Guest Post by Alyssa Stansfield, 2023-2024 Sustainability Leadership Fellow, and Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Atmospheric Science at Colorado State University

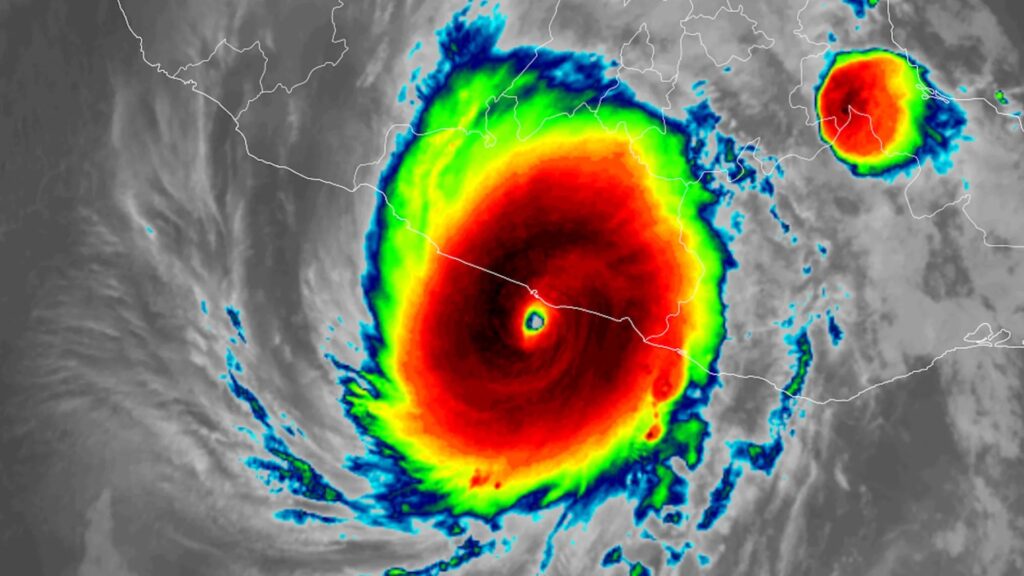

From heat waves sweltering in Brazil [1] to floods wiping out communities in southern Florida [2] to powerful hurricanes devastating Mexico [3], stories about the latest extreme weather events constantly fill our news feeds. If it feels like weather-related natural disasters are occurring more frequently, that’s because they are. In 1980, a weather disaster that cost over $1 billion happened every four months in the United States. In 2023, the U.S. has one of these “billion-dollar events” about every three weeks [4,5]. In the background, the question always looms, “Are these extreme weather events caused by climate change?”.

The link between weather disasters and climate change is complicated. First, it is important to acknowledge that natural disasters are a human phenomena caused by the accumulation of assets (e.g., houses, infrastructure, and vehicles) in areas where extreme weather happens. The number and value of these assets in harm’s way have increased over time, like the growing population near coastlines around the world [6]. As the global population and price of assets continue to grow, the chances of extreme weather causing fatalities, injuries, and economic damage increase.

As society evolves, extreme weather also changes. The increasing greenhouse gases in Earth’s atmosphere are warming the global temperature, shifting precipitation patterns, raising global sea levels, melting glaciers, and more [5]. Climate change is affecting extreme weather as well, but its impact depends on the type of extreme weather event. Heat waves are the most straightforward example. Heat waves are exceptionally hot temperatures lasting two days or more, and as global temperatures continue to rise, this causes hot temperatures to occur more often and last longer. In the U.S.’s largest cities, the average number of heat waves each year has doubled since 1980, which has undoubtedly caused illness, death, and power outages [5].

For other types of extreme weather like hurricanes, the links to climate change are still an active area of research and harder to explain. Scientists will probably never be able to say for certain whether or not anthropogenic climate change caused a specific hurricane to form because we don’t have an “alternate Earth” where humans never started burning large amounts of fossil fuels. Even though we can’t make conclusions about climate change causing a hurricane to form, we can understand how climate change impacts the characteristics of hurricanes. For example, we know that warmer air can hold more water in it and air temperatures have gone up because of climate change; therefore, we can conclude that climate change is causing the rainfall from individual hurricanes to increase [5,7].

While the relationship between climate change and extreme weather events can be difficult to communicate, there is research suggesting that people’s experiences with natural disasters can become “teachable moments” that can catalyze their support of climate action policies and their personal preparations for future disasters [8]. Unfortunately, it is often the most vulnerable people, such as low-income communities, the elderly and disabled, and minorities, who are impacted the most by natural disasters and take longer to recover [9]. We as a society should try to reduce the vulnerability of communities to weather disasters, by taking preventative measures such as providing air-conditioned public gathering spaces during heat waves and incentivizing people to move out of dangerous flood zones. As climate change continues to shift the frequency and characteristics of extreme weather events, we must adapt our preparation and communication strategies.

Additional Resources:

Video from the National Center for Atmospheric Research about how climate change is impacting extreme weather using a baseball analogy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MW3b8jSX7ec

Website of the World Weather Attribution program: https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/

An article from Carbon Brief that explains the IPCC’s conclusions about extreme weather and climate change: https://www.carbonbrief.org/explainer-what-the-new-ipcc-report-says-about-extreme-weather-and-climate-change/

References:

[1] U.S. News and World Report. (2023, November 15). It’s not yet summer in Brazil, but a dangerous heat wave is sweeping the country. https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2023-11-15/its-not-yet-summer-in-brazil-but-dangerous-heat-wave-is-sweeping-the-country

[2] Mckay, R. (2023, November 17). South florida storm dumps more than a foot of rain. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/us/south-florida-storm-dumps-more-than-foot-rain-2023-11-16/

[3] Decavele, J. and Cortes, J. (2023, October 31). 100 dead or missing in Mexico from hurricane, food and water worries persist. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/nearly-100-dead-missing-mexico-hurricane-state-governor-2023-10-30/

[4] NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters (2023). https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/billions/, DOI: 10.25921/stkw-7w73

[5] USGCRP, 2023: Fifth National Climate Assessment. Crimmins, A.R., C.W. Avery, D.R. Easterling, K.E. Kunkel, B.C. Stewart, and T.K. Maycock, Eds. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023

[6] Creel, L. (2003, September 25). Ripple Effects: Population and Coastal Regions. Population Reference Bureau. https://www.prb.org/resources/ripple-effects-population-and-coastal-regions/

[7] Reed, K. A., A. M. Stansfield, M. F. Wehner, and C. M. Zarzycki (2020): Forecasted attribution of the human influence on Hurricane Florence. Science Advances, 6 (1). https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aaw9253

[8] Ettinger, J., P. Walton, J. Painter, S. A. Flocke & F. E.L. Otto (2023): Extreme Weather Events as Teachable Moments: Catalyzing Climate Change Learning and Action Through Conversation, Environmental Communication, 17:7, 828-843, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17524032.2023.2259623

[9] Cutter, S. L., & Finch, C. (2008): Temporal and spatial changes in social vulnerability to natural hazards. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(7), 2301-2306. https://www.pnas.org/doi/abs/10.1073/pnas.0710375105