New work by Arnold and colleagues shows that sustainably grown cacao is a conservation solution which can support both people and nature, and that cacao agroforests and secondary forest can enrich regional biodiversity.

Conservation initiatives have traditionally focused on protecting untouched natural areas. While this is important, we also need to understand how biodiversity can be promoted not as an alternative to human use of the environment, but as part of it.

Our research took place in Trinidad and Tobago, a twin-island nation in the Caribbean. Cacao has been a part of the Trinidadian economy for more than 200 years. Though the industry has declined substantially since the 1800s, there are still many cacao farmers today and much of the land has been shaped by cacao farming.

Recently, abandoned cacao agroforests are being reclaimed for non-intensive harvesting to meet a rising demand for ethically and sustainably sourced chocolate.

To explore how Trinidad’s cacao-influenced landscape supports biodiversity, we surveyed tree and bird assemblages across the north of the island, including those in active cacao agroforests, cacao agroforests at various stages of abandonment, and primary forest.

We found that the cacao agroforests and secondary forests supported just as many bird species as primary forests. These included some forest specialist species, such as collared trogons, long-billed gnatwrens and red-eyed vireos.

Unlike many other forms of agriculture, traditional cacao agroforests have standing trees that form two canopy layers, and often have other agricultural trees like mango and orange mixed in.

The complex three-dimensional structure, and the wealth of fruiting and flowering plants provided can be valuable habitat for wildlife, even though they are human-created and managed systems.

However, we also found that primary forests support unique compositions of tree and bird species. There were more tree species, and more sensitive and specialist bird species within older forests. This reminds us that, despite the value of agroforests to biodiversity, we should not forget about protecting primary forests. These old-growth forests are especially valuable given that they take hundreds of years to recover following disturbance.

Globally, the proportion of primary forests is declining relative to secondary and planted forests, and our study emphasises the urgent need to protect primary forest habitats and the species they sustain.

A positive message from our research is that young secondary forests, and even actively-managed agroforests, can also support high numbers of bird species, which make an important contribution to biodiversity at the landscape scale. As the proportion of secondary and planted forests rise, these habitats are becoming increasingly important biodiversity reservoirs.

It’s good news for people, too. It shows that agricultural systems like cacao can fit within a human and nature framework by supporting both livelihoods and wildlife.

Farmers of crops like cacao and coffee can choose whether to pursue intensive cacao monoculture in the form of “sun plantations”, or traditionally-managed “shade cacao”. There is evidence that the latter not only supports greater biodiversity, but can also be more profitable in the long-run.

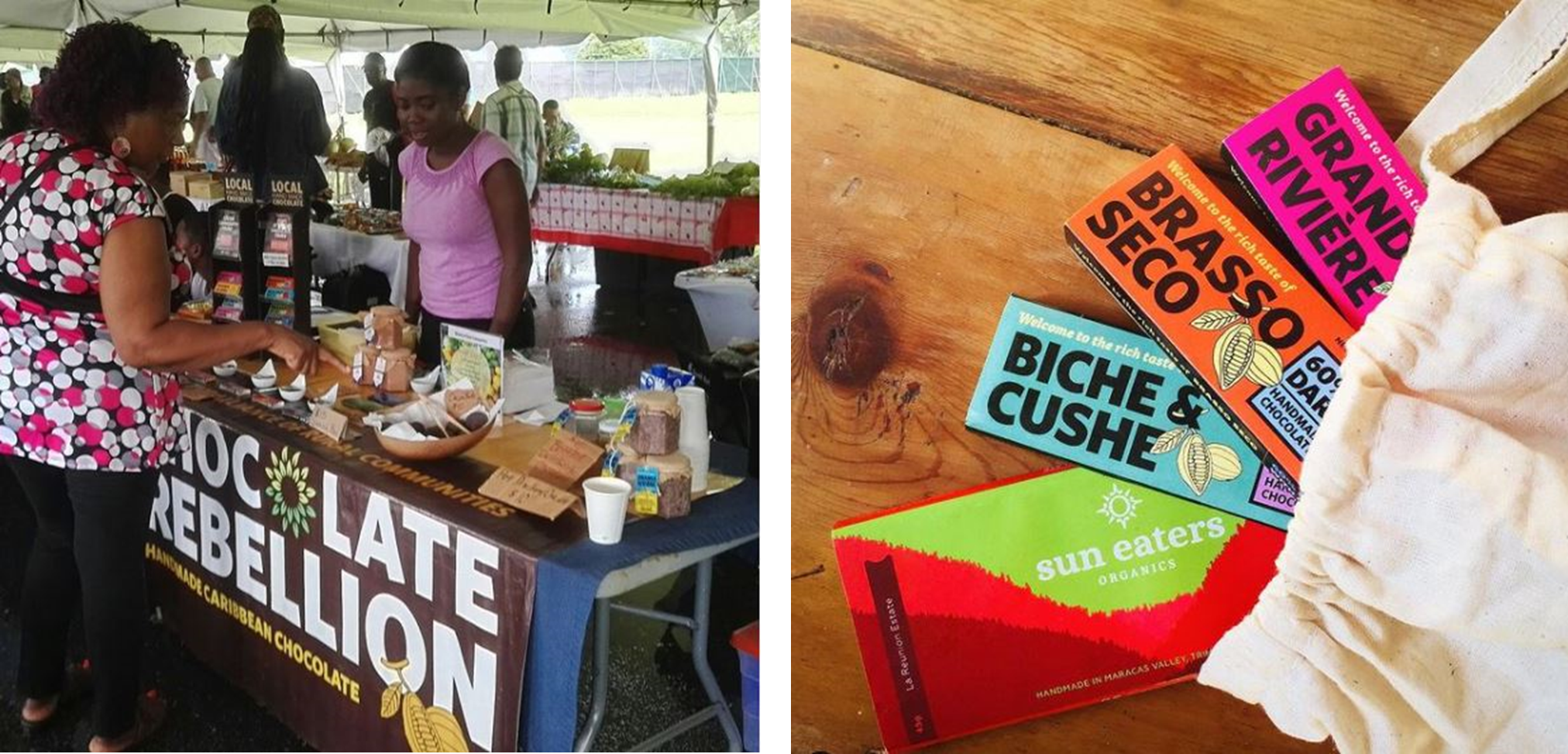

In Trinidad, a growing number of cacao producers such as Brasso Seco, ARC, Sun Eaters and Omarbeans are choosing to grow cacao sustainably as an agroforest crop, and producing bean-to-bar chocolate products to meet a rising local demand for ethically sourced goods.

Our research, alongside the success of these companies, highlights the benefits of growing cacao for people and nature, and showcases a framework which others can follow. It also gives us all yet another reason to purchase and enjoy delicious forest-grown chocolate!

Read the full article Contrasting trends in biodiversity of birds and trees during succession following cacao agroforest abandonment in Journal of Applied Ecology.