Why is there a Carrot Boycott in Cuyama Valley?

Small farmers and rural residents are calling for a boycott against Bolthouse and Grimmway Farms. Here’s what it says about California’s effort to manage groundwater.

When California lawmakers enacted the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act in 2014, it was an effort to tame the wild, wild west of water. Nearly a decade later, there’s been some progress creating local sustainability plans, but Big Ag corporations are still hogging water and bullying smaller groundwater users.

Look no further than the fight heating up in the Cuyama Valley, where small farmers and rural residents are calling for a boycott of carrots produced by a pair of big corporate growers who use a lot of water in an increasingly dry place.

The Cuyama Valley sits about 120 miles northwest of Los Angeles, just below the Carrizo Plain National Monument. The Cuyama Basin is entirely groundwater dependent, relying on rainwater to recharge its supply because there are no water delivery canals. And yet this valley boasts an estimated 16,000 acres of irrigated crops: pistachio trees, grape vines, and carrots among them.

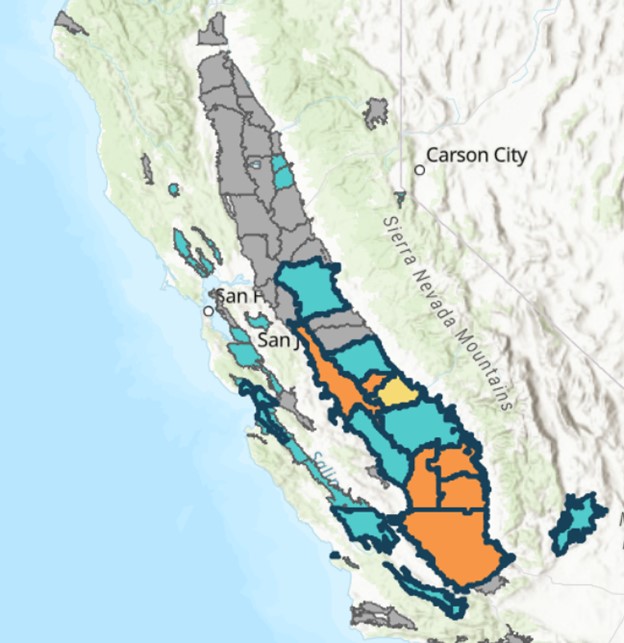

The problem is that more water is being pumped from the ground than is being replenished. Cuyama Valley is one of California’s 21 over-pumped, or “critically overdrafted” basins. These basins are the regions where overhauling water management is most urgent, so they are where the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) is being put to the test first. Under SGMA, local stakeholders must form a groundwater sustainability agency, draft a plan, vote on it, and submit it to the state. Cuyama stakeholders went through that process, but they’ve ended up in court anyway because, as we’ll get into, SGMA doesn’t actually determine who has a right to use the basin’s water—or how much of it.

So, who are these big water users?

Two corporate agriculture behemoths called Bolthouse Farms and Grimmway Farms that grow carrots and other produce. Both are industrial farms owned by private equity firms and headquartered 100 miles away in Bakersfield. Together they produce about 80% of America’s fresh carrots. And they’re accused of being responsible for more than 40% of the Cuyama Valley’s pumping—enough water to supply a large city.

On the other side are the boycott organizers. They are small farmers, farmworkers, generational ranchers, teachers and other Cuyama residents who have started an online petition targeting Bolthouse and Grimmway. They want the two companies to cut the amount of water they’re using and pay more attention to the overall water table among other demands. Some local elected officials support the boycott.

This local fight in Cuyama Valley comes as the overuse of water by industrial farms is gaining attention as a nationwide problem for America’s aquifers. The dispute highlights the limits of California’s landmark groundwater law—especially if you’re not a large corporation. It is also a warning of what may be in store for other over-drafted water basins as climate change makes drought worse and water more precious.

SGMA worked more or less as intended here and the valley still devolved into a nasty battle.

Stakeholders large and small in Cuyama Valley took part in the SGMA process, which requires the formation of a groundwater sustainability agency (GSA) that creates a sustainability plan for the basin. The idea is to encourage local stakeholders to collectively devise a plan for how to reach sustainable water management within 20 years. SGMA does this by focusing on water use, not water rights. And the process was designed to be slow and gradual, presumably to make it more palatable to large landowners. Think of it as the “neighborly approach” to water management. And even though large players can throw their weight around, the public process gives everyone in a community a chance to be heard.

Over the course of about 5 years, the Cuyama Valley Groundwater Sustainability Agency worked to create a sustainability plan for the basin. Representatives of Grimmway and Bolthouse participated; they even sat at the head of the table. After Cuyama’s groundwater sustainability plan was approved by the GSA it was sent to the state’s Department of Water Resources. The state sent it back, identifying several “deficiencies” for correction. The local GSA revised the plan and then voted to resubmit the new version. As the state was approving this revised plan, Bolthouse and Grimmway apparently decided they could get a better deal by going to court. That’s when the two companies initiated a groundwater adjudication action, which is the legal process for defining and determining water rights of all users in a basin. They served most of their neighbors with legal papers.

Jake Furstenfeld is a lifelong Cuyama Valley resident, a cattle ranch foreman, and a member of the standing advisory committee of the GSA. “We are upset that number one we went through the public process, they voted on it, they approved it, and they were a huge part of this whole process—this 1600-page document—and then they went and sued us,” he says. Every groundwater rights owner in Cuyama Valley, including the local school district, is named as a defendant in the joint legal filings in Los Angeles Superior Court. As reported here in detail, the documents ask for a “judgment determining and establishing the rights and priorities of all parties with regard to using and storing groundwater. They request a physical solution, continuous management of the groundwater basin and payment of their legal costs.”

Furstenfeld says he has been inundated with phone calls from longtime residents who had to hire legal representation or risk losing their groundwater rights. He says these concerned residents include employees of the carrot growers themselves, retired folks who are selling belongings to afford a lawyer, and his own family. “We’re spending thousands of dollars that we don’t have on this and it’s literally draining folks. I have limited funds to be able to fund a lawyer… We don’t own land, we don’t own a house, we don’t own anything in Cuyama Valley, any real estate, and we got sued.”

Nicole Furstenfeld, Jake’s wife, is an elementary school teacher and the garden coordinator at the local school. “Now we’re having to spend money on a lawyer to defend our school’s rights to have water and to have a garden for our students.” She says her school—a Title 1 school that struggles to afford the basics—has already paid $26,000 in legal fees.

Bolthouse and Grimmway haven’t said exactly why they decided to go the legal route after the basin had its Groundwater Sustainability Plan in hand. Does the GSP include deeper water cuts than they want to abide by? Do they think they’ll have more control over the legal process than they did over the GSP? Did they always intend to go to court?

In a statement to Bakersfield.com, Bolthouse said it recognizes it has a responsibility to help achieve basin sustainability. “Bolthouse recognizes that the residents of the Cuyama Valley, which include its own employees, have a fundamental right to access clean water and will continue to support that initiative.” Bolthouse also said it expects to see its own pumping volume reduced through the adjudication process, and that “it will abide by the 5%-per-year reductions spelled out by the basin’s new groundwater sustainability plan, at least through next year.” Grimmway told the newspaper that it too will abide by the 5% reduction for at least a year. “By filing the adjudication,” Grimmway wrote, “the parties involved believe it will not only ensure sustainability of the basin but also protect the groundwater rights of all water users, including small pumpers and the Cuyama Community Services District, in accordance with California law.”

Take that with a grain of salt: Here you have two large corporate water users playing a key role in the slow, collaborative process of negotiating an agreement on a groundwater sustainability plan—while they continue pumping groundwater during years of drought. Then at the end of the process once the details have been ironed out, these same players file an adjudication that will take several more years—while continuing to pump water. No small amount, mind you, we’re talking about an annual amount of groundwater large enough to serve the city of Santa Barbara for three years. Voluntarily reducing that amount by 5% for “at least a year” is not the same thing as abiding by an actual groundwater sustainability plan.

So, what are the lessons for the rest of the state, especially for the other critically over-drafted water basins?

It’s a harsh reminder that SGMA was never intended to replace the adjudication process. It is confirmation that corporate water rights holders will vigorously and strategically pursue their interests through both processes. If the SGMA process is the “neighborly approach,” think of the adjudication process as the “nothing personal, it’s just business” approach. That’s because not everyone gets a seat at the table. All parties must get served but some will not be able to advocate for their rights, whether that’s because they can’t afford a lawyer, or because they just don’t show up. And a court decree is more definitive than a GSP. Corporations have plenty of lawyers and they like certainty. This is the calculation of profiteers. Community members in these basins should be aware that the GSP they ultimately submit to the state may help them during adjudication, but it likely won’t prevent one from being filed.

For California policymakers, this shows that there’s much more work to be done to improve the adjudication process for the era of climate change. Corporate water users have more incentives than ever to play hardball over diminishing water resources, but the state has a compelling interest in ensuring sustainability is mandatory, not voluntary. Industrial farms should not be allowed to drain aquifers and threaten the water supplies of their neighbors just because they have used the water for years. Lawmakers should also consider additional ways to level the playing field by providing legal resources for small pumpers who cannot fight for their rights.

For large corporate water users, the lesson here is that their “it’s not personal, it’s business” tactics may radicalize their neighbors, even small farmers and ranchers who are usually the last people to organize politically.

No doubt, the carrot boycott is a David versus Goliath scenario but it’s starting to generate attention. There are some 2,000 residents in the Cuyama Valley. The petition already has three times that amount in signatures—they’ve gathered about 7,000 signatures, though they’ll need a lot more participation to make a dent in the carrot growers’ bottom line. Organizers say they hope people all over the world will pay attention to their Stand with Cuyama campaign, because the customer base that buys these carrots extends from LA to Tokyo. Their products include fresh carrots and baby carrots under the Cal-Organic Farms and Bunny-Luv brands but also fruit and carrot smoothies, all which are sold at Albertsons, Vons and Pavilions, Whole Foods, Sprouts, Walmart, Sam’s Club, Gelson’s, Ralphs, Food4Less, Costco and Target.

Jake Furstenfeld, the cattle rancher, is now one of the organizers urging a boycott of carrots because he sees no other choice. “Don’t buy them for our survival, for our kids’ future,” he says. “If we run out of water here, and they keep pumping the way they’re pumping, we’re all going to have to pack up and leave.” Nicole Furstenfeld has even started giving out carrot seeds to her students to take home. “What we’re encouraging is don’t buy in the store but grow your own,” she says.

Reader Comments

3 Replies to “Why is there a Carrot Boycott in Cuyama Valley?”

Comments are closed.

From the bleachers: “just because they have used the water for years” – so, that’s why they are litigating, yes? You want to take away rights.

This is all the Legislature’s fault. These corporations aren’t dumb – they know whose rights are going to get taken away, if it is left up to politics. Of course they went to court.

From my perspective, I can maybe agree to dislike private equity – or at least, give them mean looks – but even so, I will not look down on a farm just because it is large.

It is the *legislature’s* fault if they didn’t allocate money for everyone to get a seat at the table. (Also, I expect that a judge might be able to fix this, somehow. There’s more than one way to bake a cake.)

I think it’s very shortsighted to pit big growers and small growers against each other. As an eater, I like both groups!

Let’s just find more fresh water from somewhere. If we can make a gas pipeline, why can’t we pipe in water?? Or store more of it. Again … this is *food* you’re talking about.

N is not well informed

Do u need us to sign a petition