In the run-up to the announcement of the 2021 Nobel Prize for Physics on 5 October, we’re running a series of blog posts looking at previous recipients and what they did after their Nobel prize-winning work. Here Matin Durrani talks to Brian Josephson, who originally made his name with superconductors but has since spent more than 50 years exploring physics and the mind.

With a Nobel prize under your belt and unshackled by the need to “prove” yourself, it must be tempting to set off in new directions – to try your hand at topics beyond the area in which you originally made your name. One Nobel-prize-winning physicist who has perhaps veered off the conventional path more than any other is Brian Josephson, who leads the self-styled Mind-Matter Unification Project at the University of Cambridge in the UK. It aims to understand “from the viewpoint of the theoretical physicist, what may loosely be characterized as intelligent processes in nature, associated with brain function or with some other natural process”.

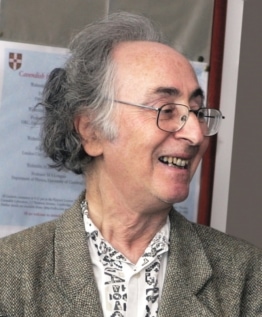

In other words, Josephson, 81, spends his days thinking about how the brain works, investigating topics such as language and consciousness, and pondering the fundamental connections between music and the mind. Most controversially, as far as physicists are concerned, he also carries out speculative research on paranormal phenomena, a field known as parapsychology. Josephson’s interests even touch on homeopathy and cold fusion – two areas in which few physicists would dare to dabble.

But Josephson’s interest in consciousness and the mind is nothing new. In fact, it began long before his Nobel Prize for Physics, which he won in 1973 for work done in the early 1960s during his PhD at the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge. Under the supervision of Brian Pippard, Josephson had predicted that a superconducting current can tunnel through an insulating junction, even when there is no voltage across it, with the current oscillating at a well-defined frequency when a voltage is applied (Phys. Lett. 7 251). Such “Josephson junctions” are central to superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUIDs), which can measure magnetic fields with exquisite sensitivity.

But almost as soon as his PhD was over, Josephson’s attention quickly switched elsewhere. During a year-long postdoc at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, John Bardeen (still the only person ever to have won two Nobel physics prizes) tried to persuade Josephson to continue his work in on superconductivity. Unconvinced, he decided to work instead with Leo Kadanoff on critical phenomena. “But after that I felt that the easier and more interesting aspects of many-body theory had been done and I started trying to understand brain function,” Josephson says.

I felt that the easier and more interesting aspects of many-body theory had been done and I started trying to understand brain function

Brian Josephson

His interests were piqued further after returning to Cambridge, when Josephson got to know the mathematical geneticist George Owen, who in his spare time investigated poltergeist claims. “He talked to me about parapsychology generally and got me interested in that, particularly as I could see parallels between psi phenomena and quantum mechanics,” Josephson recalls. In 1974, shortly after picking up his Nobel prize in Stockholm, Josephson was invited by Owen to a conference on “psychokinesis” in Toronto, where he saw demonstrations of metal bending. “I did some research on this but have always regarded it as a sideline,” Josephson says.

Still, Josephson’s new line of interest was clearly established. He went on to give a course on “creative intelligence” at the Cavendish and even collaborated with Hermann Hauser – the physicist and technology entrepreneur who helped set up Acorn Computers – on a paper on the logic of developmental processes. As the years went by, Josephson began getting invited to conferences concerned with mind processes. “I then started trying to link concepts such as semiosis with quantum physics. Currently I’m working with a quantum physicist who is developing the maths side,” he says.

Looking back on his career, Josephson thinks he would have moved into studying the mind even if he had never received his Nobel prize. “Having tenure would probably have given me freedom to work on it,” he says. Still, despite the prestige that a Nobel brings, life outside the mainstream has not been easy. “The Nobel prize didn’t stop the department being very hostile,” Josephson claims, citing incidences of potential collaborators being discouraged from working with him and having their promised funding withdrawn.

Recognition that mind is fundamental rather than matter will be as significant step for physics as the step from classical to quantum physics.

Brian Josephson

He has also faced criticism from the likes of geneticist David Winter, who have accused him of suffering from “Nobel disease” – the notion that a Nobel prize gives a scientist who is an expert in one area an “unfounded confidence” to speak on subjects they know nothing about. Winter believes the affliction encourages sufferers to “spout anti-scientific rubbish”, citing the Nobel-prize-winning chemist Linus Pauling who thought that high doses of vitamin C are medicinally useful.

Life beyond the Nobel: how Luis Alvarez deduced the disappearance of the dinosaurs

Such comments do not seem to deter Josephson, who believes that, on the contrary, it’s his critics who are in the dark. “It is people such as Winter who speak with unfounded confidence, on subjects they know essentially nothing about such as telepathy, or memory of water,” he insists. “In the latter case, fallacious arguments are frequently used to dismiss the possibility.”

Indeed, Josephson told Physics World he thinks his present work is “much more important than my superconductivity work” even though it has not been finalized. “The point is that recognition that mind is fundamental rather than matter will be as significant step for physics (and for science generally) as the step from classical to quantum physics,” he says. “A number of people have asserted this in the past of course and the question is when we will reach the ‘tipping point’ when ’the club’ will start to take note?”

Physics World‘s Nobel prize coverage is supported by Oxford Instruments Nanoscience, a leading supplier of research tools for the development of quantum technologies, advanced materials and nanoscale devices. Visit nanoscience.oxinst.com to find out more.