders of these communities have also noticed a decline in local wildlife. There is also the issue of volume: the tailings contain 1.4 trillion litres of fluids. Any release would have a noticeable and significant impact on the environment.

The government can’t look at a release of tailings water as a single issue. If approved, it would be an additional source of exposure in an already vulnerable and weakened place. We cannot gamble with human and environmental health by adding more toxicity to the mix!

On safety: the burden of proof should be on companies – not communities

In their letter, the group of scientists and doctors ask that the government provide a long list of technical toxicological details that lay out the information required to undertake a rigorous risk assessment. In short, they are asking the government to answer the question: “why should we believe this is safe?”

It is up to companies to prove their plan is safe, not to impacted communities to prove that it is not. So far, downstream Indigenous Nations have been asked to justify their concerns with the plan. But the burden of safety should be on the shoulders of the companies that have profited from pollution and have access to the data – to prove why releasing tailings is safe. Companies do not have an inherent right to pollute, but people have a right to live free of pollution.

Over 40 scientists and doctors have signed the letter, and more experts are adding their names now that the letter is public. There’s no need to be a scientist to voice your concerns about the plan: you can join them in asking Minister Guilbeault not to allow the release: