Guest Post by MJ Riches, 2023-2024 Sustainability Leadership Fellow, and Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Chemistry at Colorado State University

Do Orange Skies Spell Demise?

What was once a display of the peaceful time of day as the sun spills over the horizon is now synonymous with the atmospheric symptoms of wildfires.

The question “why is the sky orange?” peaked on the Google search engine in September 2020, coinciding with the western United States wildfires that, up until this year, set the precedent for wildfire smoke with the greatest impact to US population. A second peak hit Google in June, coinciding with the days surrounding June 7th 2023, the single worst smoke exposure day in United States history, where New York and the surrounding states were drenched in smoke from Canadian wildfires.

Closer to home, skies in Fort Collins rained ash during the 2020 Cameron peak fire. The three largest wildfires in Colorado history (Cameron Peak, East Troublesome, and Pine Gulch) and the most devastating (Marshall) all took place in 2020. By now, orange skies aren’t so alien on the Front Range.

But why is the sky orange? The simple answer is light scattering. Just as small air molecules make the sky blue by scattering blue light at short wavelengths, larger particles like those in smoke scatter light at higher wavelengths and make the sky orange. Determining whether those orange skies spell trouble or time of day requires a bit more context. If you’re curious, you can read about the physics behind light scattering in this Scientific American article. Orange smoke is the same principle as sunsets, but the content of smoke is far more nefarious.

Beyond the Orange Haze

Those orange-scattering particles in smoke are called particulate matter. Scientists divide these up into groups based on size, with the riskiest to health being those under 10 micrometers (PM10) and those under 2.5 micrometers (PM2.5)- for reference the width of human hair is between 50 to 70 micrometers. PM is widely focused on because of the direct health impacts: PM10 is inhaled and reaches the lungs, while PM2.5 can penetrate the lungs and reach the blood stream.

Although the chemical composition of PM varies with the source (even Thanksgiving dinner generates particulate matter!6), PM in general can cause or contribute to health effects including airway irritation, aggravating asthma, lung disease, cancer, and circulatory problems such as irregular heartbeat.

Smoke also carries gaseous compounds that can be harmful to our health, including carbon monoxide, ozone (and ozone precursors called volatile organic compounds), and nitrogen oxides, some of which are carcinogenic.

Ecosystems and the Atmosphere

Human health implications are a primary focus of wildfire smoke related research, but smoke is far reaching, able to travel thousands of miles across the United States and beyond and can linger for weeks to months.

However, as with humans, smoke impacts the health and behavior of wildlife. Researchers have liked wildfire smoke to cardiovascular, reproductive, and activity level changes on wildlife. Many of these changes were induced by changes in habitats like changes in nutrient availability in rain and bodies of water and introduction of toxins into aquatic ecosystems. Smoke scatters light to improve plant photosynthesis, but deposition of smoke chemicals onto plant surfaces can directly harm the plant’s biology. Both smoke and ecosystems are so variable, so the extent of damage is more nuanced than investigating human health impacts.

Take Action

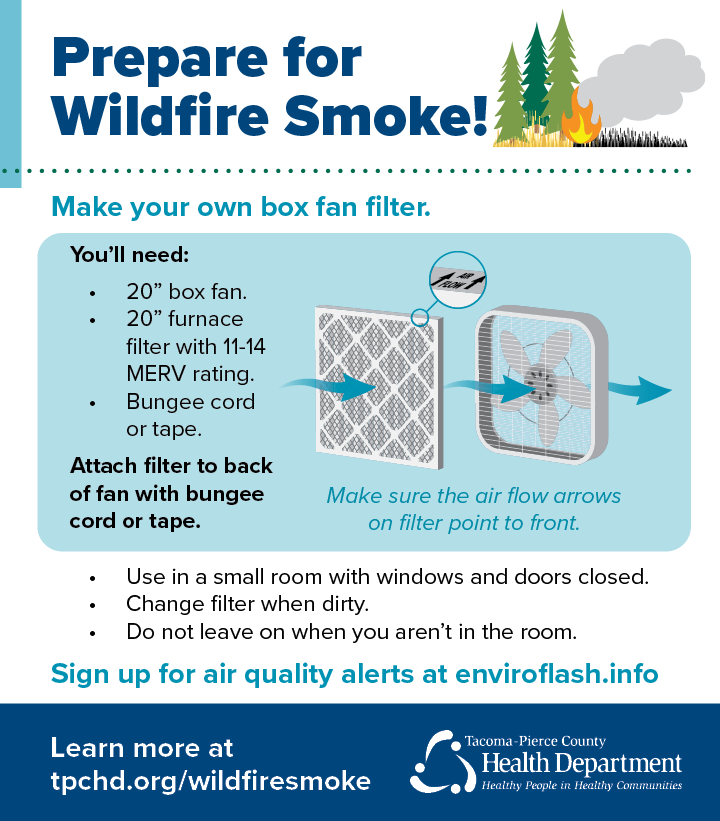

Protect yourself. There are several well-advocated ways to protect yourself from smoke exposure, including: monitoring outdoor air quality, opening windows when air quality is good and closing them when air quality is bad, using face masks outdoors during poor air quality, and using air cleaners indoors. If you don’t have an air filter at home, you can make one using a box fan and an over-the-counter furnace filter. However, scientists are always looking for new ways to reduce smoke exposure. A recent study by Colorado State University scientists Jienan Li and colleagues found that surfaces (like walls, carpets, and furniture) can store smoke compounds. While this initially decreases exposure (by removing those chemicals from the air), these stored chemicals are released once smoke dissipates, thus causing long-term smoke exposure even after the event- lasting up to weeks. They also learned that opening windows post-smoke to improve ventilation and using air cleaners both helped remove those particles, but cleaning surfaces (e.g., via vacuuming) can more effectively reduce indoor smoke exposure. These protective measures are all free or low-cost, yet grossly decrease your exposure to smoke volatile organic compounds indoors.

Inform yourself. There are numerous resources to learn more about preventing wildfires, protecting yourself (and your property), and the science between how and why they spread. The Colorado Department of Public Health & Environment defines air quality and how to identify symptoms of smoke exposure, and they have a site dedicated to general non-smoke air quality including efforts to reduce pollution. The Environmental Protection Agency has a Smoke-Ready Toolbox for Wildfires, which has links for fire weather outlooks, active fire mapping, and health fact sheets. You can monitor the Colorado smoke outlook or national smoke outlook to plan your upcoming outdoor activities.

Support your community. While some may consider becoming a wildland firefighter themselves, there’s many more ways you can support your community. Several agencies collect donations on behalf of firefighter foundations. You can attend festivals dedicated to supporting volunteer fire departments (like the Rist Canyon Mountain Festival), where proceeds go to local departments. On a more intimate scale, you can share your support by writing letters and cards to firefighters and their families.