The world hosts hundreds of wildly different venomous snake species, from brightly banded coral snakes to camouflaged cottonmouths. But somehow even distantly related species independently evolved specialized fangs with venom-carrying grooves—a longtime puzzle spurring new research into how this could have happened. The answer, says Flinders University herpetologist Alessandro Palci, has been hiding inside the serpents' mouths all along.

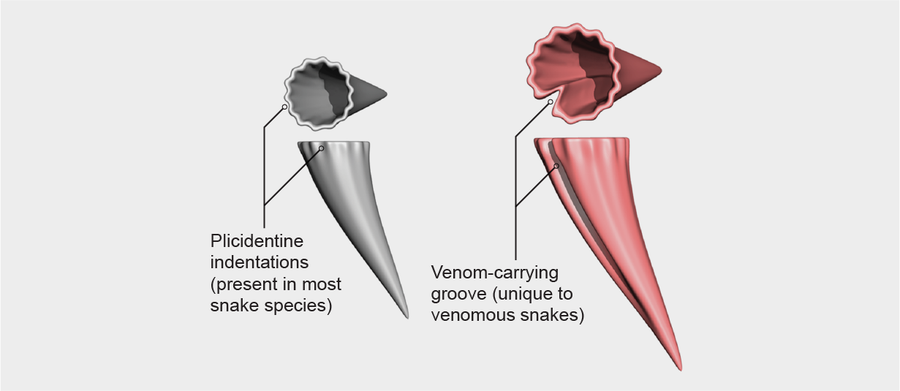

It turns out that the teeth of most snake species, Palci and his co-authors report in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, have a ring of tiny indentations around their bases. This pitted tooth tissue, called plicidentine, helps to anchor the teeth to the jaws. “Before our study, plicidentine was thought to be limited to only three types of lizards among living reptiles,” Palci says. In fact, the study finds, it seems to be ubiquitous in snakes.

Credit: Alessandro Palci, from “Plicidentine and the Repeated Origins of Snake Venom Fangs,” by Alessandro Palci, in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Vol. 288; August 11, 2021

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

And these dental anchors have taken on another function in venomous species, the researchers say. They used microscopic tissue sampling and micro CT scans of snake teeth to determine that in the teeth nearest a snake's venom glands, the plicidentine's folds have evolved into longer grooves that help snake venom flow from gland to tooth—and then into prey.

This result suggests that modern venomous snake species did not have to start from evolutionary scratch every time they developed a deadly bite. Many snakes produce toxic saliva, Palci notes, and a tooth with a more pronounced plicidentine groove lets that incipient venom travel more efficiently. Repeat this change in generations of snakes, and venom-delivering fangs will evolve.

“I love seeing modern imaging technology and beautiful micro CT scans applied to a classic question,” says Whitman College herpetologist Kate Jackson, who was not involved in the new study. Snakes may have developed venom-delivering teeth via other routes as well, Jackson adds. For instance, many fish-eating species have grooved teeth that help to grip slippery prey; these grooves could also have evolved into venom channels. Nevertheless, she says, the study reveals a new common feature of snakes and can inform herpetologists' understanding of how snake fangs evolved anew time and again.