Guest Post by Mary Witlacil, 2022-2023 Sustainability Leadership Fellow, and Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Political Science at Colorado State University

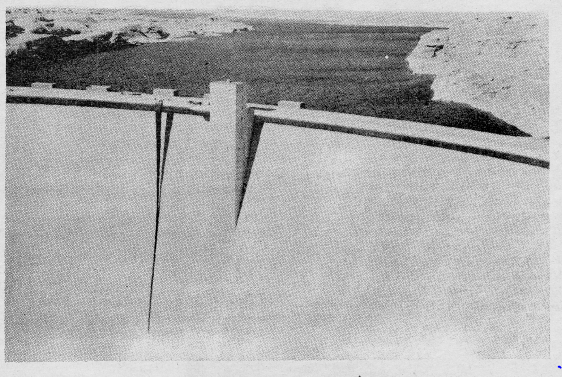

What do a crack on Glen Canyon Dam and a Van Gogh painting covered in tomato soup have in common? They are both acts of pessimistic hope.

With announcements from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) growing bleaker by the year, climate change activism has become increasingly bold and desperate.[1] From members of Extinction Rebellion dumping fake blood on various financial centers, to Just Stop Oil activists lobbing tomato soup on Van Gogh’s painting “Sunflowers,” and Last Generation activists throwing mashed potatoes on Monet’s “Grainstacks” painting, climate change activists seem ever-more willing to face arrest for high-profile stunts designed to stir public response.[2] [3] [4]The desperation of climate activism parallels the rate of loss (and likelihood of climate injustice) predicted by the IPCC and climate scientists, if governments fail to curtail greenhouse gas emissions. Desperate times call for desperate activism, and the greater the loss the bolder the action.

Civil disruption in response to ecological grief is nothing new for environmental activists. Despair over environmental damage and injustice is a uniquely motivating force for environmental activism. Loss, it seems, can be a galvanizing force. Yet, even when faced with widespread evidence of a climate crisis, there is a compulsion to deny that climate change will be as bad as climate models predict. And when things are not that bad, there is no reason to take to the streets. To avoid the agony of perpetual disappointment, we may need to learn how to embrace despair while actively willing social change. Or to put it in Antonio Gramsci’s terms, this moment may call for “pessimism of the intellect [and] optimism of the will”.[5] [6] This approach—which I refer to in a reconstructed manner as pessimistic hope—rejects the collective expectation of passive positivity while creating space for collective action.[7] While despair, pessimism, and grief are often associated with political apathy,[8] pessimistic hope can inspire bold activism and provide an outlet for grief. In this post, I discuss two examples of pessimistic hope: the recent action where Just Stop Oil activists threw tomato soup on a Van Gogh painting, and anti-dam activism on Lake Powell.

Tasteless Food Fight or Creative Resistance?

Few climate change protests have been as fiercely contested as Just Stop Oil’s recent soup stunt. Activists launched a can of tomato soup at Van Gogh’s 1888 painting “Sunflowers,” before gluing themselves to the wall of the National Gallery in London.[9] The point of the protest was not to destroy a work of fine art—which was protected behind glass—but to spark a conversation about the costs of climate change. ““What is worth more, art or life?” one activist yelled.”[10] Toward the end of Cixin Liu’s expansive trilogy, The Three Body Problem, one question posed by Cixin is, what is the value of art on an uninhabitable planet. The Last Generation and Just Stop Oil activists are placing their bodies on the line by asking the same question in real time.

Activism has often been a messy affair, and when grappling with an increasingly dire climate reality, messy and bold action can seem like the only way to grab the public narrative. While their action may have rankled the online community, and alienated would-be supporters, it was bold enough to garner international attention. After the protest, activist Phoebe Plummer explained their actions in a viral video which had 1.7 million views on TikTok and 7.1 million views on Twitter.[11] Attention they sought, and attention they received.

While the media and the public excoriated the activists for attacking fine art, neither Van Gogh’s nor Monet’s paintings suffered any damage. The Van Gogh was returned to the gallery wall the same day as the action, and Monet’s was anticipated to be returned to the wall a few days later.[12] [13] Any time direct action goes viral, it is subject to public contempt for going too far, yet the purpose of such acts is not necessarily to win favor among the public. These acts are meant to challenge the status quo, shift the conversation, and create a temporal disruption that catalyzes massive change, or what Walter Benjamin refers to as “now time.” Beyond declaring that enough is enough, actions like these are acts of catharsis and an effort to awaken those who have grown comfortable with a lack of moral exigency.

It is all too easy to celebrate historic acts of civil disruption only when they have become an acceptable feature of the social and political narrative.[14] Yet, desperate times call for desperate activism. When novel acts of resistance threaten a common sense of decency, it is equally easy to be dismissive of them. In an opinion piece for the Guardian, a backer of the Climate Emergency Fund Acts said “Throwing soup on a beloved painting was a desperate move…Activists are trying everything they can to get our attention.”[15] Direct action is an attempt to reconcile the desire for change with the heartbreak of the “broken down present.” It is an attempt to change the narrative, and by changing the narrative an attempt to change political reality. Desperate acts of civil disruption would be unnecessary if the status quo did not offer such a constrained vision of the future and a limited possibility for change. Their act—a bold action to challenge norms of decorum, and disrupt the status quo despite insurmountable odds, is an act of pessimistic hope. If their movement is successful, I wager their actions will be judged in a more favorable light by future generations. As Phoebe Plummer asked in their viral video, “Are you more concerned about the protection of a painting, or the protection of our planet and people?” Just Stop Oil’s direct action illuminates the painful irony that it would be impossible to enjoy fine art on an inhabitable planet.[16]

Failure and the Glen Canyon Dam

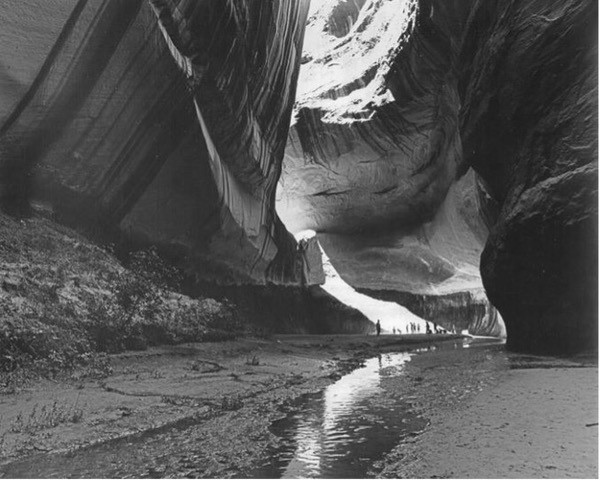

The actions of Just Stop Oil and Last Generation, whether they realize it or not, build on the legacy of civil disruption in defense of the environment. In the 1950s the head of the Sierra Club—David Brower—waged a successful campaign to derail the Bureau of Reclamation’s project of building two dams above Echo Park in Dinosaur National Monument in northwestern Colorado. Unfortunately, this win was short-lived, as it meant flooding Glen Canyon in southwestern Utah for the Bureau’s Colorado River Storage Project. David Brower never fully recovered from this, viewing the loss of Glen Canyon to Lake Powell as a personal failure.[17] Few people who saw Glen Canyon prior to the dam’s construction failed to fall in love with it. “Glen Canyon was”, as Wallace Stegner once stated, “for delight.”[18] The Glen Canyon Dam became an icon of developmental failures and hubris, inspiring generations of environmental activists from Brower and Edward Abbey to Dave Forman, EarthFirst, and contemporary activists like Tim Dechristopher.[19] After the Glen Canyon failure, Brower devoted the rest of his life to saving the wild rivers that he could, and avoided embracing political compromise when it amounted to theft of the natural world.[20]

Now, over fifty years later, with the reservoir (and the Colorado River) consistently experiencing record low flows—experts are hard-pressed to justify why the Bureau of Reclamation flooded the canyon in the first place. It does not directly supply water to any Colorado River users. It is effectively a holding pond for Lake Mead, or as Elizabeth Kolbert puts it, Lake Powell is “a reservoir for a reservoir”.[21] The “Lake” is in the middle of a swelteringly hot desert, so it loses water owing to increasingly dry conditions in the Colorado Rockies, but also due to evaporation. Simply put, the landscape was never meant to store water. In response to why Lake Powell exists, political consultant Matthew Gross has stated “‘You can search and search and search,’…but, if you want to know why Lake Powell was created, ‘you’ll never find a satisfactory answer.’”[22] Flooding Glen Canyon to create Lake Powell was immensely foolish, but the foolishness of this project is not unique. Hubris—when coupled with human ingenuity, and the dual commitments to industrial development and economic growth—has enabled catastrophic environmental degradation the world over. Hubris and environmental destruction, it seems, are necessary complements to economic progress.

Action guided by hope without an expectation of success may result in heartbreak, but it creates space for collective catharsis. In 1981 EarthFirst! unfurled a 300-foot-long banner in the shape of a crack on Glen Canyon Dam, as an act of creative resistance to signify the monolithic injustice of the dam.[23] EarthFirst! activists did not figuratively crack the dam because they expected the dam would come down because of their action. Instead, it was an act of collective catharsis in condemnation of the dam, as well as an articulation of hope for its future demolition. Their figurative crack prefigured the end of the dam. Their action challenged the “broken-down present” and the utilitarian understanding of Colorado River water.[24] It was an act of pessimistic hope, one poised to challenge the status quo without the expectation of a positive outcome.

Conclusion

Lake Powell remains a monument to the climate crisis and a site of perpetual heartbreak. The band that signifies the highest height of the reservoir—aka the “bathtub ring”— is now 30-35 stories higher than the water level.[25] In 2021 drought on the Colorado River was so bad that in June of that year, Utah’s Governor Spencer Cox asked citizens to pray for precipitation.[26] Unfortunately, a commitment to the environment often entails accepting devastating ecological and human losses. Yet, when activism is a mode of collective catharsis whereby activists use civil disruption to express frustration and grief, it has the capacity to sustain their commitment to the environment and climate justice. Pessimistic hope takes action while refusing to ignore the reality of our “broken-down present.” Rather than relying on the passive positivity implied by optimism, pessimistic hope entails a life-affirming approach to the future, but one that is explicitly bound to the present and aware of the catastrophes of the past.[27] An approach that expects nothing but uncertainty but takes bold chances in the present, regardless. By drawing a crack on Glen Canyon Dam or tossing tomato soup and mashed potatoes on fine art—environmental activists bridge the gap between lament and the demand for change. Their political resistance, as well as their unwillingness to deny the gravity of the climate crisis, is something to inspire us all.

[1] United Nations. 2021. “Secretary-General Calls Latest IPCC Climate Report ‘Code Red for Humanity’, Stressing ‘Irrefutable’ Evidence of Human Influence.” UN: Meetings Coverage and Press Releases. August 9, 2021. Accessed Online, October 24, 2022: https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/sgsm20847.doc.htm

[2] Oliver Milman, “Extinction Rebellion protesters pour fake blood over New York’s capitalist bull,” The Guardian, October 7, 2019. Accessed Online, October 24, 2022: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/oct/07/extinction-rebellion-new-york-protest-arrests

[3] Christian Edwards, Duarte Mendonca, “Fossil fuel protesters charged after tomato soup thrown on Van Gogh’s ‘Sunflowers’ in London gallery,” CNN, October 15, 2022. Accessed Online, October 24, 2022: https://www.cnn.com/style/article/oil-protest-van-gogh-sunflower-soup-intl-scli-gbr/index.html

[4] Eduardo Medina, “Climate Activists Throw Mashed Potatoes on Monet Painting,” New York Times, October 23, 2022. Accessed online, October 24, 2022: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/23/arts/claude-monet-mashed-potatoes-climate-activists.html

[5] Antonio Gramsci, Letters from Prison, edited by L. Lawner (New York: Harper & Row, 1973).

[6] Antonio Gramsci often repeated this phrase, but it was originally attributed to French novelist Romain Rolland, in his review of Raymond Lefebvre’s novel Le Sacrifice d’Abraham, in which he describes the task of the intellectual – “Pessimism of intelligence, optimism of the will.” James David Fisher, Romain Rolland and the Politics of the intellectual Engagement. (London: Routledge, 2003).

[7] For a more detailed argument about the political utility of pessimism, please see: Mary E. Witlacil, “The Critical Pessimism of Theodor Adorno,” New Political Science, 44, no. 2 (2022).

[8] Mikkel Krause Frantzen, “Against Pessimism, or, the Education of Hope,” SubStance 49, no. 1 (2020); Wendy Brown, “Resisting Left Melancholy,” Boundary 2, no. 3 (1999).

[9] As of the time of writing, two climate activists engaged in a similar act of civil disobedience, throwing mashed potatoes on to Claude Monet’s “Grainstacks” at a German Museum. See, Medina, “Climate Activists Throw Mashed Potatoes on Monet Painting,” New York Times.

[10] Deborah Vankin, “’Hot would be much worse’: How a priceless Van Gogh survived a tomato soup shower,” Los Angeles Times. October 14, 2022. Accessed online, October 24, 2022: https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2022-10-14/van-gogh-painting-attacked-soup-national-gallery

[11] Karen Ho, “Just Stop Oil Protestor Explains Why They Threw Tomato Soup at Van Gogh In Viral Video,” ART News, October 19, 2022. Accessed online, October 24, 2022: https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/just-stop-oil-protestor-van-gogh-sunflowers-why-video-1234643678/

[12] Ibid.

[13] Medina, “Climate Activists Throw Mashed Potatoes on Monet Painting.”

[14] One need look no further than the mainstream revisionist depiction of Martin Luther King Jr. as the moderate “icon” of the Civil Rights Movement, meanwhile overlooking that he was a democratic socialist. Stephen Joseph Scott, “Martin Luther King Jr. And the Socialist Within, Hampton Think, January 26, 2021. Accessed online, October 24, 2022: https://www.hamptonthink.org/read/martin-luther-king-jr-and-the-socialist-within

[15] Aileen Getty, “I fund climate activism – and I applaud the Van Gogh protest,” The Guardian, October 22, 2022. Accessed Online, October 24, 2022: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/oct/22/just-stop-oil-van-gogh-national-gallery-aileen-getty

[16] Or more likely, it would only be possible to enjoy fine art, if you were wealthy enough to weather the climate crisis without suffering the worst consequences of environmental change. (Pun intended).

[17] Keith Makoto Woodhouse, The Ecocentrists: A History of Radical Environmentalism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2018).

[18] Wallace Stegner, “Glen Canyon Submersus,” In The Norton Book of Nature Writing, eds. Robert Finch and John Elder, (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2002), 505.

[19] In 2008, Dechristopher became a legend in environmental activism, when he acted as a bidder at a public land auction for oil and gas permits in Southern Utah (see “Conclusion” in Woodhouse, The Ecocentrists).

[20] Woodhouse, The Ecocentrists, quoting Brower, 24-25.

[21] Elizabeth Kolbert, “The Lost Canyon Under Lake Powell,” The New Yorker, August 9, 2021. Accessed online, October 24, 2022: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/08/16/the-lost-canyon-under-lake-powell

[22] Ibid., quoting Matthew Gross.

[23] Woodhouse, The Ecocentrists.

[24] Jose Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopias: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, (New York: NYU Press, 2009), 12.

[25] Kolbert, “The Lost Canyon Under Lake Powell.”

[26] Ibid.

[27] This is a vague reference to a quote from Theodor Adorno, “After the catastrophes that have happened, and in view of the catastrophes to come, it would be cynical to say that a plan for a better world is manifested in history and unites it.” Adorno, Negative Dialectics, trans. E.B. Ashton (New York: Continuum Publishing, 1973), 320.