Shahla Farzan: This is Scientific American’s 60-Second Science. I’m Shahla Farzan.

A couple billion years ago—about three billion to be a little more precise—the earth was a very different place. It had vast oceans and almost no oxygen in the atmosphere. It was a place where bacteria ruled.

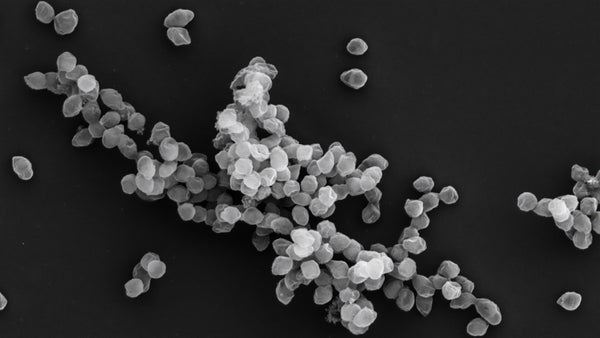

Some of these bacteria used photosynthesis to power themselves, kind of like plants. But they did it in a strange way: by harnessing light and stealing electrons from iron.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Fast-forward about two billion years, and those bacteria still exist today. They’re called photoferrotrophs, and for decades, scientists thought they were pretty rare.

Arpita Bose: Most people think these are exotic organisms that do other things and photoferrotrophy is just something that they might have retained from the past, during early earth history.

Farzan:Arpita Bose is a microbiologist at Washington University in St. Louis.

In 2015, on a whim, Bose collected some vials of marine sediment from Woods Hole, Mass., and brought them home to her lab in Missouri.

Her students slowly parsed out the individual strains of bacteria, and they started testing them, one by one, trying to figure out if any of them still had that ancient metabolism.

Bose still remembers the day two of her students came into her office with the results.

Bose: And they were like, “They all do it. They all do photoferrotrophy.” And I was like, “What?! No way! No way.” I was kind of shocked [laughs].

Farzan: All 15 bacterial strains were photoferrotrophs. Maybe, they started thinking, this trait wasn’t that rare after all.

The study appears in the [ISME Journal]: Multidisciplinary Journal of Microbial Ecology. [Dinesh Gupta et al., Photoferrotrophy and phototrophic extracellular electron uptake is common in the marine anoxygenic phototroph Rhodovulum sulfidophilum]

A big reason why they care—beyond just basic scientific curiosity—is the fact that these microbes are vacuuming up carbon dioxide as they photosynthesize.

Bose: If this is truly as common as our data suggests they are, it’s possible that these organisms do make a massive contribution to carbon dioxide fixation as well.

Farzan: That means preserving the wetlands and estuaries where these bacteria thrive could be an important component of combating climate change.

Right now, those habitats are rapidly disappearing, says Michael Guzman, a microbiologist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and one of the study co-authors.

Guzman: These environments are a hotbed for biological diversity. There’s a lot of things happening in these environments that we still don’t know about. So I think preserving these natural microbial communities is really important.

Farzan: For Scientific American’s 60-Second Science, I’m Shahla Farzan.

[The above text is a transcript of this podcast.]