Antarctica’s monster Pine Island Glacier—one of the fastest melting glaciers on the continent—is giving climate scientists new reasons to worry.

The trouble has to do with its ice shelf, a frozen ledge at the edge of the Pine Island Glacier. The ice shelf helps stabilize and contain the vast flow of ice behind it.

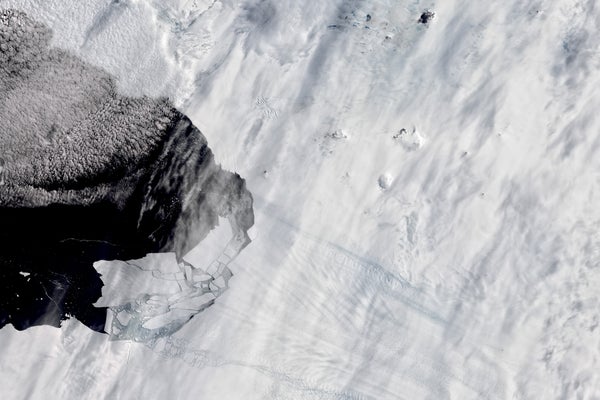

But now it’s crumbling into pieces.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In the last five years alone, more than a fifth of the ice shelf has broken away in the form of gigantic icebergs, which fall into the ocean and drift away.

At the same time, the glacier has begun losing ice at a faster rate. Since 2017, the speed of the ice flowing from the glacier into the sea has accelerated by 12%.

These losses are summarized in a new study, published Friday in the journal Science Advances.

The big question is what will happen next, according to lead study author Ian Joughin, a glaciologist at the University of Washington. There’s a chance the ice shelf may stabilize and the flow of ice will slow down, or at least stop speeding up.

Then again, “the other scenario is this process will continue and the shelf will fall apart far more quickly than we expected,” he told E&E News.

Pine Island Glacier is a mammoth of the Antarctic ice sheet. Studies suggest the glacier, located at the edge of West Antarctica, adjacent to the Amundsen Sea, is pouring nearly 60 billion tons of ice into the ocean each year. Those losses have been speeding up since at least the 1970s.

The ice shelf at the glacier’s edge—a kind of floating ice ledge, jutting out into the sea—is similar to a cork in a bottle, Joughin said. It helps stopper the flow of all the ice pressing against it from behind. The weaker the cork gets, the more ice pours into the ocean, where it contributes to rising global sea levels.

Scientists were already anxious about Pine Island Glacier. The ice shelf had been growing thinner in recent years, melted from the bottom up by warm ocean waters seeping beneath the ice.

This process—warm waters melting the ice from below—has been a growing problem for glaciers along the coast of West Antarctica (Climatewire, April 10, 2018). The water itself appears to be coming from warm currents bubbling up from the deep sea near the Antarctic shore. Experts believe changing wind patterns in the Southern Hemisphere—likely altered in part by climate change—are helping drive these warm currents up to the edge of the ice.

As Pine Island’s ice shelf thinned and weakened, the flow of ice began to speed up in “fits and starts,” according to the researchers. It would accelerate rapidly for a few years, then calm down for a few years. Between 2009 and 2017, the flow of ice was relatively stable.

That changed about five years ago, when the ice shelf began to shed icebergs with greater frequency, some of them several miles long. Last year, the glacier lost a chunk twice the size of Washington, D.C.

The scientists believe uneven speed in the glacier’s flow over the last few decades is at least partly to blame. Over time, cracks and rifts began to appear in the ice. Starting in 2017, the shelf began to rapidly fall apart.

For now, scientists aren’t sure whether the shelf will continue to break apart at the speed it’s been crumbling the last few years. It’s an exceptionally difficult process to simulate in models, Joughin said.

Luckily, satellites are helping scientists keep close tabs on the glacier. The European Space Agency produces new images of the site every six days.

If the shelf continues to disintegrate, it’s possible the flow of ice could speed up more dramatically—perhaps doubling or tripling, Joughin noted. It’s an alarming possibility; Pine Island Glacier already accounts for more than a quarter of Antarctica’s contributions to sea-level rise over the last few decades.

But there’s still too much uncertainty to say how likely that scenario is.

“It’s a little bit of a long shot that the shelf’s gonna fall apart, but it’s not much of a long shot,” Joughin said. “I really hate to make a strong prediction either way which is gonna happen.”

Reprinted from E&E News with permission from POLITICO, LLC. Copyright 2021. E&E News provides essential news for energy and environment professionals.