We are in a critical decade for action on climate change. The world is on track to experience 3°C of warming and the “window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all” is rapidly closing. National governments are the most important systemic actors in the governance of climate action, primarily because they are the only actors with the ability to adopt economy-wide decarbonization measures. However, the vast majority are failing to adopt and implement adequate mitigation policies. States’ inadequate responses to the climate crisis have driven the rise of litigation cases against national and sub-national governments. In this short piece, we take stock of developments in climate litigation against governments, and identify three trends in future litigation – as communities globally keep the pressure on governments to halt further dangerous climate change. Next week’s judgments from the European Court of Human Rights in its first climate cases will be another significant factor to shape this field – so watch this space for more analysis to come!

Stocktake of climate litigation against governments

Over the past decade, communities around the world have turned to the courts to try to hold their governments accountable for failing to act on climate change. ‘Framework’ or ‘systemic’ mitigation cases are those that challenge a government’s overall efforts to mitigate climate change – encompassing both challenges to the ambition of emissions reduction targets and/or their implementation. Over 80 government framework cases have been filed around the world, using a wide variety of legal and factual arguments. This includes, for example, the climate case brought by Korean young people before the Constitutional Court of Korea, which is pictured above. To date, there have been numerous successful cases, including decisions issued by apex courts in the Netherlands, Germany, Ireland, France, Colombia and Nepal.

Researchers have found that successful framework cases against governments have had “a significant impact on government decision-making, forcing governments to develop and implement more ambitious policy responses to climate change.” Governments have been ordered to increase or update their emissions reduction efforts (e.g. Netherlands, Germany and recently Belgium), to clarify their climate plans (e.g. Ireland and United Kingdom), and to implement their existing targets (e.g. France). Reflecting these developments, the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has found that “climate litigation can affect the stringency and ambitiousness of climate governance”.

Outside of the courtroom, high profile litigation can also shift the public debate, driving the narrative that climate action is a legal duty. For example, numerous framework cases against governments have received widespread public support, and encouraged public mobilisation on the urgency of climate action. Over two million people signed a petition to support the French climate case, while nearly 60,000 people joined the Belgian climate case as co-plaintiffs. Success in court in one country can also create international momentum for increased mitigation ambition globally.

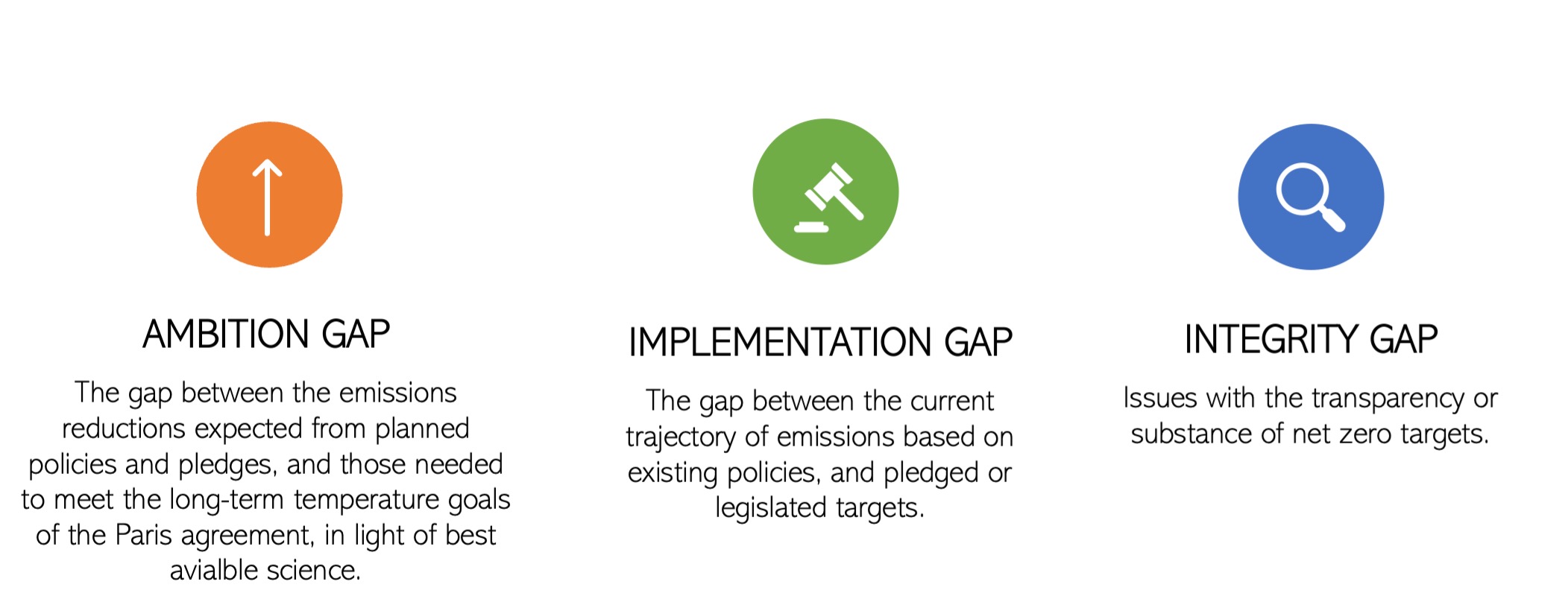

To date, framework climate cases have largely focused on the ambition of governments’ overall mitigation efforts, which we call the Ambition Gap. Here, we define the Ambition Gap as the difference between the emissions reductions expected from a government’s planned policies and pledges, and those required to meet the long-term temperature goals of the Paris Agreement, in light of best available science.

The rationale for this focus on the Ambition Gap is clear – despite the proliferation of net-zero pledges over recent years, governments’ efforts to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions remain “woefully insufficient to meet the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement”. According to the latest UN report, published in November 2023, governments’ 2030 targets would lead to an increase in global emissions of 3% by 2030 – despite the need for global emissions to be slashed by at least 43% by 2030 to keep the 1.5°C temperature target within reach. The gap between countries’ 2030 targets and 1.5°C pathways has remained significant (around 19 GT of CO2 equivalent by 2030) and largely unchanged between 2021 and 2023. In particular, wealthy, high-emitting countries are failing to do their ‘fair share’ of emissions reductions to hold global warming to safe limits.

Out of the successful cases to date, judgments issued in the Netherlands, Germany and in Belgium have required, or caused, the relevant government to increase the ambition of their emissions reduction targets. In the Netherlands and Belgium, the courts found that the relevant government(s) had a duty of care under national law and the European Convention of Human Rights to ensure that emissions reduction targets were sufficient for each country to do ‘its part’ to hold global warming below dangerous levels, in line with best available science. Both governments were ordered to increase their emissions reduction targets to exceed a minimum percentage identified by the courts, based on scientific evidence. In Germany, the Constitutional Court found that the Government had a constitutional duty to ensure that its emissions reduction targets would not lead to future generations being subjected to drastic emissions reductions measures (i.e., due to the carbon budget being used up in earlier years), which would significantly impact their fundamental freedoms. The European Court of Human Rights has been asked to adjudicate in two significant ‘ambition’ cases – one against Switzerland, and another against 33 Member States of the Council of Europe (among others). Communities in Europe and beyond eagerly await the Court’s judgments, which will be announced on 9 April 2024.

Looking ahead at climate litigation against governments

The scale of the remaining Ambition Gap – as the latest UN report underscores – means that litigation is likely to maintain a focus on this area in the coming years. The forthcoming decisions of the European Court of Human Rights in the two cases mentioned above are likely to have a significant impact on the number, and framing, of future Ambition Gap cases – in Europe and beyond.

In terms of emerging trends, there are two key areas of litigation that we anticipate will become more prevalent.

First, the Implementation Gap is becoming an increasingly common – and important – area of focus in framework cases. Recently, many governments have enshrined climate targets in comprehensive or framework climate change legislation – a positive development in climate governance. Unfortunately, in many countries, there remains a significant Implementation Gap between the current trajectory of emissions based on existing policies, and the pledged or legislated targets. At present, governments are off track to implement even their (unambitious) existing emissions reduction targets. Closing the Implementation Gap could make a meaningful contribution to combating climate change. According to UN Environment Program, with current (weak) implementation, policies would lead to around 3°C of warming. Full implementation of commitments under the Paris Agreement would lower this estimate to 2.5°C. Looking out to 2050, fulfilment of all net-zero pledges could limit temperature rise to 2°C.

To date, there have been several successful cases that have sought to force governments to comply with their existing legal obligations – to close the Implementation Gap. Courts in Ireland and the United Kingdom have ordered governments to increase the level of detail in their climate plans, to ensure compliance with national law. Courts in France have also ordered the Government to implement its existing interim carbon budgets and 2030 target, which were set out in legislation. Overall, courts have been willing to engage with questions of compliance with national climate change legislation. For example, this includes the enforcement of existing national targets, as well as other legal requirements concerning the timely adoption of legally required policies and transparency. We anticipate that this will encourage further development and filing of Implementation Gap cases.

Finally, we expect issues related to the Integrity Gap in governments’ net zero targets to gain prominence in future cases. We define the Integrity Gap broadly, to include issues of transparency, as well substantive reliance on carbon dioxide removal (CDR) (e.g., the purpose and nature of use, or the scale of such reliance), in governments’ net zero targets. Most governments are failing to provide clear, ambitious and feasible plans to deliver on their promises – and are therefore lacking a “credible path from 2030 towards the achievement of national net-zero targets”.

One key integrity concern focuses on the lack of transparency and specificity about governments’ proposed reliance on CDR technologies to get to net zero emissions (and beyond). There is a risk that governments are delaying near-term emissions reductions by relying on the future development of CDR. While some governments (such as Germany and Portugal) have adopted CDR targets separate to their emissions reductions targets to address this, the vast majority of countries have not taken this approach.

Wealthy, high-emitting governments appear to be relying on a scale of carbon removal and storage that is far beyond the physical limits of any currently available techniques. Such large scale reliance creates a high risk of future non-deployment, and significant implications for human rights and ecological integrity.

Recently, leading international lawyers and climate scientists published new research that warned that States which over-rely on future CDR to meet Paris Agreement targets could fall foul of international law. The team called for faster cuts in GHG emissions and warned that governments could otherwise risk legal challenges. In the context of these risks, climate lawyers and legal experts have begun exploring legal intervention avenues against over-reliance on CDR, in anticipation of the Integrity Gap becoming a new frontier in climate litigation.

* This piece was originally prepared for a conference on climate litigation in Europe in November 2023 hosted by the Bonavero Institute of Human Rights, University of Oxford.