One of President Biden’s first official acts was to direct his administration to revisit fuel economy and emissions standards set by the previous administration, an urgent act commensurate with the immediate need to get the largest source of global warming emissions in the United States back on track. At first blush, it may look like the administration went big. Unfortunately, the deeper you dig, the more clear it becomes that the proposal released Thursday falls short of that level of urgency.

The proposal released Thursday is unequivocally better than the egregiously bad standards put in place by the previous administration—that is undeniable. But when it comes to what is necessary to address climate change, the hard facts of the proposal show we are only getting part of the way there. Even the administration’s own analysis shows there’s a much better option for the near-term, and if they don’t finalize it, this could limit our ability to address climate change in the long-term by continuing to kick the can down the road.

Could have been a contender

President Biden’s proposal matches the voluntary agreements with California in 2023, an inauspicious starting place. However, the targets ramp up at a rate consistent with the original standards (nearly 5 percent), and by 2026 the targets exceed those of the original 2012 standards, on paper.

But this headline number doesn’t take into account the various loopholes which peck away at the benefits of the rule, and so these top-line numbers can’t tell the bigger story. We’ve already seen reporters mistake this rule as stronger than the standards set back in 2012 under Obama—it doesn’t matter what the rules are on paper but what their effect is in the real world, and here the standards fall well short.

As I’ve iterated repeatedly, loopholes erode the standards by crediting emissions reductions on paper that are incommensurate with what actually occurs on the road. The Obama administration sacrificed roughly 16 percent of the benefits of its standards through 2021 with the various loopholes requested by industry. However, the most egregious of these loopholes were set to expire after 2021. By giving new life to these automaker asks, the Biden administration could be doing even greater damage to its own proposal.

Zombie loopholes

Automakers have asked for a lot of things over the years, and I had thought that we’d finally killed some of these bad ideas under the previous administration. Unfortunately, this proposal brings many of them back from the dead, and made others even worse:

Electric vehicle incentives

I’ve written already about how bad regulatory incentives are for EVs. The Obama administration recognized that at most they could serve a purpose in the very early days of EV deployment—sure, they would erode the short-term benefits of the rule, but maybe it would help jumpstart the industry. State ZEV rules negated much of that potential benefit, but at least they were set to expire in 2021. While the administration has proposed a significantly stronger cap compared to the voluntary California agreements, giving them new life will likely lead to fewer EVs on the road by 2026 than if the administration lets them phase out as originally intended.

Off-cycle credits

Off-cycle credits were supposed to incentive novel technologies that result in real-world reductions. Unfortunately, rather than rein in this program based on the data indicating some of these technologies are not as good as they’re credited for, the proposal actually increases the availability of such credits, putting even more of the benefits of the rule at risk. While clarifications to applicable technologies may result in reduced opportunities for some of the most egregiously overcredited technologies, this does not fix the most fundamental issues with the program and will increase emissions overall by crediting emissions not matched in the real world.

Credit lifetime extension

Generally credits are supposed to last 5 years, long enough to ebb and flow with the automotive product cycle. In the first round of standards, the Obama administration granted a “one-time credit lifetime extension” of up to 10 years, which has led to a significant delay in adoption of more efficient vehicle technologies as manufacturers can just continue to use credits earned early on when the program was exceptionally weak. Now, the Biden administration is turning that one-time thing into a regular practice, extending credit life yet again, which will continue to kick the can down the road as manufacturers use credits to comply rather than sell more efficient vehicles.

Hybrid pick-up truck credits

Another zombie loophole was one that was eliminated during the rollback, appropriately so. The 2012 rule incentivized strong hybrid pick-up trucks as a “game changing technology,” an option now available in the Ford F-150 PowerBoost, with a rather large credit of 20 g/mi. Not only does this credit result in a mountain of credits that don’t yield real world reductions, but forthcoming electric pick-up trucks like the F-150 Lightning and Rivian R1T indicate the fallacy of calling these credits game changing. We can electrify this segment—why incentivize hybrids?

The administration shows a better way

The good, and perhaps perplexing, news in all of this is that the administration actually points to a much better path. Included in the proposal is an alternative (#2) much more consistent with what is needed: it would reinstate the 2012 standards in 2023, and extend them by a year from 2025 to 2026, while eliminating some of the most damaging loopholes. Their own analysis shows that this would be better for the country, with greater benefits, fuel savings, and emissions reductions. And frankly, EPA doesn’t even try to make a good case for why the weaker preferred alternative was chosen compared to this far superior alternative.

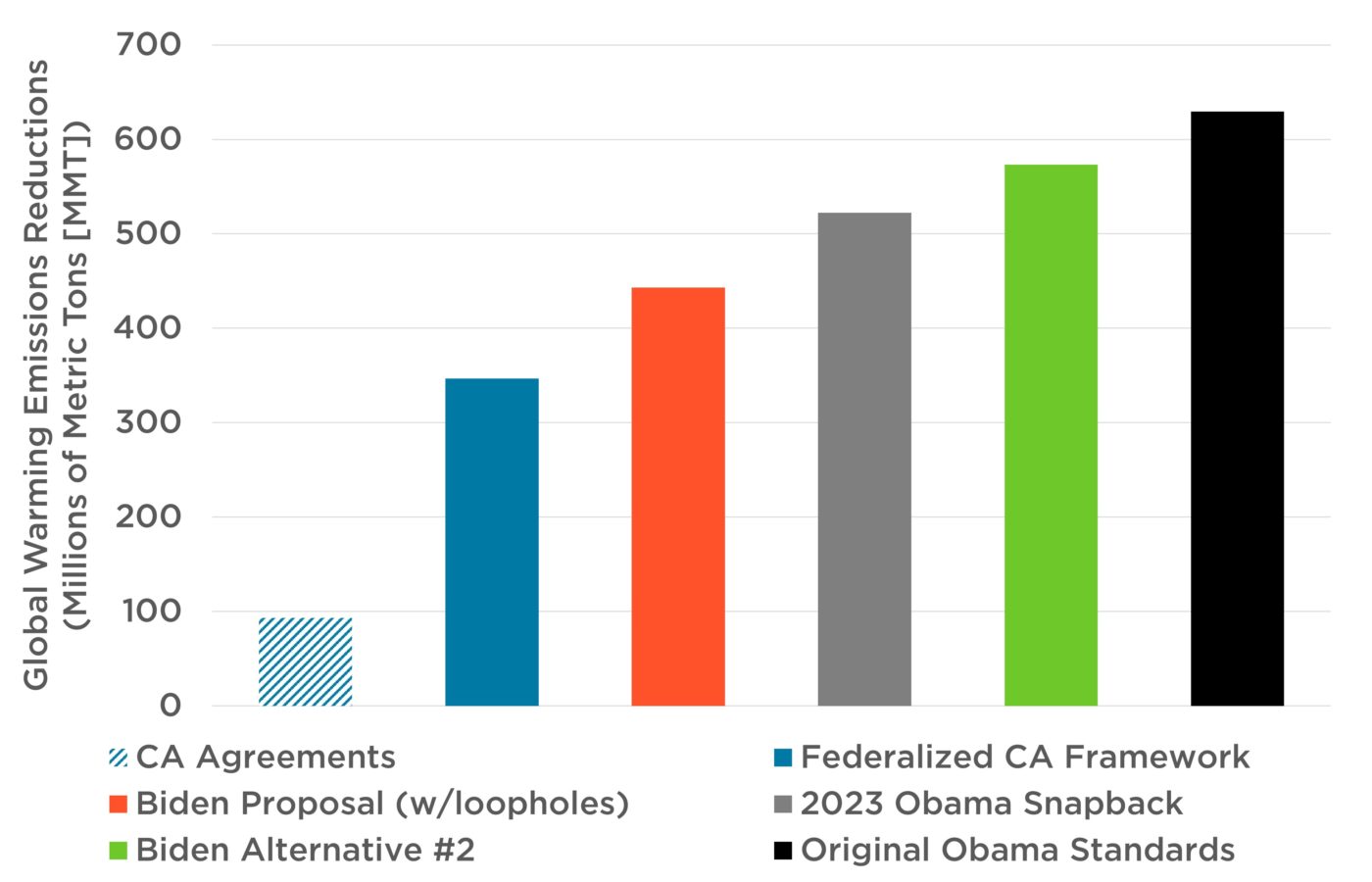

To make it clear just how much weaker the proposal is than what is both achievable and more consistent with the requirements of the Clean Air Act, I thought a “by the numbers” rundown would help put the actual proposal in contrast with what could have been. Here is how the loophole-riddled proposal compares to the administration’s Alternative #2, according to UCS analysis:

- Vehicles sold through 2026 will emit an additional 130 million metric tons of global warming emissions as a result of the loopholes undermining this proposal. In total, the proposal will result in approximately 30 percent fewer emissions reductions than the rule finalized back in 2012.

- By 2026, nearly 400,000 fewer electric vehicles could be on the road by choosing the weaker alternative.

- Fewer efficient vehicles will have a serious impact on the economy: consumers are projected to spend $57 billion more at the pump, with total net social harms of $29 billion (3 percent discount) even after factoring in technology costs, increased vehicle travel, etc. These additional costs are likely to adversely impact jobs economywide as well, with money spent at the pump not being efficiently pumped back into the economy.

Chance for improvement

The numbers are clear: this proposal is not quite enough to put the industry back on track. But there’s still time for the Biden administration to finalize something much better, as I plan on iterating repeatedly throughout the next two months during the public comment period.

Importantly, other aspects of the rule roll-out indicate that at least they have an eye towards the future—for one thing, President Biden issued an Executive Order targeting at least a 50 percent target of new electric vehicle sales by 2030, something that is consistent with what is needed to address climate change. The President also laid out a timeline for dealing not just with emissions from new passenger vehicles, but also for the medium- and heavy-duty vehicles that are at the core of so much inequity in transportation pollution and its disparate health impacts.

But at the end of the day, it isn’t about lofty aspirations or goals—it’s about being able to guarantee we are addressing climate change in a way consistent with the science of what is needed. This proposal could have gotten there—and now we’ve got a little over two months to put it, and the industry, back on track by the Biden administration finalizing something stronger that eliminates all the extra loopholes mucking up the works.