Each year, Journal of Applied Ecology awards the Southwood Prize to the best paper in the journal by an author at the start of their career. In this post, Anthony Waddle (University of Melbourne, Australia) discusses his shortlisted paper which developed a vaccine approach for increasing amphibian resistance to chytridiomycosis.

Globalization has allowed us to live comfortable lives, accessing resources that may be naturally scarce in the regions we inhabit. However, although people in a landlocked desert may enjoy a night out eating seafood, moving people and products worldwide has its repercussions; we are currently living in a pandemic which is a product of globalization.

What if I told you that there was another pandemic silently raging, resulting in the collapse of entire species? Well, that’s the jarring reality for amphibians around the world that have been devastated by a disease caused by aquatic fungi colloquially referred to as chytrid (kich-rid).

Thought to be native to Southeast Asia, chytrid has spread worldwide via a variety of possible mechanisms including the trade of amphibians as pets, food, and even as early pregnancy tests. Over 500 amphibian species have declined due to chytrid with 90 of those species being driven to extinction. These numbers characterize chytrid as the worst infectious disease, and among the worst invasive species, in terms of biodiversity loss. The fungus cannot be eradicated in nature and instead many species rely on intensive management for their continued existence.

Translocations are a major conservation tool for establishing or re-establishing populations that have disappeared from the landscape, but unfortunately these tend to have limited success since released amphibians still catch and succumb to chytrid. One potential way to overcome this challenge is to increase amphibian resistance to chytrid through vaccination before release.

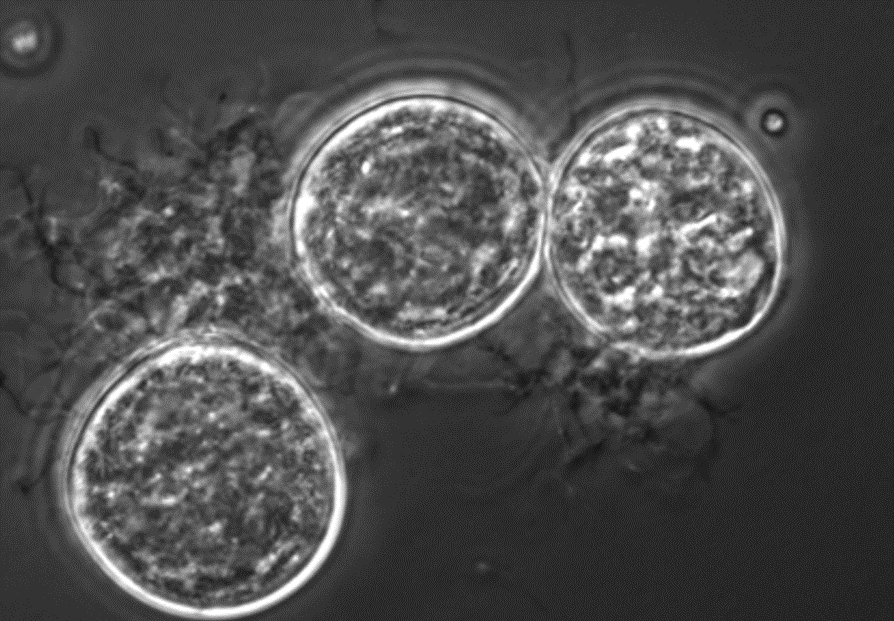

In our study, we successfully tested two approaches for increasing chytrid resistance. First, we tested whether a low virulence strain of chytrid could function as a transmissible, protective inoculum (similar to a transmissible vaccine). We found that the low virulence strain of chytrid easily passed from infected to not infected frogs, did not cause disease, and substantially improved resistance to disease. This is an incredibly exciting result since the development of a transmissible vaccine for chytrid would be uniquely suited for deployment in the wild. Directly vaccinating many wild frogs would be logistically challenging and would require ongoing intervention, but a transmissible vaccine could be administered to a small portion of an amphibian population and spread, propagating the protective benefits, and potentially providing herd immunity.

While the potential for a transmissible vaccine is obvious, there are some risks that need to be assessed before adoption. Therefore, we also assessed a more conservative method of infecting frogs with a strain of chytrid they would encounter at a release site and then curing them before disease developed. This approach had similarly positive results; frogs that had been infected then cured displayed greater resistance to chytrid than frogs with no prior infection. This is lower risk since we clear host infections with antifungals, and the potential for introducing novel strains to the environment is essentially zero since we are using strains that are already present at release sites.

All together these results present the strongest evidence to date that chytrid resistance can be established in frogs that would otherwise be highly susceptible. There are clear management implications to this work that will benefit conservation programs that aim to reintroduce amphibian species to a landscape where they have been extirpated due to chytrid.

Anthony Waddle is a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences at the University of Melbourne, Australia. Anthony’s PhD research uses an interdisciplinary approach to devise conservation interventions that can be deployed in the field to give amphibians the edge over the infamous amphibian-killing chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis). These include developing and optimizing vaccinations against chytridiomycosis, investigating the utility of pathogen refugia for reducing the impacts of chytrid, and building genomic tools to understand the genetic architecture of disease resistance phenotypes. Following his Masters (obtained at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas-UNLV, USA), Anthony moved to Australia for his PhD where he has enjoyed a respite from the scorching heat of the Mojave Desert. You can often find him enjoying the perfect weather of the Australian east Coast, walking through the bush looking for his favorite animals (frogs). His manuscript published in the Journal of Applied Ecology represents a major career milestone and an important foundational paper for developing tools to fight the amphibian chytrid fungus. He thanks his advisors and collaborators in the USA, especially Dr. Jaeger as well as the One Health Research Group of the University of Melbourne for their consistent guidance in getting this project completed. Anthony is finishing his PhD this year and hopes to continue pursuing amphibian conservation research as a postdoctoral scholar.

Read the full paper Amphibian resistance to chytridiomycosis increases following low-virulence chytrid fungal infection or drug-mediated clearance in Journal of Applied Ecology.

Find out more about the Southwood Prize early career researcher award here.